THE IDEA OF TRANSCENDENCE IS USED TO OBSCURE OPPRESSION

Last week, political advocacy group Catholics for Catholics had an adoration service at Mar-A-Lago in honor of our handsome and strong president Donald Trump. Joseph Strickland was the headliner, Rick Heilman was there, I think John-Henry Westen was there writing about it, Taylor Marshall - hey remember that guy? - was there too, it was a real who’s who of “G.O.T.H.S. subjects from 2020”. Seems like I’ll have no shortage of material to write about in 2025 if this keeps going on, but there’s a huge problem with that: I really cannot make myself care about this event or events like it. I plopped the flyer from the C4C event into the select screen for Mortal Kombat 3, that was kind of funny (kind of), but I just cannot bring myself to learn more about what happened there.

Robert Barron went to the state of the union and posted a video about how mean the Democrats were to our handsome and strong president Donald Trump, but I can’t bring myself to keep paying attention to his bullshit and What It All Means For The Church either, and nothing I write about him is going to top the thing I wrote last year anyways. JD Vance, that guy is apparently (?) still around, and in another world I would do a deep dive into all of the websites that poisoned his brain and title it “Mind of Mencius”, the single greatest title I’ve ever come up with for an essay, but ugh writing that sounds absolutely awful. It is just a shitty, stupid time in our history, and a dangerous and scary time for many, and sitting around writing about my usual bullshit seems like both a tremendous waste of time and a huge bummer for me, and then if I go the other way and just keep writing about David Lynch movies (Fire Walk With Me was very well done but I have no desire to ever watch a movie that pitch-black for a second time1), well, that’s a perfectly good hobby for me to have but that doesn’t seem like anything anyone else would want or need to read.

OFFER VERY LITTLE INFORMATION ABOUT YOURSELF

Here’s a little peek behind the curtain: every single essay I publish on G.O.T.H.S. makes me say “alright, maybe this is the last one”. I’ve permanently ended the newsletter multiple times, and then I keep coming back anyways because I can’t help myself. “Screamland” was the five year mark, that would have been a perfectly good place to end this project for good. “How to be Wrong” would have been a good place to end it. You all really liked “State of Clay”, so much so that I’m still considering just flipping this over into a Moral Orel rewatch newsletter. Maybe that should have been the last one. I’m very grateful that you enjoy reading my stuff, but obviously nobody needs to read my stuff, and obviously I don’t have to write it.

Honestly, this probably won’t be the last essay; like, I’m trying to line up a few more interviews so my pals can plug their books on here, and something stupid will probably happen that piques my interest soon, so you’ll keep getting emails from me. But I mean, come on, this probably should be the last essay, right? Everything is exhausting and idiotic and it feels like each word I try to put down is, you know, not going to be the thing that fixes everything, so why spin my wheels trying to find the right words in the first place. But, as long as I’m putting down words anyways, perhaps it would be helpful if I told you about someone else who once felt exactly like that too, and what they did about it.

THE IDEA OF REVOLUTION IS AN ADOLESCENT FANTASY

In 1932, Dorothy Day was at a loss. She had spent her career to that point reporting on leftist activist movements, and spent a good part of her life participating in those movements herself, and the bad guys had won every single time. The robber barons had stripped the country for everything worth anything, and the masses were left to starve out in the cold. So, by this point, living in America had started to feel very bleak, and Day had basically lost hope in the ability of labor organizing and revolutionary idealism to stop the inexorable tide of rich assholes crushing the poor beneath them, and we know from her writing, notably The Long Loneliness, that she sure as shit didn't think the Catholic church was going to be any help. She had written elsewhere that “I had prayed…that I might find something to do in the social order besides reporting conditions. I wanted to change them, not just report them, but I had lost faith in revolution.” Have you felt all of that yourself recently? It's okay if you have, I certainly have, and Day had, and she was a better person than you or I will likely ever be. Day wrote about her sense of hopelessness, in a political and social environment all pointing to a very bleak future, that “I certainly did not realize at first that I had my answer in Peter Maurin.”

Day lived in a world where everyone was suffering and everyone else was making noise about what caused the suffering and how to stop the suffering. “I had met plenty of radicals in my time and plenty of crackpots, too: people who had blueprints to change the social order were a dime a dozen around Union Square.” But Maurin, a tiny French poet-farmer with a surprisingly complimentary skill set to the battle-scarred labor journalist, was the one who was able to cut through the noise, co-found the Catholic Worker movement with Day, and provide her, and us, with a path forward in a time when everything was falling apart. I figured it was worth looking at what Maurin had to say back in 1932, but first, I want to talk about the noise.

EVERYTHING THAT’S INTERESTING IS NEW

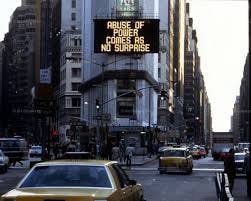

Ohio-born conceptual artist Jenny Holzer was the first American woman to ever have a solo exhibition at the Venice Biennale. You probably have seen some form of Holzer’s work before, even if you don’t go to museums or galleries, because Holzer’s primary medium, for many years, was text, and if you have seen a single sentence IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS presented without any additional context and making a very definitive and borderline ominous statement - whether you saw that on an LED sign or a t-shirt or a website or, as it originally appeared, on a flyer - you probably were looking at part of Truisms, Holzer’s best-known work, created in the late 1970s. That’s where ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE or IT CAN BE HELPFUL TO KEEP GOING NO MATTER WHAT or PRIVATE PROPERTY CREATED CRIME or RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY or A LITTLE KNOWLEDGE CAN GO A LONG WAY all came from you know what if you want to read them all they’re right here.

I should probably clarify, though: these sentences, these Truisms, aren’t things that Jenny Holzer actually believes. I mean, maybe some of them are, I suppose that’s possible, I don’t know. But they certainly can't all be things she believes, because many of the Truisms openly contradict each other. Also, Holzer has been very clear that Truisms are not supposed to all be understood in her voice, but from a wide array of voices that she made up. Her text-based work messes with ideas of voice and authorship all of the time. Living was written on bronze plaques near benches and buildings, as if designating monuments or historical events, except that Holzer’s plaques were really just off-putting second-person instructions on things like “don’t fuck people you hate very often”.

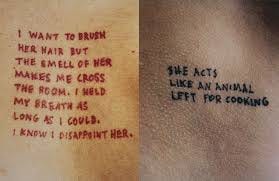

Inflammatory Essays was Holzer doing her best impression of revolutionaries like Mao and Lenin and constructing paragraph-long manifestos to get readers riled up, except the manifestos were all different and, again, contradicted each other.

Lustmord had a stronger narrative structure and described a rape from the perspectives of the perpetrator, victim, and a witness, presented at one time as photographs of the text tattooed on the skin of anonymous models.

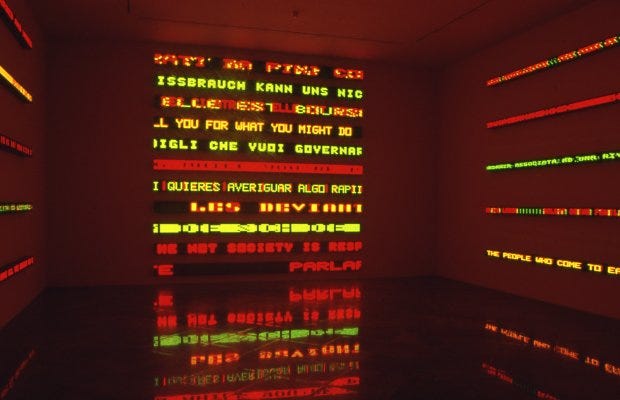

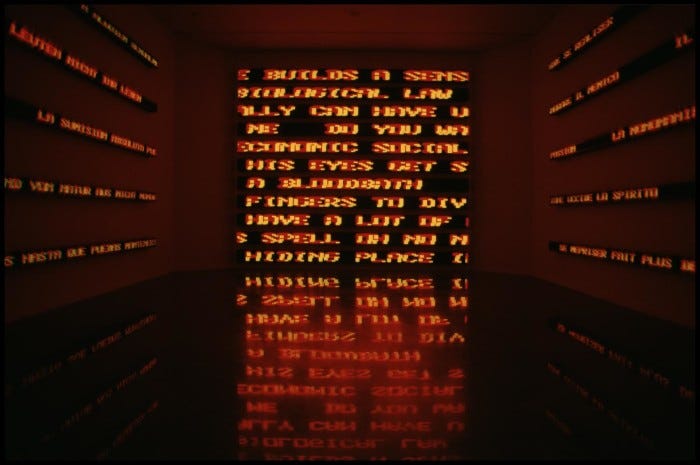

Obviously, Holzer has a deep catalogue of provocative text-based works, texts that make you repeatedly ask “wait who is talking to me now?” But with Truisms, you're hearing from everyone, everyone speaking with absolute certainty and no context or framing. This work is loud. One of the most famous presentations of Truisms, which was included in the Biennale exposition, was a big stack of LED strips just blasting through all of the Truisms in multiple languages nonstop, an installation Holzer referred to as “the toaster” because of the feeling of getting cooked by all of that light:

Holzer played around with different processes and versions of the Truisms concept while a student at RISD and the Whitney. In one telling, she got the idea for Truisms after an exercise copying diagrams out of textbooks, in which she realized that the disembodied captions made for a more interesting piece of art than the diagrams themselves. In another telling, Holzer was attempting to summarize a reading list for one of her classes at the Whitney, to boil each of the books on her list down to one sentence each. What you’re left with, as a person observing Truisms, are bright blaring statements of absolute conviction, and you, instinctively and involuntarily, accept them as self-evidently true. ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE: you just see that on a flyer somewhere, or on a t-shirt, or in the middle of Times Square in the late 1980s:

and you think to yourself “oh, sure, abuse of power comes as no surprise, makes sense, sure.” And then - this is the important part - you’re supposed to go “wait, why do I just assume that makes sense? Wait, why is that on an LED sign in Times Square? That’s not an ad. That’s not a safety warning. Who put that there? Why am I just assuming that’s a true statement? Just because it's on a sign?” YOU ARE A VICTIM OF THE RULES YOU LIVE BY. Perfect, sums up the world as I see it no it doesn’t! It’s made up! Holzer made it up and told us she made it up! The point, of course, is that when you’re surrounded by anonymous voices trying to explain the world to you as quickly and concisely as possible, if explanations of the world become primarily about speed and consumption, it all feels like, well, being cooked in a giant toaster oven. You're supposed to start asking about the truisms you hear all of the time and where they come from and why you swallow them so easily. I’m saying that I don’t think Truisms is going to lose relevance any time soon.

CONFUSING YOURSELF IS A WAY TO STAY HONEST

In early March, Kaya Oakes wrote a great and very short piece expressing an important truth about this era of political writing: everyone needs to shut the hell up, forever:

“Something odd happened during the last Trump administration. People were so distressed by the surprise of the election results that they started looking anywhere to find an explanation for how this had happened, and the place they went looking was often Twitter…This kind of writing, however, is great for the clicks. It gets lots of likes. It gets a ton of engagement. Which is exactly why we all need to stop engaging with it. We all managed to get off Twitter. Now we can make choices about who we read — who has actual expertise, informed opinions, who spends time doing actual investigative work — and who we don’t. The solution to despair is not listening to doom-eager false prophets who want to drag you down while they take your money. The solution is pragmatic. Find your people. Volunteer. Teach. Donate. Make calls. Join a union. Show up. Leave the house. Stop reading this, and get off the internet.”

Oakes was writing specifically about “metajournalists” who just made careers out of posting stuff on Twitter, shooting out truisms like “IT’S TIME FOR SOME GAME THEORY” or “I TOLD YOU SO” or just anything else that wastes everyone’s time. She is not the first person to write that posting will not save the world, but she is the person I needed to write it right now. In 2017 and 2025, there were a lot of people - me included! Sometimes on a website where people just post essays all day! - looking for any one-sentence answers to “how could this happen?” and “what can we do about this?” We were framing everything up all wrong: there’s always been a “This”, and as for what to do about it, well, that answer has been the same for a long time.

THE NEW IS NOTHING BUT A RESTATEMENT OF THE OLD

Okay, yes, the current “This” seems especially bad, I’ll give you that. Last time around, I showed up to a lot of protests and picket lines and teach-ins and took a lot of notes in a lot of socialist meetings in branch library meeting rooms, and today I’m left wondering if labor organizing and revolutionary idealism is going to be enough to stop the inexorable tide of rich assholes crushing the poor beneath them. And that’s the same thing Dorothy Day was wondering in 1932 as the bottom was falling out of the economy and robber barons ran the world and it seemed like the American experiment in democracy was just going to die with a big lame whimper. She decided to get to work helping the poor, the poor who are still there no matter what the state of the American experiment or leftist idealism or revolutionary hope. Another writer I love, Renée Roden, put it like this:

“I find refreshing moral clarity in saints like Dorothy Day who…is not confused about the alignment of the American State and the Gospel of Jesus Christ. While they may occasionally agree on points—and let’s celebrate that—Day did not waste her time on something so fragile, corruptible and inconsequential as the state. She didn’t need to find the Gospel proof text for a specific American belief. She simply got busy with the Gospel: a Gospel that demands every second of our day and every inch of our lives. Choosing the Gospel doesn’t mean that you don’t try to make a more just world or make the lives of your neighbor better, in fact, what it means is that you finally have the right tools for the job.”

You can lose hope, you can drown yourself in the noise, or you can get to work. I’ve learned a lot from Renée’s writing. Renée learned a lot from Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin.

IT’S NOT GOOD TO HOLD TOO MANY ABSOLUTES

The full corpus of Peter Maurin’s written work, the “Easy Essays” that started appearing in the very first issue of the Catholic Worker, may actually total up to fewer words than this essay by itself, which is a brutal indictment of my writing style. In that first issue of the Worker, we have Maurin’s first essay [line breaks sic]:

“If the Catholic Church is not today

the dominant social dynamic force,

it is because Catholic scholars

have failed to blow the dynamite

of the Church.

Catholic scholars

have taken the dynamite of the Church,

have wrapped it up

in nice phraseology,

placed it in an hermetic container

and sat on the lid.

It is about time

to blow the lid off

so the Catholic Church

may again become

the dominant social dynamic force.”

When Maurin and Day met, Maurin showed her an explosive vision - Maurin would have been the first to tell you that it’s not his vision but a vision that has always been part of church teaching - for how Catholics should interact with society and a broken political order. Reading Easy Essays at a time in my life when I feel that every other approach to political or social action that I have ever tried has stalled out, I was awestruck. This work feels like a Grand Unifying Theory Of What I’m Supposed To Do As A Catholic in a way that no other work of theology, except maybe Pascal’s Pensees, has ever felt to me. When I finished reading them, I immediately went back to the first essay and started reading them all again.

I still have critiques of the essays: Maurin loves puns and rhyming turns of phrase so much that he makes me, a guy who loves puns, say “all right buddy, maybe ease up on the puns”. He is critical of Marxism and socialism - he didn’t have a lot of faith in the capacity of the state to set up a social safety net, which would not have been a shocking view in 1932 - but I happen to think those things are Cool and Good. But these essays are, as the name suggests, strikingly simple, and reflect Maurin’s aggressively blunt understanding of Catholicism. For instance: Maurin would see a hungry person on the street in New York. His solution to that person’s hunger would be to give them food. Not donate to charity later in the week, not direct them to an agency, it would be to literally pay his own money to buy that person food and make sure they got fed. As he and Day started helping more New Yorkers and encountering more unhoused people during the Depression, they realized that, well, they were just going to have to start renting apartments nearby so that the people they ran into could have somewhere to sleep. Ignoring or otherwise flaking on those in need was not an option for Day and Maurin; they had gotten to know these people. They had befriended them. You cannot say “sorry man, can’t help you” so easily to someone you’ve gotten to know.

Throughout Easy Essays, Maurin built this “personalist” approach to charity into the three pillars of the Catholic Worker movement. The first pillar is houses of hospitality, the places where they can’t kick you out, and you probably already associated those with the Catholic Worker movement. The second pillar was self-sustaining agrarian communities; Maurin was (rightfully) concerned about the environmental impact of urbanization and, again, didn’t have a lot of faith in the state’s ability to provide food and wanted to make sure communities of Workers knew how to do it themselves. The third pillar was round-table discussions for “clarification of thought”, which I find especially interesting - on the one hand, Maurin knew that the idealistic college grads who came to the Worker would like discussing theory and figuring out how to make the world what it was supposed to be, but the roundtable discussions had another important objective: they kept the idealistic college grads in constant contact with the people that the Worker was serving, and thus kept the idealistic college grads from getting up their own asses:

“We need Round-Table Discussions

to keep training minds from being academic.

We need Round-Table Discussions

to keep untrained minds from being superficial.”

None of the structure of the Catholic Worker or Maurin’s “personalist” approach to helping his neighbor was a substitute for political action; Catholic Workers have always participated in mass action and civil disobedience, and Day kept doing it into her eighties. This isn’t me saying “help people and ignore the news” (although I don’t think that’s a bad way to process the world right now), but rather that any political analysis from a Catholic should be downstream from the daily practice of the works of mercy. Maurin considered his marching orders to come from God, as delivered by God’s direct ambassadors, which is how he referred to the poor (and part of why he chose to be poor himself). The person who said “I need to eat” or “can you help me” or “come on, don’t ignore me”, that person was delivering a message directly from the Almighty. It was not a complicated message, according to the Easy Essays:

“To be our brother’s keeper is what God wants us to do.

To feed the hungry at a personal sacrifice is what God wants us to do.

To clothe the naked at a personal sacrifice is what God wants us to do.

To shelter the homeless at a personal sacrifice is what God wants us to do.

To instruct the ignorant at a personal sacrifice is what God wants us to do.

To serve man for God’s sake is what God wants us to do.”

Maurin only wrote a small body of short essays, presumably because he was busy actually doing these things instead of writing all the time. That’s why Easy Essays works for me, because to Maurin, none of the noise matters, no explanations are needed for how things got this way; in as few words as possible, he lays out what you’re supposed to do and how you’re supposed to do it, in all eras and all times, bleak or not. It is “not a new philosophy but a very old philosophy, a philosophy so old that it looks like new.”

So you get why I’m going to say “alright, maybe this is the last one” after I publish this essay. I can just stop throwing out words and use that time to actually do something, do more, be with the ambassadors of God, be our brother’s keeper, feed the hungry at a personal sacrifice, clothe the naked at a personal sacrifice, shelter the homeless at a personal sacrifice. Why don’t I just do that? Why am I writing this instead of doing that right now? It seriously took me eight drafts to get to a piece that says “we should help people”? All of us throw out words all of the time. A few people found ways to sanctify their words and tie them into action that carried out the orders from God’s direct ambassadors. I think that we should pay close attention to how they did that.

YOU MUST KNOW WHERE YOU STOP AND THE WORLD BEGINS

Another little peek behind the curtain here at G.O.T.H.S.: at the beginning of each calendar year, I jot down a list of things I want to write about, which I then basically forget about and never look at again. I wrote down four ideas for this year, and this one, which in its entirety read “something with Jenny Holzer?” is the only one that’s seen the light of day so far. I like Jenny Holzer and I thought it would be fun to write about her, and I had never read Maurin’s Easy Essays, and he wrote stuff that was supposed to be short and easy to understand, so great, read two things and show the audience that they’re kind of the same, the Speedboat special, I’ve written that essay a couple dozen times and you all usually come with me.

The joke on me, of course, was that the two works pull you in opposite directions. Truisms is about noise, it’s about living in the information age (either the early version of the information age that Holzer lived in during the late seventies, or our stupid version of the information age) and looking for a grand unifying theory of why the world works the way it does, how This could happen, what we’re supposed to do about This now, and how most of the messages we see are just bullshit pretending to provide an answer. All you get from Truisms, by design, is noise, the noise that the entire world is made of now. Easy Essays is also about the noise, and how the noise doesn't matter at all, because it's not hard to figure out what you're actually supposed to do to live the Gospel.

And it's not! Maurin didn't have to write a lot of words to get the point across. Of course, living the Gospel is quite difficult. It's counterintuitive and counterinstinctual. You have to run out and give to the unwanted people in society when every impulse you have tells you to stay inside, to keep you and your family away from anything you don't understand, to hoard your resources for when something unexpected happens. When JD Vance says his Christian faith leads him to take care of himself and his family first, well, even a rattlesnake can do that, but it takes a Christian - and a better Christian than I am, by the way - to act counter to that instinct and run towards the poor and the suffering, to run towards those whom we would ignore out of habit but whom God urges us to see as blessed, to rack up expenses to help them, to learn their names and make it that much harder to avoid helping them ever again.

But as hard as it can be to act in that way, understanding what you're supposed to do isn't that hard at all, is it? When Jesus said “sell everything you have and give it to the poor”, He didn't even bother to use a metaphor or parable. When the rich man ignores Lazarus and tries to beg his way into Heaven, God says “look buddy you knew what you were supposed to do”. The message Jesus gives us, what He commands us to do, is many things - challenging, frustrating, exhausting, discouraging - but I wouldn’t call it confusing. What is remarkable, what Easy Essays drove home for me at the time when I needed it driven home, is that this model for living, this personalist way of looking at the world, this mandate to take care of the poor at our personal expense, stays the same no matter what era you are in. Whether times are good or times are dark, you do it, and we are not the first people to live in dark times. In the final chapter of Loaves and Fishes, thirty years into the life of the Catholic Worker movement, Dorothy Day notes this:

“Thirty years ago people’s main problem was unemployment and the resulting depression. Then the war came, and with it, full employment…we still quoted the Sermon on the Mount; we still spoke of the works of mercy and called attention to the fact that war is inevitably the opposite of them. Laying waste the fields, it brings famine; destroying homes, instead of sheltering the harborless, it drives people even out of their own country. Yes, we still oppose war and the preparations for it. And we are still on the side of the working man. Outwardly, things have changed for him, but ‘prosperity’ and the age of automation have brought the situation almost full circle to what it was in the thirties.”

Times were bleak, and Dorothy Day was at a loss, and she found her answer in Peter Maurin - a man who once said “the truth needs to be restated every twenty years” - and they got to work, and thirty years later, times were bleak in kind of a different way but basically the same way, and the work that needed to be done did not change, so they kept doing it. The work that needs to be done now is no different, no matter how many useless words I jam into this essay. “But there has to be more to it than just that. So many vulnerable people will be crushed by our failing government” they also thought that back then. “The institutional church isn’t doing enough to speak out against obvious injustice” they also thought that back then. “There's a perfectly spherical bishop in Minnesota who spends all day watching bodybuilders on YouTube” they also…there was probably an equivalent back then (Fulton Sheen?). You need to just do something. There are fake truisms blasting all around you from every corner of the internet and the media telling you why This happened and what we're supposed to think about This now and it doesn’t matter, just shut the hell up forever, and do something. The ambassadors of God will certainly show up in front of you whether you seek them out or not: the hungry, the sick, the worker needing to organize, the imprisoned, the sorrowful. Help them at your personal expense. “But times are very dark, will that be enough to change the world?” Lord knows, but I am rapidly coming around to the idea that Maurin’s approach is the only way forward for me. It shows me a path out of the noise. I do not think it is enough to save the entire world. It may be enough to save one person’s world when their world needs saving, and that may be exactly what the Gospel is demanding of me.

I made a joke a few weeks ago about Dilexit Nos and Pope Francis’ repeated attempts to try and simplify his message for a remarkably not-receptive audience (us). I have one last thing to say about that letter: because of the way encyclicals are formatted on the Vatican’s website, the section headers are presented in ALL CAPITAL LETTERS. That’s why I still think about that one header in Dilexit Nos, glaring at me like a Jenny Holzer line, bright and loud and bold and clearly meant to be a self-evident truism, unless it’s not:

THE WORLD CAN CHANGE, BEGINNING WITH THE HEART

This is insane, but my therapist recommended that one to me. I was talking about David Lynch’s death and she was like “oh I remember Fire Walk With Me! That one is great!” And it is, but…