Kaya Oakes: The Profane G.O.T.H.S. Interview

“...and that's why I don't have a column in Catholic media.”

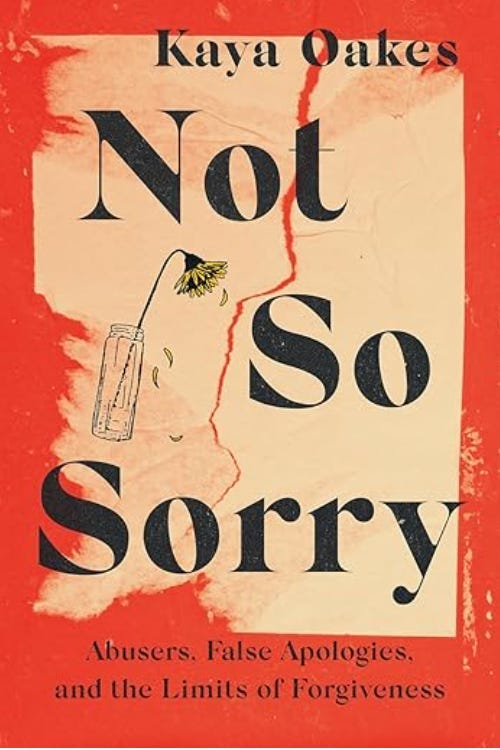

You can order Not So Sorry and find more information about it here.

Last month, Kaya Oakes published a Substack essay harshly critical of the Vatican and their disastrous communications strategies, and ended the piece with a reference to a bangin’ Kendrick Lamar track. By pure coincidence, within 24 hours, I also published a Substack essay harshly critical of the Vatican and their disastrous communications strategies (on a different thing), and it started with a reference to a (different) bangin’ Kendrick Lamar track. That's really all the explanation you need for why I look up to Kaya and consider her a kindred spirit.

Kaya's skill at engaging with the broader culture to gain a deeper understanding of what it means to actually live as a Catholic, and to meaningfully interrogate the gap between how our church should work and how it actually works, is something I admire greatly and try to emulate in my own stupid way. She remains one of the only people in Catholic media who is funnier than I am, which puts her on an extremely short list of people given the general humorlessness of the industry. Also she once wrote a book on Gen X indie culture called Slanted and Enchanted, making her one of only two theologians in history to name a book after a Pavement album, behind Saint Augustine and his landmark work Wowee Zowee. I told you I was funny!

But Kaya is not just funny and creative. Everything Kaya Oakes writes on religion is essential reading. Her writing is brilliant and insightful, which is probably why she's a contributing writer at America magazine and a writing teacher at UC Berkeley and has bylines at The Guardian, Slate, Foreign Policy, The Washington Post, and On Being. But on top of that, she writes about topics that nobody else is covering: her new book, Not So Sorry: Abusers, False Apologies, and the Limits of Forgiveness, arrives on July 24 and is a powerful challenge to common Christian and cultural assumptions about forgiveness, who can grant it, and who gets to have it. It is very much of a piece with her previous book, 2021's The Defiant Middle: How Women Claim Life's In-Betweens to Remake the World, which explored and challenged the narratives that culture and Catholicism liked to build around heroic and holy women. Not So Sorry arrives after years of watching awkward and forced and insincere institutional apologies, from our church and from others, in response to multiple abuse reports and protests against racism and countless PR missteps; this book meets the moment very effectively. There is just a lot of Catholic writing, both in choice of topic and handling of that topic, that feels trite and desperate to confirm what the reader already thinks; Kaya's writing, in contrast, is mature and confrontational and original.

Earlier this month, Kaya and I jumped on a call to talk about her new book (and some other stuff). The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity.

TONY GINOCCHIO: What is Not So Sorry, and what made you want to pursue the project and start writing it?

KAYA OAKES: The first essays I wrote, that became of seeds of this book, were written around 2019. So that's post-#metoo but post-Trump, but also pre-a lot of the more #churchtoo stuff that's come out, not just in the Catholic Church, but in the Evangelical or Southern Baptist churches, et cetera. So the writing was sort of in this space between #metoo in particular, and then just watching a lot of really shitty apologies being issued, and wanting to figure out why we're so bad, as a culture, at apologizing.

So I started writing about it, and then I got a column at The Revealer; that was where I really started to write full-time about forgiveness. It's been an arc of following this story: how do we apologize? And why are we so bad at it? And then also, what are we seeking when we ask for forgiveness, collectively and individually?

I’m glad you mentioned the timing, because there is this big stretch of time between “you start writing on this topic” and “the book coming out”. There’s even a big gap of time between “the book is done” and “the book coming out”; I had a proof of the book back in March and it’s coming out in July. In that time, even in the past four weeks, you’ve put out multiple essays [like here or here or here] on forgiveness and on very relevant things still happening in the culture, happening in the Catholic church, on the topic of forgiveness. If you were starting the book from scratch, do you think your overall message would change? Would there be anything different about it? Or would it just be, you have a whole lot more examples now of what you’re talking about?

It’s funny, because my mom, who’s in her eighties, she follows my work - as your mom does - and she said, “oh, I'm just seeing so many things about forgiveness right now! You're always ahead of the curve!” and I'm like, “Yeah mom, thanks. Yeah, that's the problem.” I wrote that book about religious disaffiliation and “nones” [2015’s The Nones Are Alright] that came out a while ago, and now there are a ton of books about that. And there are a ton of books coming down the pipeline, even another book from Broadleaf - from the same publisher I have - about why people shouldn't forgive people; it's written by a psychologist.

I think if I had written the book more recently, I'd have a lot more examples to pull from, but I do think that what interests me now is how pop culture is eating and spitting out forgiveness in really oversimplified ways. I've been writing about TV shows, and just when I see something that deals with forgiveness, I'll just throw something out on the Substack about it, but it's interesting to me how much media is still kind of consumed by this topic. It is having a moment.

You reference a few cultural depictions of forgiveness early in the book. You talk about War and Peace in the book, and then - one of my favorites - you reference [landmark 2003 Korean action film] Oldboy as a cultural depiction of revenge. First of all, any work of theology that references Oldboy is gonna get an A-plus from me. You say the contemporary culture is eating the topic of forgiveness - how do you see it depicted? What do you think it’s lacking?

In the most recent things I've seen, like the Hulu show Under the Bridge, which is based on a true story and the thing with the Pope using, ugh, [tries to pronounce frocciagine]. I don't know. My Italian did not-

The pronunciation is the least baffling part of the story for me.

The time I spent in Italy, we didn't cover that word, even though I was at the Vatican, so I'm sure people were saying it [laughs].

So with those two examples: Under the Bridge is a TV show. Big Hollywood actors, high production values, et cetera. It was taking the concept of forgiveness and really oversimplifying it, to the point where - spoiler alert - a character forgives the murderer of her child, and it takes one scene. And in real life, these people are Canadian, they went through a restorative justice process, so: months and months and months of meeting and talking and having intermediaries. So that ending was really kind of frustrating because it left out the whole idea of forgiveness being an ongoing thing, and the fact that the mother may have actually struggled to get to that point of forgiveness.

And then with the Pope stuff, the fact that he apologized [for using a slur] and then did it again. It was just a reminder that, a lot of the time, the apologies are just an asking for forgiveness knowing that it's pretty likely to happen again. I always think about the weirdest year of most of our lives, 2020, right? Because we had Ben and Jerry's apologizing for slavery and corporations like Target saying “black lives matter”. It was just so surreal to have corporations pretending to be people. Again, what’s missing there is any actual atonement or restitution or process. It’s just these hollow PR moves; “we're gonna get in trouble if we don't apologize, so we’d better”.

Something that this book does very well is interrogating these very tidy or simplified narratives of forgiveness. I think The Defiant Middle was great for exactly the same reason; it was taking a lot of these assumed narratives and poking at them very effectively and thoroughly. And at the beginning of Not So Sorry, you share this story, where you’re writing a piece for a Catholic magazine and it’s on the topic you were just discussing, “forgiveness in the age of #metoo”, we have abusive behavior in the church, how should people who have been harmed by the church grant forgivness? As you tell it, you put a piece together, you submitted it to the magazine, and they didn’t run it. What piece did you write, and what do you think this magazine actually wanted to see?

It was later published at another site, so it did have a second life, and some of it is remixed in parts and pieces in the book. The thesis of the original piece was pretty much the same as the thesis of the book, which is that we don't have to forgive everyone everything, and in fact, if we do, that can enable abuse. The editors of this Catholic magazine came back, they had had an editorial committee meeting about the piece, and decided that it was “anti-Christian”. That was the phrase that they used, in the sense that the refusal to forgive somebody is antithetical to what Jesus tells people to do. And so I just kind of went “okay, I'm gonna pitch it somewhere else”, because that's what you do when you're a freelance writer, if a piece gets killed you just send it somewhere else. And it did get published, and then that got the attention of an editor [for the book deal], so the whole thing ended up with a happy ending.

Later, an editor from that magazine subsequently left the magazine and we’ve talked about this, and I think others on the editorial board just really didn't want to rock the boat. And that's often, unfortunately, the case with our Catholic media: they don't want to get into trouble, so they’ll make editorial decisions that are a little sketchy sometimes.

Obviously, we’re just speculating, but were they really assuming that they were getting a piece that was just like ‘yep, if you’re a victim of abuse, get ready to forgive!’? Or something like that?

They knew I was interrogating apologies in the wake of #metoo, because that was around that time, and interrogating hollow apologies, and tying it in to the sex abuse crisis in the Catholic church. But along the way I found scholars, many of whom happened to be ordained Protestant women, which might have been part of the problem; one of them is a woman named Marie M. Fortune, who runs a whole institute on forgiveness. These scholars were arguing that we don’t have to forgive everyone everything. Again, because they’re ordained, I think it was making Catholics nervous [laughs].

Continuing to talk about the Catholic church: chapter five of the book is subtitled “how the Catholic church lost its right to forgiveness”, referring mainly to clergy sexual abuse and the institutional coverup. You observe this in the book, and in other writing you’ve done, and I’m seeing it every day too: do we have any reason to believe the church is sorry, at all, about basically…anything?

[Laughs] Ever? It’s hard, because I think it’s the classic Janus face - and I’m sure I use that phrase in the book, I grew up watching Janus Films because my dad liked art movies - where in one way, the church is sorry, because you can’t have that legacy of the missions and colonialism, crusades, just everything, and then up to the twentieth century sex abuse scandal, which is obviously still ongoing. They are sorry for it, but a lot of the apology for it is caught up in the loss of people, loss of money, loss of seminarians. We just lost the Paulist fathers in Berkeley; after a hundred and seven years, they just had to leave their church here because they don’t have enough priests to staff it, and that’s a common story in every diocese - priests are doing four or five churches in a Sunday - and that’s because of the sex abuse crisis. And there’s a sorrow about that, but I’ve heard too many homilies about how priests accused of sex abuse should be given a second chance. Like, I’ve heard preaching on this!

Jeez.

So, I think I just, sort of feel like…no, they’re not sorry. And, you know, anyone who’s seen The Keepers or Spotlight or anything knows that this is still very much an open wound for people who were abused. Another friend of mine, he was at a monastery, he was young, a good looking guy, and some of the older monks were kind of like, coming on to him, and so he left. He abandoned his vocation because it was uncomfortable, and he was like “I don’t know who to tell, the abbott’s aware of it,” so it’s just an unsolved problem.

So the church is sorry, in that it’s weakened the reputation of the institution and exposed a lot of power dynamics that were very problematic. But are they sorry enough to sell everything and give it to the victims? No.

I think throughout, really, all of your writing, I can find a lot of anger at things like institutional inertia, at easy narratives or easy answers, trying to get out of tough conversations, things like that. And it’s good anger, anger that I admire and try to emulate in my own writing, it’s focused, it’s righteous, it’s pointed. Why is it important to you to write about the things that make you angry?

I feel like when I came back to the church…I came back as an adult, so I had my little hiatus, my rumspringa, which went on for quite a while. In that time, I did a lot of social justice work, a lot of activist work with people who are poor, people who are marginalized, and it just felt like I brought that back with me. Actually, the priest who ran my RCIA group for returning Catholics, he told me “that’s why you’re here. Here you come, with this skill set and this background that other people don’t have, and that’s why you showed up!” And I was like [kind of baffled voice] “okay” [laughs]. Of course he turned out to be right, he was a wonderful guy.

I think that culturally, anger is sort of reserved for January 6th rioters, and when we take that back from Christian nationalists - and, in the Catholic church, I would say trads, that kind of community - they’re very furious all the time about all of these perceived slights. Oh, you can’t have your Latin Mass? My gay friend was denied ordination, or this church that I go to doesn’t want to feed homeless people anymore because they end up sleeping on the sidewalk outside, and that looks bad on Sunday mornings. So I think we need to reclaim that anger. It’s a lineage in our tradition. Dorothy Day, Daniel Berrigan, Cesar Chavez…Jesus [laughs], these are angry people. And anger can be a fuel for justice work. For me, that’s how I see it, and it’s part of my job as a writer in general, and because I write about religion, it’s always going to be tied up in that.

The flip side of that, of course, is that your writing is often very funny, which I really appreciate-

[Interrupts] Not as funny as you, Tony, come on-

[Interrupts] That’s very kind, I’ll make sure I include that in the write-up [laughs]. This book, less so, this isn’t meant to be funny. BUT, when I look back at [your 2012 book] Radical Reinvention, you describe your writing as “heavy on irony and sarcasm, laden with self-effacement, and frosted with a layer of bitterness.” I love that you have an appreciation for what humor can bring to your writing, especially if you’re writing about something that pisses you off. What role do you see your sense of humor playing in the work you do and the way that you see your faith?

It disarms people. They’re prepared for, you know, “oh God, here comes this rant, this feminist rant, she’s from Berkeley, Jesus Christ, he we go,” and then when it’s delivered with a sense of humor, people are unprepared for that. I think people think you have to be kind of dour to talk about serious topics. I’m not going to become Dave Chappelle, you know, I don’t believe in punching down, but I do believe in punching up, and sometimes the most effective way to punch up is to make people laugh at somebody who deserves it. Like, your jokes about Bishop Barron always make me laugh.

Thank you…

He’s so pompous and so full of himself, and also very toxic, a very bad person in a lot of ways, and if we poke holes in people like that with humor, we can kind of deflate them a little bit, and take them down to a size where we can say “okay, now the joke’s over, let’s talk about the real problem with this guy”, right? I feel like that approach is very effective. I grew up here, around people like the San Francisco Mime Troupe and the Diggers, and the counterculture, and zines in the 80s - I was a punk, so zines were a big part of my life - they used humor to attack the power structures - I still love Abbie Hoffman, when they tried to levitate the Pentagon - and then it was culture jamming, and so on. And that legacy, I think, is not present in religious circles as much as it should be. I would love to see more of that kind of sense of humor brought to stuff like Catholic Worker houses, but they’re just so busy [laughs]. They don’t have time. I think for a lot of writers I admire, humor is a way to poke holes in people’s egos who deserve it.

Related to that: another word you use to describe your writing in Radical Reinvention is “profane”. In the context of the book, you're saying you swear a lot and you're not deferential to authority. And throughout that entire book, every time you meet someone else who is similarly foulmouthed or can easily criticize church leadership, you're like “ah ok, this is someone I'm going to get along with”. There are a lot of times when I have felt the same way; I think it’s part of why you and I were able to connect with each other. What do you see when you see a Catholic being “profane” that gives you that sense of “this is someone I’m going to like”?

I think it’s like a “game recognize game” thing, this recognition of “why are we taking this so seriously that, I don’t know, we can’t say ‘shit’ or ‘fuck’?” I imagine that, again, Jesus was running around with prostitutes and fishermen. I don’t know how people swore in Aramaic, but I imagine He heard that kind of thing, and the idea that he was this prissy, prudish, above-it-all guy…even His mom, obviously, was not fitting in with the common image of women of her time.

Language is a really powerful thing, and profanity has a purpose. It’s cathartic, it’s funny. I think that’s recognizing other people using it, not just to shock, but as a form of sincere self-expression. When I taught at the Jesuit seminary in Berkeley, sometimes I’d take the class out to dinner or have them over at my house, and it would just be like [string of profanity], and they were just releasing all of their built-up stress and anxiety. Every priest I’ve ever met, behind closed doors, is just like [another string of profanity], just letting off steam, and I think that’s healthy, but there’s a place and a time for it, I’m not trying to say-

[Interrupts] “Kaya Oakes Gives a Blanket Endorsement of Swearing at All Times”.

[Laughs] I’ve been to some Protestant churches where they’re trying to be really hip and cool and like, they’ll drop an f-bomb in the sermon or whatever and I’ll be like “yeah…you’re trying a little too hard, buddy.”

You brought up Robert Barron, who’s a guy I have made fun of a lot, and I’m not going to pass up another opportunity to make fun of him. But the reason why I think he makes for such an easy target for the kind of stuff that I do is because I think he uses this image and mystique of his office to buttress his power and his sense of authority. When, really, he’s just posting online, and it’s very obvious from what he posts online that he’s not a very discerning media consumer, right? And so, I think that what you said is exactly right, we tell jokes to disarm people and to poke at people who take themselves really seriously, but I think that seriousness can be a real source of power sometimes. To puncture it by laughing at it can be valuable. To puncture it by being less formal than, perhaps, might be expected when dealing with that office, can also be very valuable.

What was his line? Jordan Peterson is reaching young people today or something?

Yeah, basically, reaching young people and “nones”, specifically, was the whole thing.

And he has clearly never had a conversation with somebody who doesn’t go to church. Everybody who works for his institute is completely church-mad. The fact that he knows so much about this group of people that he’s never interacted with? It just drives me batty, I can’t stand that. So I think, again, it’s about deflating people, taking them down a peg, and also it’s a way of expressing discontent or anger that doesn’t hurt people. Satire doesn’t hurt people…I guess, unless you’re the target of it. But I’ve had some satirical stuff written about my work by right-wing trads, but I just think it’s hilarious because it’s never very well-written.

Yeah, I got called “whiny” once by someone else on Substack, but honestly it was a good note.

Nice [laughs].

You’ve also written before about why you write at all, and what success means to you as a writer, and what it means to you to reach someone and have your writing mean something to someone else, even if you are not one of the “popular kids” in the publishing world. That particular piece I found really wonderful, and I would also say I’m not on a trajectory where I’m going to become a bestselling author. Why do you keep writing, and what are the things that, when they happen, make you feel like you’ve succeeded as a writer?

Well, first of all, you never know [laughs]. There are books that have become bestsellers…there’s a guy here in Berkeley named Adam Mansbach, he wrote a children’s book called Go The Fuck to Sleep-

[Interrupts] I remember that!

It sold so many copies. That book? Okay!

For me, I’m at this juncture of life where I find myself having to start all over again with a bunch of stuff, and that includes freelance writing. The writing I’m doing now with Substack, that’s where I’m working out ideas, right? That’s the rough draft, here are some things I’m thinking about, here are some things I’m considering. I gave up my column because it’s the end of the road for me writing about forgiveness, the book is kind of like…do I want to keep writing about this topic in the future? No. I’ll keep writing for The Revealer, but that column has ended.

So I don’t know what I’m going to do next, and I’m kind of enjoying that, actually. I’m just in a time of exploring ideas. I need a break from writing about religion, but religion’s always going to be part of things that I write, so I need to figure out how to navigate that. For me, the best relationships I’ve made…I think I’m very lucky in that I don’t have a huge readership, but I have people who follow what I write, so as a result of that, I’ve actually become friends with some of those people. I actually feel like we have a kind of kinship, and when you’re really famous, I don’t think you get that. Like, one time I tweeted at Colson Whitehead, and he replied, and I was like so excited, right! But he gets that five thousand times a day. But is he ever going to have an in-depth conversation with someone like we’re having now, just because they read his book? So I feel very very lucky to have the career that I have, and I don’t take it for granted at all. I didn’t publish my first book until I was almost forty; that’s not the trajectory that most people want to be on, but it’s mine, and it worked out.

I am always, always, always so grateful that I have been able to connect with you, to talk more about your writing, so thank you again, I just have nothing but gratitude for the work you do, for the writing you do. So much of Catholic media, even outlets that I enjoy reading, feels like it is on training wheels and running the same opinion column over and over and over again, and I feel like your work is so original and mature and grown-up, and I really just…I am very grateful.

Thank you. And that’s why I don’t have a column in Catholic media [laughs]. But I really appreciate it.

And, also! You’ll appreciate this, I was thinking about Sabrina Carpenter today.

Well, she’s got that “Espresso” now-

What is “that’s that me espresso”? What does that mean?!?!

So, it’s very simple! The point is, this guy is thinking about her all the time, so much so that he can’t sleep. She’s having the same effect on him that drinking an espresso would. That’s that her espresso.

[short pause] That’s that me espresso…

Grammatically, it’s not perfect.