The Catholic Media Flowchart

It just feels like not enough people have been asking these questions lately.

“Still and all, why bother? Here’s my answer: many people need desperately to receive this message: ‘I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people don’t care about them. You are not alone’.”

-Kurt Vonnegut in Timequake

“Over the past few months, the internet has been teeming with memes riffing on singer Charli XCX's latest album, "BRAT." Though the internet has yet to settle on one single definition, being "brat" is decidedly a good thing. (In what could be taken as an endorsement, Charlie XCX herself once tweeted that "Kamala IS brat.") As her feast day is Oct. 1, I think it's only fitting to add St. Thérèse of Lisieux to the list of all things brat. Allow me to explain.”

-Stephen G. Adubato, writing for National Catholic Reporter in September 2024

My original title for this piece was “Should I Really Publish This or Just Kill Myself: The Complete Guide to Writing for Catholic Media”, but I backed off of that because it was too wordy and too edgelord-y. I don't think you should actually kill yourself. Being alive is good (I think?). But recently, I’ve been coming around to the thinking that more folks in Catholic media should at least be asking the “should I really publish this” half of the question. My Substack Pal and Lutheran pastor Benjamin Dueholm wrote a very good and introspective piece last November after we all learned which version of the future we were getting, and he wrote this towards the end of it, and it got me thinking about why people - including me - write anything about the world at all:

“We can write and read about the ironies of 2024 or last summer’s fad for polyamory or dissect the psychology of tradwife content, but all of it is vamping until someone figures out how to communicate hope in a larger sphere than our therapy sessions or our sex lives. We can’t gain what we don’t want, and we can’t want what we don’t imagine.”

My main take on polyamory is that it seems like it would be very stressful. My point (and to some extent Ben's point) is, in an era where it feels like everything is getting worse all of the time and we need to start thinking about our lives and our communities in radically different ways, so much of what we read online is just this bullshit vamping that doesn't provide any new information or any useful reflection, nothing that provides the reader with any hope or comfort or even entertainment, nothing that says anything besides “I hit a word count so I can cash a check for $27.” You can see this all of the time in every kind of media outlet, including Catholic media.

Now, I’m not referring to Catholic journalism; my main complaint about Catholic journalism is that there isn’t nearly enough of it. The reporters who do the work of calling dioceses and digging through old parish bulletins and tax filings and generally getting information that powerful people in the church would rather keep quiet? Those folks are all great, and good Catholic journalism can be found in all sorts of places like National Catholic Reporter and FemCatholic and Where Peter Is and believe it or not even America and Crux. But, of course, those pieces require research and legal reviews, and all of that usually costs a bunch of money, and “look Nikki Glaser made a joke about Conclave! That probably says something about Society!” doesn’t cost a bunch of money, so we get a lot more of the latter than the former.

I’m also not talking about right-wing outrage bait; I’m really over saying “look at this terrible piece at Crisis or LifeSite” because we all know they are terrible. The type of work I’m talking about today is everything else: personal reflections, book reviews, political musings, discussions on a moral question. Persuasive writing, even if the only thing you're trying to persuade the reader of is “reading this is worth your time”. Freelance theology. Almost all of the writing that you can find in major Catholic media in this broad genre is, bluntly, unbearable, and I hate that, because it's the majority of the writing that makes up major Catholic media's output.

Now, do I do this kind of writing all of the time? Yes. Am I better at it than every single person I’m about to criticize in this piece even though I’m just out here doing it for love of the game, and can I show you the reasons why I’m better at it in a handy visual aid? Also yes. But let’s start somewhere else first.

There was a piece in mid-December at Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal which I found truly remarkable and innovative in terms of how worthless it was. The piece, titled “Can a Catholic Attend an Invalid Marriage?” is by Gregory Caridi, a canon lawyer who works for the diocese of Dallas1 and presumably meant to use the word “wedding” instead of “marriage” since that’s the thing you actually attend. And though this essay comes across as very technical and analytical, it is, ultimately, intended to be a persuasive piece. Caridi is trying to persuade his reader that his answer to the question posed in the headline is the right one, for the right reasons, and, like any writer who publishes something online, he is trying to persuade his reader - presumably one who is at least somewhat knowledgeable when it comes to Catholic moral teachings - that reading this piece will not be a complete waste of time. So let’s see how he does it.

I certainly don’t want to keep you in suspense: the answer to the question that Caridi poses in his headline is “no”. When, in the second paragraph of his piece, Caridi notes that “The fundamental moral issues underlying this question relate to cooperation and scandal. That is, if one attends a wedding which celebrates an invalid union, is the person in attendance cooperating in the sins related to the invalid union? More directly, does attendance encourage and celebrate another’s sin? And further, would this attendance engender scandal, in that others may feel there is no issue with the wedding and intended union in light of the open encouragement?”, he is going to answer with “yes”, “yes”, and “yes”, respectively. His reasoning is not surprising: if the parties getting married are committing a grave sin according to Catholic doctrine and canon law, a faithful Catholic cannot attend the wedding without giving tacit approval to the grave sin and thus getting the stinky gravy of sin upon themselves.

“It is always wrong to attempt to marry with improper matter (a man with a man or a woman with a woman), and it is always wrong to marry someone when one of the individuals already has a spouse, as this amounts to adultery. Similarly, it is wrong to encourage or support someone else in doing these things. It is wrong because the object to which you are encouraging the person (an attempted union contrary to divine and natural law) is by its very nature wrong. For this reason, if attending a wedding celebrates an action which is contrary to the divine or natural law (two people of the same sex attempting marriage, a polygamous union, a marriage where one party is already married, etc.), the Catholic should abstain.”

You may be wondering “Tony, is this just a really long and dry essay explaining that Catholics shouldn’t go to gay weddings?” and the answer is “it sure feels like it”. But where Caridi goes above and beyond, where he makes a decision that ultimately made me want to show this piece to all of you, is that he concludes with the tool used throughout time immemorial to deliver devastating rhetorical and moral blows: a flowchart.

You’ll notice that there’s only one green bubble on the flowchart at all, only one very specific set of circumstances in which a Catholic can attend a wedding of which the church does not approve; the fact that all but one path of the flowchart ends in the exact same place calls into question the purpose of, you know, using a flowchart at all. But: if you want to go to an evil invalid wedding, the marriage has to still conform to divine law (not be gay), you need a pressing reason to attend, the couple getting married has to be unaware that their marriage is invalid, you have to make sure you're not encouraging the couple to reject church authority (LAME), and you have to be certain that you won’t cause scandal to others, and even then you can’t have an active role in the wedding so God help you if you give a toast at the reception.

Caridi provides information to support his conclusion, but none of it is new. He cites the Code of Canon Law multiple times, and that hasn't been updated since 1983. He points out that the church does not approve of marriages that do not conform to their understanding of divine law, which you've known for at least twenty years. “The church says it's bad, so you shouldn't be there” is a point of view that you're allowed to have (I think?), but it's not one that you're allowed to present as novel or worth anyone's time in late 2024 in a journal of ecclesiology run by a major Catholic university that just won 75% of its postseason football games. Also, you may have noticed that Caridi refers to human beings as “proper” or “improper” “matter”, in case you were worried that he wasn't doing enough to literally dehumanize people.

If you’ve read basically anything I’ve ever written before, you’ve already anticipated my next critique: moral decisions do not easily reduce to a flowchart, especially a decision with deeply personal ramifications like “should I attend my friend or family member’s wedding, or instead tell them that I do not acknowledge their marriage as valid?” Caridi has omitted any real consideration of existing relationships between the moral agent and the people getting married, between the people getting married and the institution of the church, between the moral agent and the other attendees at the wedding. Caridi does not consider that existing relationships could potentially impact your decision to even be adjacent to a relationship or an act deemed “invalid as a result of natural or divine law”, suggesting that it cannot impact that decision at all, which is clearly untrue to anyone who has ever interacted with another person before. As we’ve talked about before, being “pastoral” or considering moral decisions in their fuller relational context is not a separate type of Catholicism that is somehow watered-down compared to a canon law flowchart. A canon lawyer explaining moral decision-making using a flowchart makes a mockery of the entire 2,000-year field of Christian theology; the only comfort I can take in Caridi’s piece is that it’s published online and not in print, so at least nobody wasted any paper. These are words, divorced from any action, divorced from any reality, free of any new information or perspective. I am staring into the void, which is not how I should feel when I am reading a persuasive essay about Catholicism.

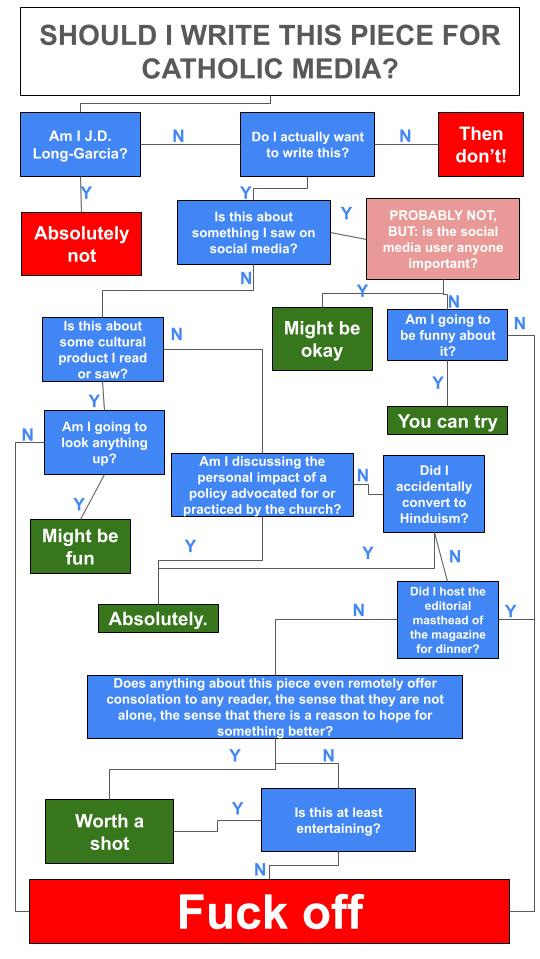

There are a million and one ways to waste time on the internet: games about candy, guitar tabs of popular show tunes, countless amateur short films of people making love. If a person writes an essay about Catholicism, they do need to persuade the reader that the essay is more worth their time than all of that other stuff, and they need to persuade the reader that their writing of the essay in the first place was a better use of time than all of that other stuff. It is thus in the spirit of fraternal correction towards all Catholic magazines, journals, and blogs that I have made my own flowchart addressing whether a moral agent should really attempt to write and publish a piece in Catholic media or just kill himself. Again, don't actually kill yourself. But also, don't actually write that piece.

We will look at each branch in detail, but to begin, here is the entire flow:

You can see that this is messy. This is a complicated process, and the flowchart won’t be perfect. “Might be fun” and “worth a shot” are recommendations from the chart that could, if you’re not careful, result in some real dogshit essays. But I think that if we step through this branch by branch, with real examples taken from multiple mainstream Catholic outlets, we’ll be able to put together a set of useful principles for deciding whether to write a piece, and whether that piece will be worth a reader’s time. So let’s start at the top:

The first and most important question that anyone hoping to write for Catholic media should ask themselves is “am I J.D. Long-Garcia, current senior editor for America media?” And if the answer is yes, then he shouldn’t write that piece, or any piece. I’ve used Long-Garcia as a punching bag several times before, and I don’t want to belabor my point here or make absurd over-the-top ad hominem attacks, so all I’ll say before moving on to our examples is that J.D. Long-Garcia has done for the craft of essay writing what Mohamed Atta did for New Formalist architecture.

Example (bad): “The Repeal of Arizona’s Abortion Ban is More Than a Political Loss”, by J.D. Long-Garcia in America, a piece so ignorant and incurious that I was surprised its author was at all familiar with the written word. This would be an example of a “bad” piece, going off of the standards of the flowchart, as it is by J.D. Long-Garcia.

Example (good): “The Tortured Prophets Department”, by Tony Ginocchio in Grift of the Holy Spirit. This piece passes the first test in the flowchart, as it is not by J.D. Long-Garcia, and is in fact a piece making fun of the above piece by J.D. Long-Garcia. “It appears that his job…is to wait for the bulb that says “abortion” to light up, and then push the button in front of him that shits out an essay. Intellectually and morally, he is on par with a lab rat in a maze. J.D. Long-Garcia is not a serious person and his ideas are not worthy of serious consideration.” is not a set of sentences that J.D. Long-Garcia would ever write.

Following the first break in the flow, we get to a very underrated question in Catholic media, “Do I actually want to write this?” Specifically, if you write something, it should actually make sense to you, and it should be something that you care about, and we should know, from your writing, that you care about it, because that care is what makes good writing compelling to read, is what connects you with a person who cares deeply about the same thing. Sometimes, Catholic outlets have a tendency to take whatever current event is relevant at the current moment and try to make hay with it, with disappointing results.

Example (bad): “Praying for the president” by Thomas Reese at Religion News Service. I used to have a joke about Reese, that he was a guy who had been writing about American Catholicism for almost fifty years and he writes every essay like it’s his first day learning about Catholicism or America (or both). But this guy actually used to be editor-in-chief at America magazine back in the early 2000s while America was getting yelled at by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, leading to Reese’s eventual resignation in 2005. So I think Reese just keeps turning in these naive bland pieces every day because he’s too gun-shy now to express any sort of strong opinion; barring that, it’s possible that some old school America superfan is holding him captive in a James-Caan-in-Misery-type situation and forcing him to type out terrible essays for RNS. Anyways, in this piece, he explains that we should all pray for Donald Trump during his second presidential term, and towards the end, you get the sense that he’s really stretching to hit the end of his word count and/or find anything pleasant to say at all about the incoming administration. “We also need to remember that presidents can always surprise us by being unpredictable. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the war hero, ended the fighting in Korea and warned of the military industrial complex. Johnson and Carter, both Southerners, embraced civil rights for Black citizens. Richard Nixon started the Environmental Protection Agency, ended the Vietnam War and established relations with China. Ronald Reagan signed nuclear weapons agreements with the Soviet Union.” Again, I think all of these are great things to say if it’s your first day learning anything about America, or if you had never noticed that Donald Trump was already president for four years so we maybe have a good idea of his governing style and priorities already. Then Reese, who realizes that he still hasn’t made it to 1,000 words, just starts listing a bunch of problems for multiple paragraphs, as reasons to pray for governments. Even some of the problems feel half-assed: “The last time the federal budget was not in deficit was during the presidency of Bill Clinton. Too many people continue to die from guns and addictions. Health care and higher education costs are out of control. In too many parts of the country, there is a housing shortage, causing high prices and high rents. Government paperwork stifles innovation. The rollout of new websites for Obamacare and student aid were disastrous.” The final lines, “We need to pray for one another. We all need conversion so we can respect each other and work together for the common good,” may as well have read “look what do you want me to say”. But I do sincerely think there is value in prayer, and I do say five decades of the rosary every night so that government paperwork may no longer stifle innovation.

Example (good): “how to build a library” by Renée Darline Roden on her Substack. Renée’s writing is wonderful, and this is one of several instances in the past year (this is the other one) where Renée took a topic that literally every Catholic writer had already attempted to tackle - Harrison Butker’s commencement speech at Benedictine College - and did a better job than everyone who rushed in with a hot take. Renée actually observed the commencement firsthand and had a specific, personal point of view about it that wasn’t just getting in a “gee disrespecting women doesn’t seem very Catholic” piece to mark time like everyone else, but rather something she felt deeply and believed was key to understanding how we make the world better, something she believed we should all spend time thinking about, because it had real stakes. This particular piece is a great example of Renée’s righteous epistemological fury: “We all have ideas, insights, and the valuable wisdom of our own lived experience, which we turn into wisdom through reading and thinking. That’s called formation and we call that formation an education. Rather than contextualizing any of his lived experience in the wisdom of literature, the tradition of thought our ancestors have taken the trouble to pass down to us through 5,000 years of oral history and the written word, this speaker simply reached for the dog whistles of those who are distressed with change, don’t know why, and so want to resurrect the past for reasons they do not fully understand.” Unlike Reese, who has only been writing about Catholicism since 1978, Renée gets that you’re allowed to be mad about how stupid everything is, and that articulating that anger might be valuable in helping other people process these stupid events and find a way out. This piece is also a great example of her sense of humor: “If Benedictine College was looking for an agitator, they should have selected Peter Maurin. (The fact that Maurin died in 1949 would seem to pose an immediate problem, but what with AI holograms or Google Gemini or some such, I feel confident even a freshman in their dorm room could cobble something together.)”

Moving on, to probably the most dangerous territory on the flowchart:

If you are about to pitch to a Catholic outlet with “here’s an essay about some posts I saw and What It All Means About Faith And Society”, my immediate response to you is “I already said at the top of the piece that you shouldn’t kill yourself so I’m not going to say that now, however I’m really not happy that you’re doing this.” In the history of posting going back to Michel de Montaigne, there have been maybe three important posts, so nobody should write about posts, ever. There are a few ways around this rule: you can write about posts if the person posting it has some level of cultural relevance, and you can write about posts if you’re funny (I’m funny).

Example (bad): “Social media in flames: Pope targeted for not preaching fire and brimstone,” by Cindy Wooden in Catholic News Service (this one purports to be a news piece moreso than an opinion essay, but you’ll see how the rules apply here pretty quickly). After Pope Francis made a statement in early 2024 that “I hope hell is empty”, Wooden detailed some of the back-and-forth posts on Facebook and Twitter/X in response to the Pope’s interview, people quoting contradicting Bible verses to each other and arguing over whether God was all-forgiving, or whether Hitler was definitely in Hell. It's hard to understate the importance of CNS’ ostensible news story: this is neither important, nor a news story. The who/what/where/when that we normally look for in news stories is this: an unspecified number of unidentified posters made an unspecified number of unspecified posts at each other, concerning a person who was not responding to any of those comments and likely never saw them at all, over a certain unspecified length of time following an offhand comment by the Pope that was explicitly preceded with “eh this isn't me teaching anything I'm just thinkin'”. This was not a “firestorm”, to use a term that Wooden picked and put in the body of her piece. Wooden did not identify a single commenter who was in the church hierarchy, in Catholic media, or any other position of importance of any kind besides “person who uses Facebook”, presumably because she didn't see any. There is only one named social media account in the entire piece, and when Wooden’s piece ran, it had 384 followers. Wooden could have found a bigger story by interviewing the guy yelling at people outside of my very busy Jewel-Osco.

Example (bad): “Don’t Celebrate Murder,” by Fr. James Martin, SJ in America. While I agree with Martin’s headline, he spends the first half of his piece lamenting the collective celebration over the assassination of UHC CEO Brian Thompson, without actually establishing that what he’s looking at is any sort of widespread trend; the evidence he offers is a piece in Axios (which is just a rollup of a bunch of anonymous social media accounts), an anecdote in the New York Times about a spike in hooded sweatshirt sales, and “A quick glance at Instagram and TikTok reveals posts—I’m sure you’ve seen them”. I actually hadn’t seen widespread celebrations of Thompson’s murder in my social media feeds, not nearly as much as I had seen anger and frustration over how much our country and our healthcare industry had failed us so badly that things had led to this, or frustration over our criminal justice system’s desperation to call this guy a murderer but not the oligarchs who work to keep us from receiving healthcare. Maybe Martin saw more spiteful glee in his feed than I did in mine, maybe he saw something and I saw something else and we both saw real things, but then that just leads me to the question: why the fuck do I have to read a piece about strangers in his social media feed? He certainly didn’t establish that anyone important was engaging in this behavior. Also, why are the Jesuits preemptively scolding Instagram accounts? There are orders of sisters actually trying to squeeze UHC into explaining their appallingly high rates of claim denial. Does that seem like a more productive reaction to this tragedy? Martin spends the second half of his piece roundabout-comparing those not mourning Thompson to the January 6th Capitol rioters, the Nazi regime in Germany, the Tutsi regime in Rwanda, Cain murdering Abel, David killing Uriah, Saul trying to kill David, and oh yes, Judas Iscariot betraying Christ. It’s the kind of ridiculous rhetoric I would expect from LifeSite when they write their monthly “How Gay Is James Martin?” pieces. I honestly expected better from Fr. James Martin, SJ.

Example (good): “You Really Don’t ‘Gotta Hand It To’ Archbishop Weakland,” by Tony Ginocchio in Grift of the Holy Spirit. This is a good piece because, while it’s about posts, it’s about a bad post by someone relatively well-known in Catholic media: Fr. James Martin, SJ. Also, it’s funny, as it’s parodying a time Martin put his foot in his mouth pretty hard after the death of retired Milwaukee Archbishop Rembert Weakland. Martin poured one out for his friend on Twitter, and then a bunch of people jumped in to note that Weakland was an especially egregious participant in the coverup of widespread sexual abuse in his archdiocese, and actually had to resign in disgrace, and never really appeared to even feel all that sorry for what he did, and actually all of his awful actions to cover for sexually abusive priests are things he admitted under oath. Martin explained that Weakland was his friend and friends forgive each other, which he thought sounded like the high road, and then he had to walk that all back because “everyday sinfulness” and “the crimes of sex abuse” were, in fact, two different degrees of evil that require two different degrees of the Power of Friendship to excuse. Weakland also once used $450,000 of archdiocesan funds to settle a lawsuit with a man who had accused him of date rape, and I’m glad Martin was also brave enough to forgive him that. Still, I never wrote an op-ed titled “Jesuits, don’t celebrate rapists” becaue I didn’t have enough to establish that Martin’s post reflected a widespread trend.

Moving to our next branch:

Here, we’re in the realm of reviews and analysis of culture, usually pop culture. What can the Catholic church learn from Taylor Swift, or some shit like that. These can be fun, and every outlet needs to run them to keep the lights on, but the key to success here is you have to look stuff up. You can’t just be like “I read/saw this thing and I like it”, because then your reader should just read/watch that thing instead of spending time with your bullshit. You have to look stuff up to bring in new information and perspective that makes the essay worth a reader’s time, and perhaps most importantly, you have to look stuff up to make sure you don’t come across as a huge fucking idiot.

Example (bad): “Links 6/24/21,” by Michael Sean Winters in National Catholic Reporter. Sometimes Michael Sean Winters doesn’t have an idea for a column and he’s got a deadline to hit, so he just lists the tabs he has open and sends that to his editor. In this installment, Winters observed the fifteenth anniversary of his favorite movie The Devil Wears Prada, critiquing a thinkpiece in Salon with “the subhead of the piece, "The real villain was exploitative work environments all along," may be accurate at one level, but can we just let a movie be a movie? Not everything has to be reduced to its sociological or political consequences, does it? Why so super-serious?” While “Michael Sean Winters Joker” is a character I am interested in exploring for a future piece2, I even pointed out at the time that this is not only a fundamental misreading of a fundamentally easy-to-understand film on a par with Roger Ebert saying that Look Who's Talking would have been better without that talking baby3, but that this message and Meryl Streep’s caricature of Anna Wintour had actually become more relevant as time has gone on: two weeks before Winters turned this piece in, workers at Conde Nast had marched on Wintour’s house because she was being a shitty and exploitative boss. The movie is based on a novel, and the novel is famously a roman a clef by an author who was literally Anna Wintour’s personal assistant. It's about how working for Anna Wintour is miserable, which it apparently still is right now. None of this is difficult.

Example (bad): “Blessed are the brats: Thérèse of Lisieux flips entitlement on its head,” by Stephen G. Adubato in National Catholic Reporter, the essay I quoted at the top of this piece. One of the things you have to look up in a review of a cultural object is the object itself, and I sincerely do not believe, from the information he gives me in his essay, that Adubato has ever listened to brat, the 2024 Charli xcx album about “doing cocaine” and “feeling kind of bad about how much cocaine you’re doing”4. I think Adubato really just wanted to write about Thérèse of Lisieux, and that would have been a perfectly reasonable essay to run in a Catholic outlet the same week as her feast day. Unfortunately, it feels like the editors forced in a shitty opening graf about how the Little Flower of God is kind of like brat, an album about which Adubato mentions zero things for the rest of the essay, and gives no indication that he’s listened to any part of it, he just talks about Lisieux’s autobiography and our calling to detach ourselves from the desire for worldly gains. A perfectly inoffensive piece made to feel forced and inauthentic, and it’s not even the only brat shoehorn I’ve made fun of in the past six months.

Example (bad): “All Young Men Should Watch the Movie Gladiator,” by Fr. Mike Johns in Word on Fire. This one fits nicely into Word On Fire’s favorite genre: bitching about how people aren’t masculine enough, and the way to fix that is to watch movies Jesus Christ how did this site ever become popular. “We live in a society devoid of heroes. Or, perhaps stated more accurately, we live in a society that is afraid of and dislikes heroes—those who call us to be better and who remind us that we could be more than we otherwise are. So, the many so-called heroes in modern society turn out to be empty shells—empty because they have no real sacrifice to make, such as the heroes of the Marvel universe, or because their moral characters are hopelessly compromised, as in a George R.R. Martin story.” Sure, fine, Deadpool has been sissified, whatever, if Fr. Johns likes movies about gladiators5, that’s his right. Johns even includes a few films that did a good job depicting masculinity: “There are a few films made prior to our culture’s complete rejection of ethical heroism in which the link between sacrifice and love is still preserved. Such films include The Lord of the Rings (2001–2003) trilogy and Braveheart (1995), and serve as a check on modern apathy. It is doubtful that such films could be made today”. While I agree with Johns that studios wouldn’t make Braveheart today - likely for a different reason than he thinks - I think that if you make a statement like “it’s doubtful that anyone would make a Lord of the Rings film today”, you should have to look up things like “are there three Lord of the Rings films slated for release in the next two years?” Less than a month after Johns’ piece, War of the Rohirrim hit theaters, which, while an animated film, was still produced by Peter Jackson, still made by Warner Studios, and had a high-profile voice cast including Brian Cox in the lead role. The two-part live-action film The Hunt for Gollum, which is also produced by Peter Jackson and will return actors from the original franchise including Ian McKellen as Gandalf and Andy Serkis as Gollum, is scheduled for a 2026 release. This glaring error in Johns’ essay is unsurprising given that it ran at Word On Fire, and every writer at Word On Fire takes his cues from Bishop Robert Barron, a man whose primary engagement with books is evidently less “reading them” and more “getting bludgeoned in the head with them”.

Example (good): “Ramona the Real,” by Mollie Wilson O’Reilly for Commonweal. Commonweal is generally the best at publishing essays about art and culture that are actually good and well-researched and in-depth, but even this short and sweet piece by one of my favorite Catholic writers gets it done. The thesis of the piece is “it’s Beverly Cleary’s one hundredth birthday and we should take a minute to appreciate how great she is at capturing what childhood feels like”, which is correct, and O’Reilly also brings in contemporaneous reviews of the Ramona novels and a comparison to George Eliot’s work. She read more than one thing! She looked stuff up! She has an original perspective! It’s sweet because it’s about books she reads to her kids! Why is it so hard for everyone else to do this!

Once we’re out of the realm of “social media bitching”, and out of the realm of “culture reviews”, we get into some more dangerous territory: “personal essays”.

Here, the main subject is you, or something that happened to you. It’s tough to get these right; everyone tries, few pull it off. Remember, when you write about yourself, you are still competing for eyeballs with countless amateur short films of people making love, and you have to prove that you’re worth the time. Now, there are a few avenues within this realm that have a much higher-than-average success rate. The first is that you are always allowed to discuss the real, material impact of a policy advocated for or practiced by the church, upon you, a human being. You are also allowed to write and publish the essay if you accidentally convert to Hinduism partway through writing it.

Example (good): “Catholic school employees have a choice to make, now that their protection is in peril,” by Matt Tedeschi in National Catholic Reporter. In contrast to the “the church says it’s bad so we should just listen to them” flowchart that Caridi gave us at the beginning of this piece, Tedeschi shows us just how personal policy can get. He was a respected and Yale-educated6 high school religious studies teacher who got shitcanned and ostracized by his employer after a student outed him as gay, and he had no recourse as his employer claimed that he fell under a “ministerial exception” for labor protection and non-discrimination laws. Thanks to recent case law, “Practically all Catholic elementary school teachers and likely most high school teachers will now be seen as "ministers." It is also likely that coaches, deans, guidance counselors, admissions counselors, student activities directors and many other positions will be considered "ministerial…Now that [these cases have] hollowed out employment rights for Catholic teachers, it is up to them to decide their fate. Perhaps the last remaining means of preserving both the civil rights of teachers and the religious values they hold dear is to organize for truly fair contracts. Otherwise, they will remain vulnerable to discrimination, harassment, and retaliation — and there will be no way out.” The church actively practices policies like these and spends resources to defend them in court, and Tedeschi provides us with a powerful reminder of what the church is actually fighting to do, and who they’re fighting to hurt, and what people are going to need to do to oppose it.

Example (good): “A postmodern Catholic divinity student lets go for a moment of grace,” by Art Blumberg in National Catholic Reporter. I love this piece. This is so great. A grad student has to observe a Hindu puja for class and accidentally converts to Hinduism midway through the assignment as he observes the statue of Ganesha. “As I take notes, I think that there is something inspiring and satisfying about seeing a religious observance done well. The pujari waves a short-handled stick with flowing tassels. I watch this intricate ritual, wondering what it all means. It’s then I realize I am doing this all wrong. I am observing, taking notes like a field anthropologist. I am drawing parallels to Christian and Jewish practices.” That’s because you are a field anthropologist! People are worshipping a god and it’s not your god! You’re allowed to observe! But Blumberg attempts to let go of his preconceived framework while observing the ceremony and, as becomes obvious the further you get into the piece, straight up starts worshipping Ganesha, I love it so much. “Just breathing. Just being. Silence. I am startled. The two voices begin a new and joyous chant. Is that a bell tinkling? The statue of Ganesha. The chanting. The distant dance of bells. Ganesha. For a moment, the eyes of Ganesha are all that exists, all that is there in my world. As the puja ends, I am still staring into Ganesha's eyes…A great feeling of peace comes over me as I surrender to the puja. For the moment, the story becomes a little more my own. The pandemic has upended the way we live. Yet even a pandemic cannot stop our seeking, our questing for signs of the Divine.” Now, some of you might say that Blumberg did not actually convert to Hinduism, but rather came to a realization that the world's major religions are fundamentally unified in their purpose, albeit divergent in their social practices and interpretations. Which is a fair assessment, and also known as “converting to Bahá’i”. No judgment here, I’m always five minutes away from converting to Bahá’i myself.

While these were good examples, there is still an inherent risk with publishing these more personal essays: the author could just be straight-up lying about what they believe and how they practice their faith, in ways that are extremely easy to discover. So if you’re a well-resourced Catholic magazine run by a famously educated order of priests, it would be incumbent upon you to make sure that the guy who just sent you a piece isn’t completely full of shit, even if he just invited you over for a very nice dinner.

Example (bad): “Lowering the temperature in Catholic culture wars—over a meal,” by Tim Busch in America. Busch is tired of all of these culture wars, and it’s time to finally break bread with those who may disagree with us. Busch has been inviting big names in Catholic thought to dinner over the past year, explaining that “We then retire to the table, where we discuss our personal stories—how we came to the faith, how it has changed our lives, our favorite Bible verses and so on. The guests have movingly described their walk with Christ; many have been overcome by emotion. When we have broached the tough topics, we have maintained a spirit of mutual respect, not rancor. The focus is not on the issues themselves but on the relationships among those present. At the end of the meal, we take a group photo and share personal contact information, encouraging everyone to stay in touch.” Apart from some ominous asides like “To be clear, on many such issues there cannot be compromise. Irreconcilable understandings of right and wrong are at play,” it seems like a nice thing he’s got going on here. Except of course, that we’re talking about that Tim Busch who runs the Napa Institute, runs an annual conference of hard-right Catholics complaining about how Antifa is coming for the devout, and has political donations that are all a matter of public record including for the period when he was apparently hosting these fun get-togethers. From a financial perspective, Busch is perhaps the single person most responsible for raising the temperature of the Catholic culture wars over (at least) the past five years. Whatever impact Busch’s swank-ass dinners may have on The Discourse, it does not seem to yet include leading Tim Busch to think “maybe I should stop donating thousands upon thousands of dollars to Rick Scott’s campaign fund, or to the congressional PAC for the party running on a platform of mass deportations”. It’s wild that America would see this piece and take it seriously enough to publish it, until you see the disclosure at the very end: “Several members of America’s staff have participated in Mr. Busch’s gatherings, including Sam Sawyer, S.J., editor in chief; James Martin, S.J., editor at large; and Kerry Weber, executive editor.” Ah, okay. He got you guys a fancy dinner and you were like “this is fun! We’ve got an open page in the magazine for next month! You should write that you did this for us and we had fun!” Idiots.

Example (good): “Quitting Time,” by former America magazine contributing writer Kaya Oakes, on her Substack, about having to stop writing for America magazine because of how embarrassing it’s getting over there (I mean, they showed up in this piece alone like four times!). “Just because a magazine has some writers you like and respect and editors you like and respect doesn’t stop it from also including some really toxic contributors who have written some downright dangerous stuff.” Oakes was referring to, among other pieces, America’s full-throated endorsement of Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett for seats on the Supreme Court (they downshifted one of those to a half-throated endorsement due to unforeseen events). As with everything Oakes writes, her piece is brilliant and angry and funny and urgent; even though it’s “just” a personal essay on how she views The Discourse, it’s obvious that we’re dealing with someone far more sincere and far more moral than Tim Busch. “The way I learned to understand how to follow my conscience out of a job in Catholic media was through one of the documents of Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes. I’ll end with a quote from that, and because I’m not writing this for a religious magazine, I’m going to change the pronouns. Because “men” doesn’t really mean all of us after all. It means the men who run things. And maybe it’s time to stop looking to them to decide how to think.”

Perhaps that final sentence is a good one to bring us to the final part of the flowchart:

In an era when we will need good, meaningful Catholic writing and art to sustain us and help us think and help us keep going, I can survey the landscape of Catholic media - not even the right-wing trash, but the mainstream stuff - and see less the green idyllic Shire from the beginning of Lord of the Rings and more the corrupted hellscape Shire from the end of Lord of the Rings7. I'd say burn it all down, but they're beating me to it all by themselves. I wish there was more reporting, more talk about the material stakes of what the church does, more meaningful and informed engagement with art and culture, more things that can articulate hope in a meaningful way, more of anything but idiot men telling us how we’re supposed to think, with or without a flowchart. I hope that this blitz through so many bad essays gets it all out of my system for a while, because I really don't want to write about Catholic media for the foreseeable future.

Plus, I'm not really in a position to fix the problem. I'm not a journalist. I don't have enough money to fund anything that would make any changes to Catholic media. But at least in the things I do write, I can stick to my made-up flowchart as best I can. I can try to offer you consolation, the message that, as Kurt Vonnegut once said, I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people don’t care about them. If we feel alone, we feel powerless. But you are not alone, and I am not alone, and I know that because of what I think through and write here and how it connects me to all of you. And if you and I are not alone, maybe I can hope for a better world together with you. Maybe I can imagine that something better with you and then want that something with you, and someday gain that something with you. And if I cannot do those things here, then for Christ's sake I will at least be an entertaining waste of time.

Dallas: not an archdiocese! I didn’t know that! They should hustle a little harder.

“Unlike today’s woke left, Tip O’Neill would ask me how I got these scars.”

I know I already referenced that review in another essay, but that’s still incredible to me. Come on.

And I like that album a lot! But what the hell do you think the lyrics “365 party girl bumpin’ that/should we do a little key, should we have a little line?/wanna go real wild when I’m bumpin’ that/meet me in the bathroom if you’re bumpin’ that” are about? The martyrdom of pinpricks?

Just so there’s no confusion: this is meant as an almost-verbatim reference to a famous joke from the movie Airplane!, spoken by Peter Graves’ character, who is attempting to sexually groom a child.

Normally these are mutually exclusive attributes.

To put it in terms the dork-ass losers at Word On Fire would understand.