Let's Just Have It A Little Quiet Around Here

My favorite novel and favorite work of Catholic theology are about the same thing: boredom.

"...when invention failed them, they used the fail-safe method for undergraduate work at any solid institution: take two utterly unrelated things or matters and show that they are, if not in fact identical, actually related in the most profound and subtle sense."

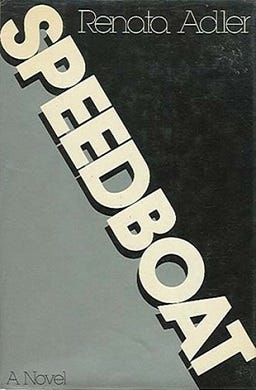

-Renata Adler in Speedboat

"Wouldn't it be nice if everyone would just die?"

-Movie poster tagline for the classic 1997 anime film The End of Evangelion, directed by Hideaki Anno

We’ve really gotten to a point where I’m basically out of ways to make fun of the bishops. So even though they are constantly “at it again”, with, say, Salvatore Cordileone being openly bitter about being passed up for a cardinal-ship, or Joseph Strickland endorsing a Remnant video calling the Pope a “diabolically disoriented clown”, or Robert McManus telling a Catholic high school that they’re not allowed to fly Pride or Black Lives Matter flags, I don’t have an essay’s worth of material in me on each of these incidents. I can come up with a good punny title as always, but that’s about it. For those three, it would be, respectively, “The Spite Album”, “Profane Clown Posse”, and “God Hates Flags”. Still got it.

In all seriousness, I really don't have anything new to say about any of this. If you want to know what I think about what the bishops are up to right now, I think the same things I thought back in earlier pieces: the bishops are old men getting bilked by online grifters. Every bishop is Just Some Guy who will make decisions like the average Just Some Guy you know. The laity, particularly lay employees of dioceses, have the ability to materially and meaningfully pressure bishops to act differently. I still think all of that is true.

But even though I and many other, much more thoughtful writers have written about what stuff like this means for Catholicism, for the episcopate's place in the culture wars, for white nationalism's influence on the Catholic church, I don't think enough people - including me - have been asking this critical question: do the bishops just not have enough to do?

I don't mean "wow why were Cordileone or Strickland or McManus doing all of this instead of serving the poor, that’s not very Catholic of them", although that’s also a very valid point. But I'm actually asking about, like, the on-paper job of being a bishop, the thing they all clock in for, which, as I understand it, is supposed to be a demanding job. If you’re a bishop, you oversee organizations that include dozens, if not hundreds, of employees, and are ultimately responsible for how those employees are organized and compensated. You are directly responsible for what is likely the largest network of private schools in your city or cities, including curriculum, staffing, and organizational structure. You are directly responsible for what is likely the largest network of private social service providers in your city or cities, again including staffing and structure and allocation of resources. You are directly responsible for the training and spiritual formation of the priests in your employment, including staffing and resourcing a diocesan seminary. You are directly responsible for the finances of an institution that famously has very bad finances, often requiring unpleasant decisions on layoffs, consolidations, closures, and out-of-court settlements. You are directly responsible for implementing policies and procedures to police and investigate sexual abuse allegations that surface on your watch. You have to travel and go to meetings and put out statements and collaborate on teaching documents and pastoral letters. So yeah, I think these guys suck, and I do think the Vatican should transfer them all to remote posts in Alaska like Jude Law did in that one TV show, but I also have to ask: what is any bishop doing watching right-wing YouTube videos or telling schools to take down a flag because it’s “anti-police” or being mad at another bishop for getting promoted? How do they even have time to do any of that? Why do they seem to think their jobs require them to make time for that?

This is an essay about what we do when we get bored.

Even though boredom is about as close as you get to a universal human experience, it's pretty hard to write about, as you'd expect. It's not that easy to say something about nothing happening. I think that's why, when a New Yorker journalist wrote her debut novel about boredom in 1976, it picked up a cult following that is still around today, because this author had done something that everyone knew was very universally resonant but still very difficult.

Renata Adler’s Speedboat is one of my all-time favorite novels, and I really do think it is spiky and brilliant and moving and hilarious, but it’s going to be a little hard for me to describe what happens in the novel. Speedboat is, I think, about a writer named Jen who lives in 1970s New York - I think - with people whom I think are her friends. They have too much money and their jobs have too much prestige and they sound insufferable, and you get the impression throughout Adler’s short novel that they’re just all kind of trying to waste as much time as possible, waiting for some better, next chapter of their life after “young rich shithead in Manhattan” that’s never going to start.

I used a lot of “I think”s up there because it’s very difficult, on your first pass through Speedboat, to actually figure out who the main characters are - I’m not even a hundred percent sure that anyone calls the narrator “Jen” in the actual text of the novel - or what happens to them, or in what order those things happen. Speedboat is infamous for its ultra-modern rejection of traditional narrative structure: the novel is told in short paragraphs that shift rapidly between settings and characters, seemingly at random, leaving the reader scrambling on all fours across every stretch of blank page to figure out how this all hangs together. Those paragraphs, in turn, are grouped into chapters, which appear to be named and collected arbitrarily. Most of the characters don't have names, and the ones that do aren't referred to by name very often, so you can't really keep anyone straight. There are very clear themes which recur with some regularity throughout these paragraphs, and the rate of recurrence accelerates as the novel goes on, but you are still shoved from idea to idea with no linear narrative to connect them; it’s a novel that does a very good job simulating the feeling of having a migraine headache screaming inside of you while you try to fall asleep, and the novel appears to be deliberately structured that way to reflect the fragmented and aimless lives of Jen and her friends.

One of the recurring themes, because this is a modernist novel from the seventies, is the nature of narratives in general, and what happens in our lives when we aren't able to find a narrative structure for our day-to-day activities. Jen at one point notes that “The whole magic of a plot requires that somebody be impeded from getting something over with." Towards the end of the novel, Jen gets a little more explicit:

“I had begun to believe that a story line was a conceit like any other…the plot of things converging…the plot of things separating, not so common, disintegration, breaking up. The plot of one thing following in the track of another, as in thrillers, chases. The plot of things parallel. Suspense, which has time as an obstacle to a resolution in the future. Nostalgia, which has time as an obstacle to a resolution in the past. Maybe there are stories, even, like solitaire or canasta; they are shuffled and dealt, then they do or they do not come out. Or the deck falls on the floor.”

This isn’t a particularly subtle passage to put near the end of your extremely fragmented first novel. You just flipped your way through Renata Adler’s solitaire deck, and now we all have to figure out if the stories come out in any meaningful way.

Speedboat had an outsized influence on modern literature for a book that was out of print for decades. Famously, David Foster Wallace taught the novel to his classes at Pomona College, and it's easy to see Adler's influence on his work1. Adler's novel now has a dedicated cult following and an influence across literature from the second half of the twentieth century - and the first few decades of this one - felt in any work of fiction with a deliberately fragmented, head-whipping structure meant to detach the reader from a traditional plot arc. Speedboat was one of the first and best to do this.

Speedboat is also very influential in modern literature because, as with many works of modern literature, all of Speedboat’s characters are bored and miserable all of the time.

It’s a natural impulse to try and impose some sort of narrative structure on your life, to kind of help things make sense. Things happen one after the other, and there are clear causes and effects for events, and the things that people say clearly and appropriately reflect the ideas that they are trying to communicate, and when people interact with each other, it’s because they’re trying to accomplish something or because they like spending time with each other. Those are all things we take away when we read and watch narrative fiction. And then when you read a novel like Speedboat, which deliberately deprives you of all of that, you start to pretty quickly re-think the narrative structure you have tried to overlay on your life. You start to think that maybe fewer of your interactions than you’d prefer have been motivated by “because we like spending time with each other” and are maybe more just something each of you are doing to pass the time:

"I often meet people who do not like me or each other. It doesn’t always matter. I keep on smiling, talking."

And maybe you haven’t really been talking about the Big Ideas or the Issues Of The Day with these people because none of you can correctly translate what’s in your brain into what’s supposed to come out of your mouth, and you’re starting to worry that you just don’t possess the capacity to say anything important to anyone at all:

"He’s doing a political essay. It begins, “Some things cannot be said too often, and some can.” That’s all he’s got so far."

Maybe you and everyone around you are all trying to talk to each other and delivering your lines “almost with passion”, without ever really being able to unlock yourself and be your true self to others:

"“I can’t believe it,” people said, almost with passion. It was that year’s version of hello."

Maybe you’re not the main character of the story of your life, and worse still, maybe the story of your life isn’t actually about your life at all, and also that story doesn’t make any narrative sense in the first place. You try some things to make it better and sometimes they work and sometimes they don’t:

"For the severely depressed, the paranoids, and the hallucinators, our young psychiatrists prescribed “mood elevators,” pills that were neither uppers nor downers but which affected the bloodstream in such a way that within three to five weeks many sad outpatients became very cheerful, and several saints and historical figures became again Midwestern graduate students under tolerable stress."

Feeling that your life is not attached to a recognizable narrative structure, that you are not a saint or a historical figure, can be unpleasant. You scramble through all of the interactions in your life and second-guess yourself and you feel a lot of regret and embarrassment and dread. And then that all feels more unpleasant when you start to realize that it’s possible, and maybe even likely, that everybody else around you is dealing with this too. Maybe there’s absolutely nobody in the world - not in your job, not in your family, not in the government, not in your church - who has any idea what they’re doing, or how to actually get the stuff that’s in their brains across to the brains of other people. Maybe every single person you’ve ever met is actually a minor character, and none of our stories make sense, and the deck is about to fall onto the floor, and there are some occasional flashes of insight, but it’s never going to amount to any sort of redemptive storyline. And you start to feel this horror that life was fun once but now seems to be nothing but boredom because there’s no longer anything to aim for, any sort of narrative arc to attach yourself to, and the best you can do is unsuccessfully distract yourself as you barrel towards oblivion, illustrated very viscerally with this anecdote that gave Speedboat its name:

"And then, at speed, the boat, at its own angle to the sea, began to hit each wave with flat, hard, jarring thuds, like the heel of a hand against a tabletop. As it slammed along, the Italians sat, ever more low and loose, on their hard seats, while the American lady, in her eagerness, began to bounce with anticipation over every little wave. The boat scudded hard; she exaggerated every happy bounce. Until she broke her back."

Everyone in your life, as reflected by Speedboat, is just some idiot barely holding it together and if our stories fit together in any meaningful narrative way, we sure as shit can’t see it from where we’re standing, and we're just going to continue doing stupid things to distract ourselves until reality hits us. And once reality hits us, we're going to have a choice to make.

There aren't a lot of works of Catholic theology that are anything like Speedboat. As I understood it, especially at my Jesuit high school and as I began studying theology in college, Catholicism was all about understanding that you were part of a big, beautiful, moving story of salvation history, that you were in the middle of a story written by Christ that had a beginning, middle, and end. Everything was connected and everything mattered. Catholicism was all about a sacramental worldview, looking at the things that happened in our lives and understanding that they were communicators of God’s grace. Catholicism was about going through the world knowing what you were actually doing, and that knowing that the things you did, the things you said, the people you met, had meaning as part of a larger story of salvation. There aren't a lot of works of Catholic theology that present life the same way that Speedboat does, that are also infamously fragmented in structure, and explicitly dedicated to the idea that we’re all just wandering around with no idea what we’re supposed to be doing, trying - mostly unsuccessfully - to distract ourselves from the boredom and meaninglessness that’s trying to swallow us whole. There really aren't a lot of works of Catholic theology that sound anything like that.

But there is one.

Blaise Pascal is my favorite theologian of all time. It's not close. I still vividly remember the lecture on Pascal’s Pensées in my “Christian Theological Traditions II” class, which we theology students all called “Trads II” because it was a different time (2007) before “trads” meant “people on Twitter who never learned how to masturbate.”

Blaise Pascal was a 17th century Catholic theologian, and Pensées is his collection of basically all of his leftover notes on Catholicism, published posthumously and in fragments. Pensées is laid out in short numbered paragraphs, some of them related, some of them not, some of them grouped together, seemingly arbitrarily, and depending on which translation or edition of Pensées you read, the paragraphs will be in a different order. And, depending on which commentary on Pensées you read, the paragraphs will be in the wrong order. So, you read through analysis of the prophetic books of the Bible, and various proofs of Jesus's divinity, and then also weird stand-alone non-sequitur musings like "Cleopatra's nose: had it been shorter, the whole aspect of the world would have been altered", and you're left to wonder how it all hangs together.

But my college lecture on Pensées didn't cover any of that, and it didn't cover Pascal's Wager, although that is in the same book and is easily Pascal's most famous contribution to theology. Instead, my professor talked about misery, boredom, and diversion. Those three things, according to Pascal, pretty much cover the entirety of human experience throughout history.

Pascal came by this view honestly: in one short period of the early 1650s, his father died, his sister left the family to enter a convent, and Pascal himself almost died in a carriage accident. He lost his entire close-knit support system, and he almost lost his own life. Existence was random and absurd and could end at any second.

To state the obvious, this is also true of you and me, and we've lived through a plague for the past few years (years!) so it's really been right in front of our faces in a very new way recently: you, and the people you love, could die at any second, for no good or predictable reason, and there's nothing we can really do to prevent that. How can you possibly live your life with such horrifying knowledge? You probably use the same approach that I use every day, that Pascal and Adler both wrote about at length, the one thing we all do to fight our our way through life daily while facing this brutal and paralyzing reality:

We just, you know, kind of try not to think about it very much.

That's what a large part of the Penseés is about: diversion, which is basically the center of all of our lives:

“Death is easier to bear without thinking of it, than is the thought of death without peril…As men are not able to fight against death, misery, ignorance, they have taken it into their heads, in order to be happy, not to think of them at all."

Pascal argues that this is true, all the time, of everyone. It's true of you and me right now. The past few weeks have not been an especially encouraging time to be a person in America, and there have been several very big waves of very bad news recently. Rights are being taken away, our government is on the verge of falling apart, there are multiple mass shootings every day, Kendrick Lamar made an album about cancel culture. Have you made sure to carve out a lot of time to sit alone, by yourself, in silence, to just think about how horrifying everything is and how you are powerless to change it as an individual? Or are you like most people who are looking for things to take your mind off of that stuff?

“Nothing is so insufferable to man as to be completely at rest, without passions, without business, without diversion, without study. He then feels his nothingness, his forlornness, his insufficiency, his dependence, his weakness, his emptiness. There will immediately arise from the depth of his heart weariness, gloom, sadness, fretfulness, vexation, despair…Thus they are given cares and business which make them bustle about from break of day.— It is, you will exclaim, a strange way to make them happy! What more could be done to make them miserable?— Indeed! what could be done? We should only have to relieve them from all these cares; for then they would see themselves: they would reflect on what they are, whence they came, whither they go, and thus we cannot employ and divert them too much.”

This is central to Pascal’s understanding of theology, sociology, history, everything. Nobody escapes this. With no distractions, you would have no choice but to contemplate the absurd random viciousness of the world, and our powerlessness to change it, and that’s too horrifying for us to want to comprehend. So diversion, happiness through distraction, is what we all unanimously picked instead.

“I have discovered that all the unhappiness of men arises from one single fact, that they cannot stay quietly in their own chamber…so wretched is man that he would weary even without any cause for weariness from the peculiar state of his disposition; and so frivolous is he, that, though full of a thousand reasons for weariness, the least thing, such as playing billiards or hitting a ball, is sufficient to amuse him…take away diversion, and you will see them dried up with weariness. They feel then their nothingness without knowing it; for it is indeed to be unhappy to be in insufferable sadness as soon as we are reduced to thinking of self, and have no diversion."

I mean, you can try for material gains, to improve your status and position in the world, and that might make you happier. But it probably won’t:

"The king is surrounded by persons whose only thought is to divert the king, and to prevent his thinking of self. For he is unhappy, king though he be, if he think of himself. This is all that men have been able to discover to make themselves happy."

Pensées is a book of Catholic theology that doesn’t really spend any time talking about the liturgy, or Catholic ritual at all, or the church fathers, or the theologians who came before Pascal. Long stretches of the book pass by without any references to scripture. The book doesn’t talk about grace or beauty that we find in nature leading us to God. It doesn’t talk about the church hierarchy and the values of consecrated life. It talks about us being so scared of the brutal violent world, and of our own mortality and impotence, that all of our lives are spent desperately trying to think of anything else so we don’t end up paralyzed. In his words, "we run carelessly to the precipice, after we have put something before us to prevent us seeing it."

But we can't do this indefinitely. The longer we ride in the speedboat, the greater the chance we have of finally hitting a bump and breaking our backs. Reality is eventually going to hit us, the reality that we are each an unnamed minor character that is not steering the plot of the world and that could be taken out of the story at any time. And once reality hits us, we're going to have a choice to make.

The first summary I heard of Pascal’s Wager was over-simplified and went like this: the Wager is basically that you might as well believe in God and try to get to Heaven, because if you live your life believing in God and it turns out, at the end of your life, that God doesn’t exist, you probably didn’t lose all that much. And if you live your life not believing in God and it turns out, at the end of your life, that God does exist, you’re fucked. That’s not what the Wager actually is, and it’s also not exactly airtight in its logic; for example, if you die and meet God and say “I believed in you because it presented the lowest calculated risk to my soul”, I feel that God would be unlikely to be impressed with your piety. Terry Pratchett even riffed on this idea in his fantasy novel Hogfather:

“...this is very similar to the suggestion put forth by the Quirmian philosopher Ventre, who said ‘Possibly the gods exist, and possibly they do not. So why not believe in them in any case? If it’s all true you’ll go to a lovely place when you die, and if it isn’t then you’ve lost nothing, right?’ When he died he woke up in a circle of gods holding nasty-looking sticks and one of them said, ‘We’re going to show you what we think of Mr. Clever Dick in these parts…’”

That’s not what Pascal is really saying, and presumably when he died, God did not call him “Mr. Clever Dick” (although, if you're familiar with Pascal's other works like the Provincial Letters, you might think that nickname would suit him). Pascal does lay out that, logically, yes, the potential risk of not believing in God and potential reward of believing in God makes the question of belief look pretty simple.

But the Wager is not about your best chance to enjoy the afterlife, it's about your best chance to be an alive person in the world who is not going insane. Here's how Pascal puts it:

"We must live differently in the world, according to these different assumptions: (1) that we could always remain in it; (2) that it is certain that we shall not remain here long, and uncertain if we shall remain here one hour. This last assumption is our condition."

The Wager is a choice to live differently in the world - not with the goal of reaching a specific tier of the afterlife - and more importantly, “You must wager. It is not optional.” Think about that for a second. When faced with boredom and death, you can choose to believe in God - or some divine order - you can choose to live your life as though there is something else you are supposed to do besides distract yourself. Or you can choose to think that none of that matters, and live your life knowing that nothing matters and that we’re all in a howling void of boredom and death. But what you absolutely cannot do is steer clear of that choice; we have to live our lives having actively chosen one of those. We are not gambling that God exists in case we get to go to Heaven someday; we are gambling that God exists so that there can be something, anything more to our lives than boredom, distraction, and death. We have to know that we are faced with boredom, distraction, and death, and then choose whether we want to act like there’s something more that we just don’t know about yet. We have to decide whether to gamble on an option that allows us to live without driving ourselves into cruelty or insanity.

Now, I didn't write this essay to diagnose Joseph Strickland or the other bishops from afar. I didn't write this to say "ah yes, they have clearly chosen the wrong way and I chose the right one," even though Pascal may have nailed these particular bishops when he wrote:

“…this same man who spends so many days and nights in rage and despair for the loss of office, or for some imaginary insult to his honour, is the very one who knows without anxiety and without emotion that he will lose all by death. It is a monstrous thing to see in the same heart and at the same time this sensibility to trifles and this strange insensibility to the greatest objects."

I really wrote this essay because a few centuries ago, this particular Catholic theologian - one who was famously critical of his church and wrote a lot of essays making fun of clergy he didn’t like - thought that we were all plagued by boredom and distraction, and that to get out of cycle of misery, we were going to have to make an active choice, we were going to have to gamble on there being something more to this, and a lot of people were making the wrong choice.

And a few decades ago, Renata Adler wrote Speedboat to show us, among other things, what happens when too many people make the wrong choice, in a world where "boredom and cruelty are great preoccupations in our time. They flourish in a single region of the mind."

You see, Speedboat isn’t just about everyone being bored and aimless. It’s about how that boredom and aimlessness reduces modern life to an endless cycle of acts of aggression. “All acts are acts of aggression,” Adler’s characters say, and Jen herself says that "When I wonder what it is that we are doing— in this brownstone, on this block, with this paper— the truth is probably that we are fighting for our lives."

Speedboat isn’t just that one story about riding along in the boat until somebody breaks her back. It’s stories about the glares people give each other on the subway, the meaningless betrayals of confidence that shatter relationships, the insufferable noise we all drum into each other’s lives, and how “Every love story, every commercial trade, every secret, every matter in which trust is involved, is a gentle transaction of hostages." Eventually, fed up with the constant constricting unconnected stresses in her life, Jen says something that I say to myself every time anyone posts about Catholicism on the internet:

"Suppose we blow up the whole thing. Everything. Everybody. Me. Buildings. No room. Blast. All dead. No survivors. And then I would say, and then I would say, Let’s just have it a little quiet around here."

Jen is fed up with her screaming migraine of a world, and frightened of something else that she's starting to notice: all of those acts of aggression around her acting as accelerants for each other, taking shape, gaining lives of their own. Stop me if this sounds familiar:

"I said I thought there was such a thing as an Angry Bravo— that those audiences who stand, and cheer, and roar, and seem altogether beside themselves at what they would instantly agree is at best an unimportant thing, are not really cheering No, No, Nanette. They are booing Hair. Or whatever else it is on stage that they hate and that seems to triumph. So they stand and roar. Every bravo is not so much a Yes to the frail occasion they have come to make a stand at, as a No, goddam it to everything else, a bravo of rage. And with that, they become, for what it’s worth, a constituency that is political. When they find each other, and stand and roar like that, they want, they want to be reckoned with."

Again, feeling that your life is not attached to a recognizable narrative structure, that you are not a saint or a historical figure or a main character, can be unpleasant. It can be downright scary. It can be something that would leave you paralyzed, unsure what the hell you were supposed to do with your life, unsure if you were just one messy accident. And maybe everyone else felt like that too, and they all got together and decided to ruin everything for everyone. Maybe that was how they decided to distract themselves, through aggression, through pure tooth and claw. Maybe they want to be in a war and they don’t really care who wins, just as long as there’s some sort of war to provide a scaffold for the gelatin of our lives. It's distraction, and they're not willing to gamble that there's more to life than that.

Maybe that gets us a little closer to understanding why the bishops think their job is to be part of the Angry Bravo.

The first thing I ever wrote for G.O.T.H.S., the first weird Catholic thing I ever saw that made me say "huh that's pretty weird, maybe people should know about this" was the "Combat Rosary". Far-right internet-poisoned Wisconsin priest Rick Heilman was selling them as part of his broader "Roman Catholic Man" online project. When I've prayed the rosary in the past, I've found it a source of comfort in scary times, especially given the contemplative and repetitive nature of the prayer. It was very difficult for me to identify with someone praying the rosary and seeing it as "combat" or "warfare". Heilman is still selling these rosaries; here's the copy on his site for the new "Combat Rosary - Patriotic":

"This is the “authentic” Combat Rosary originally designed by Father Richard Heilman, who was inspired to design this Combat Rosary based on the 1916 WWI US Government military issue pull chain service rosary. The Pontifical Swiss Guard (who guard the Pope) now, daily, carries Father Heilman’s authentic Gun Metal Combat Rosary, as their official rosary. Father Heilman designed this Combat Rosary to use the most powerful of sacramentals by adding the Benedict Medal and Pardon Crucifix, which makes it a powerful spiritual assault weapon against evil forces. The Patriot Combat Rosary is unique in that the centerpiece is designed in the shape of the United States of America, as we are called to pray for our country and ask God to Make America Holy Again! The images and inscriptions match those found on the Peace Through Strength Challenge Coin."

One of the last things I ever wrote for G.O.T.H.S. included a look at Rugged Rosaries, a small Catholic business that, wouldn't you know it, also sells combat rosaries. Here's the copy from their website:

"This compact all-metal Chaplet is rugged, functional, and portable. It has a meaningful history, as it is reproduced in the same style of the service combat rosaries issued by the government to soldiers, sailors, and flying aces during WWI, hence the name. This version is in the configuration of the St. Michael Chaplet. We have faithfully duplicated the historic rosaries with the same type of pull chain used in military dog tags, so you know it's strong…St. Michael is the patron saint to lead you in the Catholic army. He is the patron saint for Soldiers and all Law Enforcement and is the most popular Saint requested by our customers."

And then, for good measure, here's the copy from a different website called leafletonline.com, which sells a USA Rosary and a Patriotic Rosary and a Crusader Rosary and a Battle Rosary and, you guessed it, a Combat Rosary (that is somehow distinct from the Battle Rosary):

"The Church Militant Combat Rosary, also known as a Service Rosary, is based upon the original pull chain rosary that was commissioned and procured by, believe it or not, the U.S. government and issued by the military, upon request, to soldiers serving in World War I. Some of these rosaries were also seen in WII. Veterans recognize them as "Service Rosaries." Made of strong metal pull chain, this rosary is meant to endure. Special locking jump rings add to this rosary's toughness. This rosary's endurance is meant to highlight the hopeful words of Psalm 136: "His love endures forever." This Combat Rosary's use of the Pardon Crucifix, Miraculous Medal and St. Benedict Medal makes it a powerful spiritual assault weapon against evil forces attempting to separate us from the love of God and His will for our lives. Also, be sure to check out the Church Militant Books and Manuals for invaluable information and training in the fight against evil. What is included with your rosary?: Small spiritual ammo tin with carry handle (looks like a military ammunition box)."

It is very difficult for me to articulate (or even really understand) why I still care about being Catholic, even when the men who run my church keep doing stupid shit. But the men who ran Pascal's church did a lot of stupid shit, too, so I can at least start where he did: I am actively making the decision to gamble that life is more than boredom and cruelty. If I didn't do that, I'd have to gamble the other way, joining a bravo of rage, a bravo that wants to be reckoned with, a bravo where my Catholicism and my prayer life is now about dominance and warfare, to the point where I'm buying rosaries marketed as assault weapons that come in ammo cans. That would be one possible response to boredom, I guess, but it seems like one that would rot me from the inside. And it seems like a lot of people, including people who run the church, are choosing that response.

Again, if there is more to this, more to just throwing myself into a destructive endless personal war against humanity for no reason other than passing the time, then believing in that "more" is, at best, a gamble. But I have to gamble one way or the other, it is not optional. And I'm scared of the person I would be if I gambled the other way. As Pascal wrote, “How can people hold these opinions? What joy can we find in the expectation of nothing but hopeless misery? What reason for boasting that we are in impenetrable darkness?" And as Alder wrote, "I think sanity, however, is the most profound moral option of our time." Without giving too much away about the ending of Speedboat - it’s a good book and it’s worth reading - by the end of the novel, Jen has made the choice, however reluctantly, to treat her life as though it means something. Not because she’s a hero, not because she’s a warrior, not because she's a saint or historic figure, but because she’s scared of what kind of person she would be if she didn’t make that choice. She needs that moral option of sanity.

I don't know what that "sanity" in the face of boredom actually looks like. But I suspect that, for a Christian, it would require re-orienting our lives from a response to boredom into a response to material suffering, and, given our limited ability as individuals, beginning to act collectively to address the causes of that suffering.

Speedboat clearly influenced Wallace’s approach to “tornadic” story structure and discussion of “anti-confluential” narrative art in Infinite Jest. Speedboat also pretty obviously influenced Wallace’s unfinished novel, posthumously published as The Pale King, which is similarly structured and very explicitly a novel about boredom and how a group of people (in this case, IRS agents in downstate Illinois) choose to react to it. I am putting this information in a footnote because I wrote an essay about Wallace before and had multiple people reach out to me to say “please stop writing about David Foster Wallace”.