Failure and Splendor

You get two essays on Romero this week, but one of them has to also be about 1970s comics.

Recently, as a gift, I received a copy of the book of Genesis as adapted by legendary underground comics artist R. Crumb, the man who pioneered all sorts of weird drug-addled hallucinogenic comics in the sixties and seventies. For example, Crumb created the character of Fritz the Cat, subject of the first X-rated animated film ever made. So yes, this adaptation, from 2009, was a little different than the fancy Alabaster Bibles thing you see ads for on Facebook.

The contents of the book of Genesis are extremely well-suited to Crumb’s style, however, because the stories in Genesis are weird and trippy and full of magic swords and incest and weird giant monsters called nephilim and a lot of stuff that never makes it into the lectionary tables. Crumb called the first book of the Bible “a text so great and so strange that it lends itself readily to graphic depictions”, and went with very literal interpretations of the King James and Robert Alter translations, for an extremely strange and fantastical reading experience. He's not a believer, but also did not want to bring his usual satirical edge to this project, which he says he treated as a “straight illustration job”, and the results are bizarre and wonderful.

A less thrilling part of Genesis - although Crumb also depicts it - are all of the genealogies throughout the book, long lists of who begat who and how long they lived. You have to wonder how those people, those names, scored that prime placement. Their names are written down forever, in the most read book of all time. We don’t remember anything else about them, but that name is there and it’s never going away. Whatever they did mattered a lot, whenever they did it.

So you get two essays on Oscar Romero this week, as we hit the four-year anniversary of his becoming a saint. You can’t really top the four pastoral letters we covered earlier, but I do want to take a minute to think about his final homily, delivered in March of 1980. Like I said in the essay earlier this week, Romero didn’t “win”. He had an incredible vision of how the church could participate in the liberation of the poor, but he did not live to see the poor of El Salvador liberated from violent government oppression. If “success” is defined as “material conditions getting better for Salvadorians” or even "the murder of Salvadorians by their government slowing down somewhat", Romero failed. If you admire Romero, if you are blown away by his vision for the church, you still have to reckon with the fact that he didn’t get it done. Romero’s final homily is a response to that scary question: what happens if we fail?

Romero did everything he could for the people of El Salvador, and the people he served did everything they could to organize each other. All of them must have wondered if it was going to be enough, as violence continued to burn across the country and more people got murdered. Maybe the bad guys were going to win. Maybe what we were trying to do wasn't going to be enough to make our situation better. Maybe we were doomed. But Romero used his final homily to drive this point home: we don't get to determine whether or not we've failed in our efforts at liberation. What we do to attack the structural causes of suffering, we do without ever seeing the full effect. We do it without getting the reward of seeing how successful we've been. We can't do everything, and we may not see the full impact of what we do, but we can do something, right now, and that something is blessed and encouraged by the God who liberates. It was and is a beautiful message.

And then the message got driven home a little too well, because as Romero was wrapping up this homily, he was murdered.

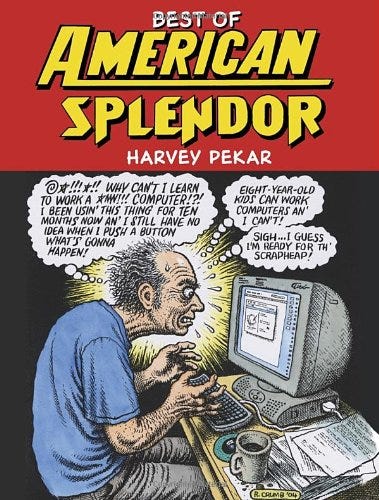

If you were to page through the underground comics at your local 1970s smoke shop, you'd find all of those weird Crumb-like hallucinogenic depictions of characters fucking and performing acts of gratuitous violence and using all sorts of foul language, uncensored and deliberately provocative stuff inspired by the countercultural movements and drug culture of the era. And then you might also find a comic about a balding man in Cleveland just trying to do his job and be a good person. That one is Harvey Pekar's American Splendor. Here’s one with a cover by R. Crumb:

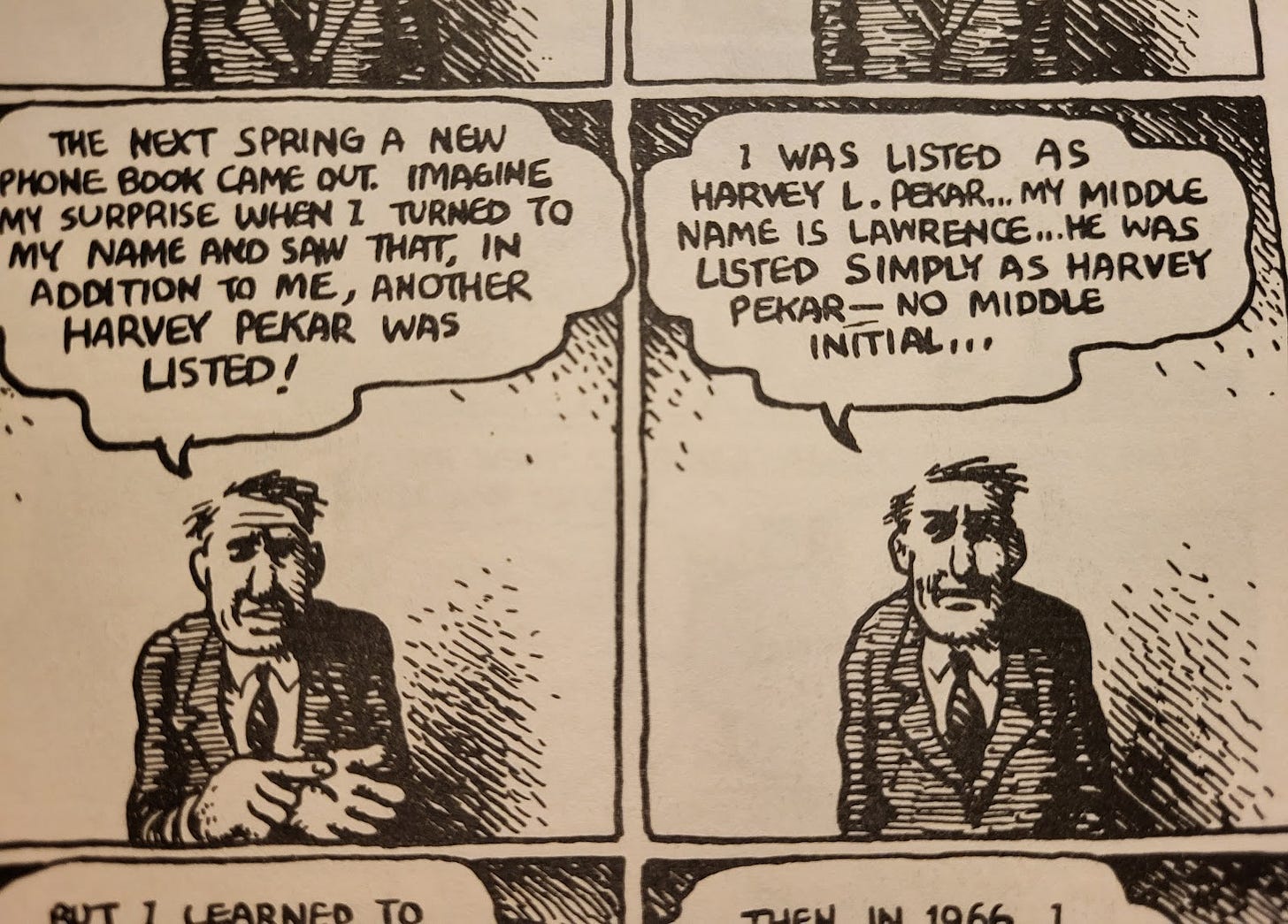

Pekar did not invent slice-of-life autobiographical stories, of course, but it is pretty remarkable how few things actually happen in American Splendor comics. Sometimes Harvey goes to the store and stands in line to check out. That's a whole issue. Sometimes he goes to the store and also comes back. That's another issue. Sometimes he gets a ride home from work. Sometimes he buys a jazz record and goes home to listen to it. The most exciting plot in the first two decades of Splendor is when actor Wallace Shawn visits Cleveland once as part of the publicity tour for My Dinner With Andre, and Harvey gets to ride in a car with him. In many - many! - comics, the only action is Harvey looking out of the frame directly at the reader, talking in a phonetically-written Midwestern accent to deliver a monologue on a high-stakes pulse-pounding issue like "once I found another Harvey Pekar in the yellow pages” (shown below, also illustrated by R. Crumb).

And yet, these seemingly uneventful stories are, well, splendid, mainly because of who Harvey is, as a writer and as a character. Working against most of the stereotypes of "work of literature where the main character is a contemporary white male writer or other obvious stand-in for the author", the character of Harvey is not a misanthrope, he's not smarter than the people around him (and he knows it), and he's not paralyzed by modernist existential dread and ennui. He is a guy who is going to work every day and honestly trying to be a good and helpful person to the people around him. Not that Harvey is a saintly figure; he avoids confrontation for longer than he should, and he's more brusque with his friends than he has to be, and sometimes he beats himself up more than he needs to, and by all accounts he's an unbelievable slob, but overall, he's a guy who wants to be there if people need him, who is always riveted by those people's stories - and his own - and who thinks those stories, no matter how quotidian, are worth telling and learning from.

These stories, which Pekar would outline panel-by-panel with stick figures, were handed off to some of the biggest artists in the underground comics movement, including Crumb, to illustrate. As Crumb put it:

"What Pekar does is certainly new to the comic book medium. There's never been anything even approaching this kind of stark realism. It's hard enough to find it in literature, impossible in the movies and TV. It takes chutspah to tell it exactly the way it happened, with no adornment, no great wrap-up, no bizarre twist, nothing. Pekar's genius is that he pulls that off, and does it with humor, pathos, all the drama you could ever want…in a comic book yet!"1

Crumb, who illustrated most of the early issues of Splendor, was already established in underground comics before working with Pekar, and got connected with Pekar because, well, they lived down the street from each other at one point. It wasn't through any of Pekar's professional connections in the comics world, because Pekar didn't have any; as Crumb put it, Pekar was "in total isolation from any comic-publishing 'scene'...I'm fairly certain that the sales of his comic books have never covered the printing costs."

That's the other thing about American Splendor: it was, eventually, a modest commercial success, since Pekar started selling stories to DC and Dark Horse. In 2003, American Splendor became an Oscar-nominated movie where Paul Giamatti played Harvey (Pekar himself also played Harvey; the movie had a very meta sense of humor). But, for decades, American Splendor didn't make money at all.

I find American Splendor to be really beautiful storytelling in its exploration of the everyday, but part of what makes it work was that Pekar's "everyday" was a lot closer to your and my "everyday" than it was to the "everyday" of a famous author, or even an established author. Pekar self-produced, printed, and published Splendor himself for 17 years; he got stuck with boxes of back issues in his tiny apartment. Throughout this period, he consistently lost money on the project. He did some other freelance writing, notably as a jazz critic for Downbeat, to make some extra money, but more importantly, he didn't quit his day job. Even as his comics were picking up buzz and attracting more artists to illustrate more stories, Pekar kept taking the bus to work full-time as a file clerk in a VA hospital. In the commercial sense, Splendor was a clear failure, and Pekar kept writing it anyways.

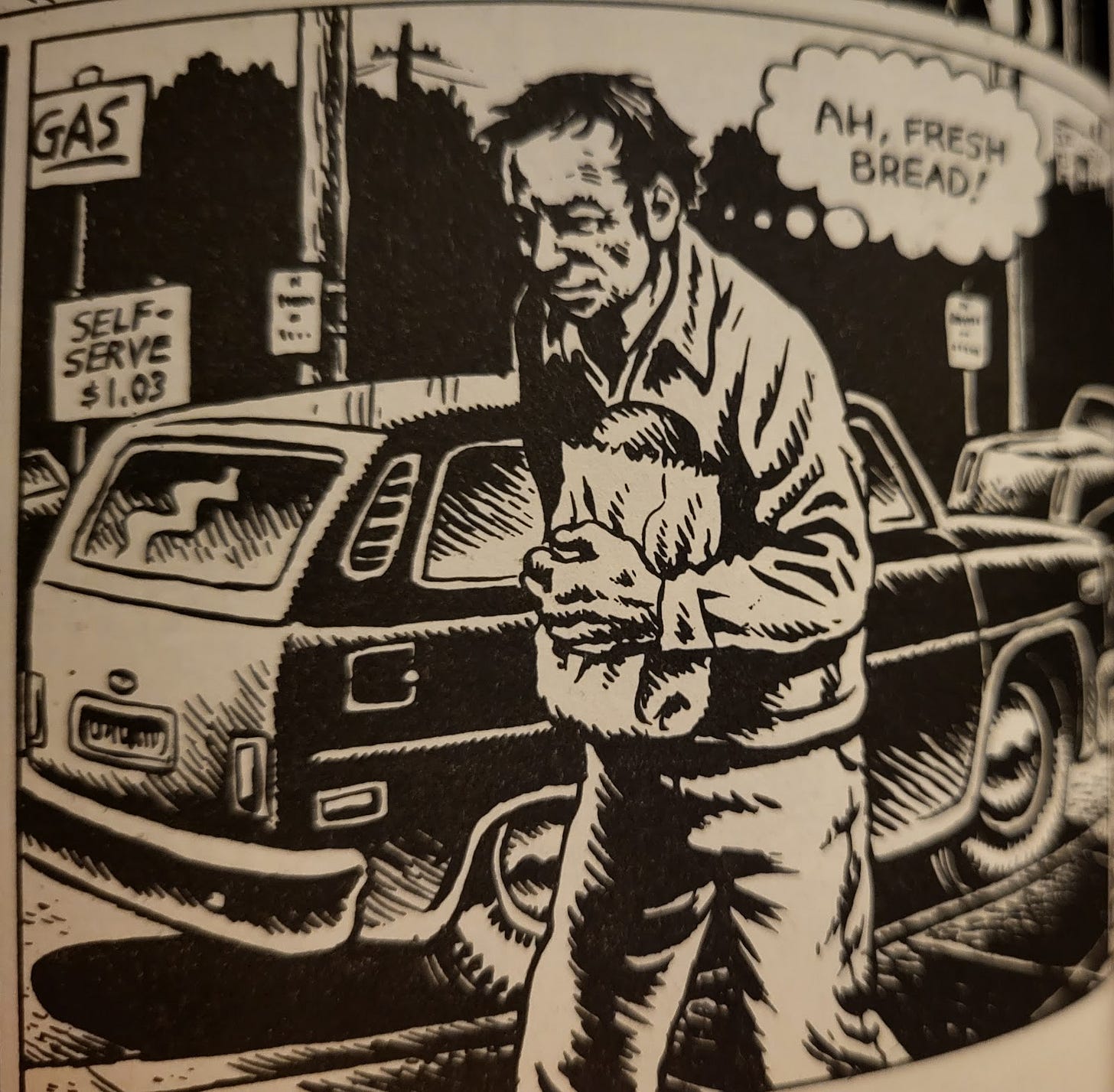

Was Pekar resentful that he had to keep working at his job instead of being able to dedicate more time to Splendor? Not really, based on his writing. Repeatedly, the character of Harvey expresses his relief that he has his very stable job with the federal government, and more importantly, he's not really sure he'd be as good a writer, or if his writing would matter as much, if he wasn't working in that job. He wouldn't be able to tell his stories about slowly navigating a rocky friendship with the guy who drives him home from work, or finding a great pair of old shoes at the thrift store and turning his day around, or deciding and legitimately trying to be less grouchy at work. Here's Harvey's inner monologue as he walks home from the bakery in a Crumb-illustrated issue from 1984, eight years after Pekar had started writing Splendor:

"It’d be nice not to have to get up ev’ry morning and go to work, to be able to read or work on stories and articles whenever I feel like it. But then I’d sort of be out of the struggle, sort of in an ivory tower watching the mainstream of life go by rather than participating in it…I’d be alienated but I wouldn’t think I had the right to feel bad about it. I mean, I’d be a well-paid, famous author. What right would I have to complain about anything? Maybe my writing would suffer…If I lived a different life I could still write about it. But would it be as interesting a life?”

And Harvey doesn't answer that question, but at the end of this comic, he opens the bag he's carrying, takes a sniff, and says "ah, fresh bread!" What matters to Harvey the character, and what matters to Pekar the author - and there's really no daylight between the two of them - is being in and speaking to "the mainstream of life", is finding joy in the immediate, is being there to help the people around you and let them find joy. Success and failure have nothing to do with scale, and certainly nothing to do with whether or not you feel successful.

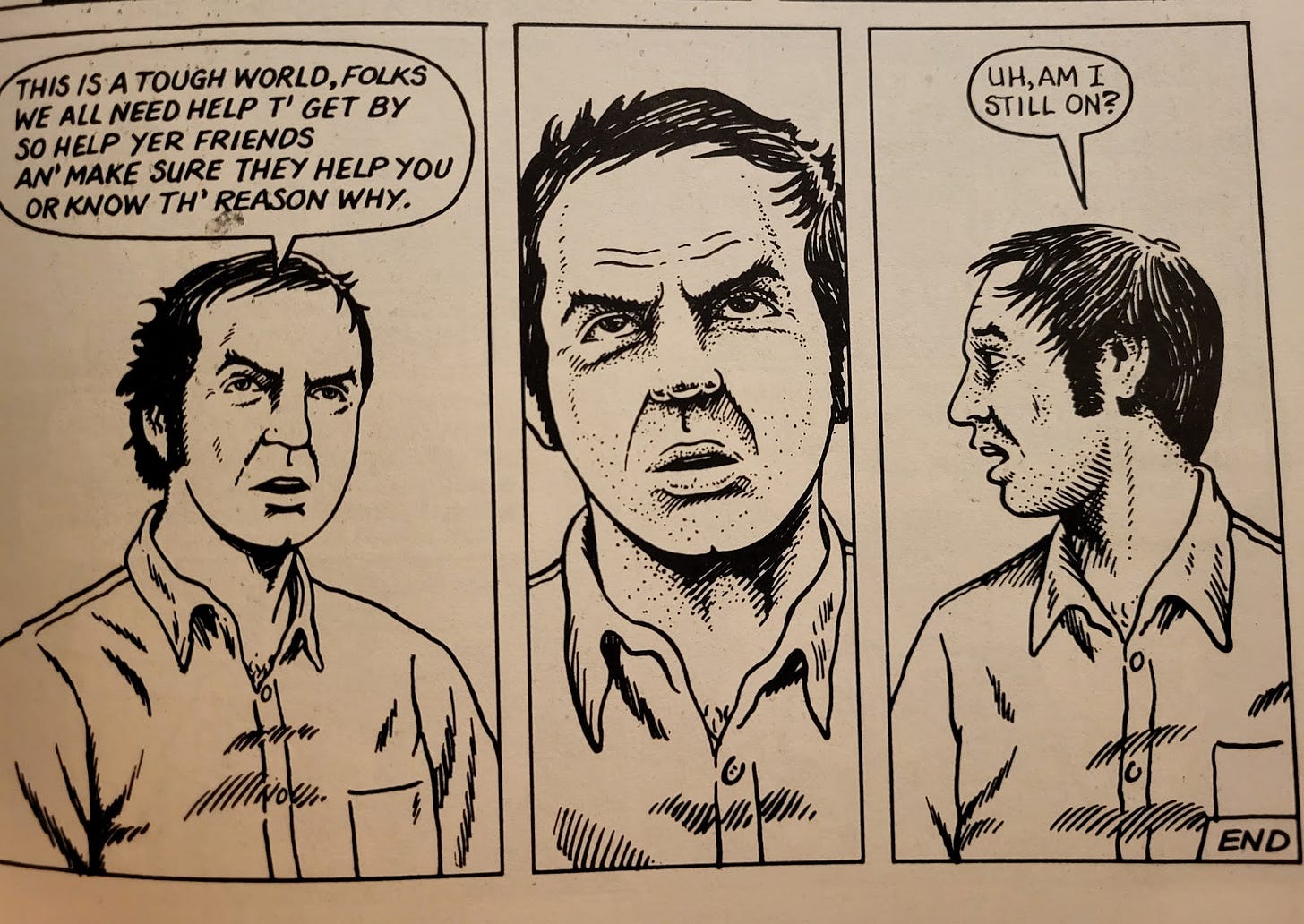

For Pekar, success and failure also had a lot to do with whether or not you tried to help the people around you. In a 1981 issue not-subtly titled "READ THIS", illustrated by Greg Budgett and Gary Dumm, Harvey meets a new acquaintance through a friend, and they mainly trade old jazz records a few times without forming a close friendship. It's a mostly transactional relationship, and that's fine.

But one day, the new acquaintance is getting kicked out of his apartment and desperately needs someone to help him move. Harvey doesn't want to do it - he barely knows the guy and moving sucks - but nobody else is going to do it, and Harvey figures he doesn't have any choice but to help the guy. So he does, and the move goes fine, and time passes. Soon enough, Harvey has to move into a new place, and he's got a lot of jazz records to load into his car. Every single one of Harvey's friends bails on him and doesn't help with the move, and who can really blame them, moving sucks. But the one guy who shows up to help is the casual acquaintance that Harvey barely knows, that doesn't even get named in the comic, but Harvey helped him move once and now he's back to return the favor. And once they start moving, the action cuts out and Harvey, against a blank background, starts addressing the reader directly [emphasis Pekar's]:

"There’s a lesson in this. Nuts to the so-called friends a’ yers who grin in yer face but ain’t there when you need ‘em. People like that are a dime a dozen. Friendliness is not one of the first things I look for in a friend. The most important things are honesty an’ reliability. Gimme a sour-faced buddy who returns phone calls, shows up when he’s supposed to, an’ pays his debts when they’re due. This is a tough world, folks. We all need help t’ get by. So help yer friends an’ make sure they help you or know th’ reason why.”

I don't know how much more bluntly you can deliver your message than commissioning a drawing of yourself looking out of the paper towards the reader, saying your message in bold letters, and then titling the whole thing "READ THIS". LIFE IS HARD. HELP PEOPLE AROUND YOU. IT DOES NOT MATTER WHO THOSE PEOPLE ARE OR WHY YOU ARE HELPING THEM OR IF YOU ARE A GOOD ENOUGH PERSON OR WHETHER YOU FIX ALL OF THEIR PROBLEMS TODAY, JUST HELP THEM. A VA file clerk who never went to college, who dreamed of becoming a writer and for years sat on crates of his own self-produced comics to eat cereal for dinner, figured this out. Pekar did not measure the successes or failures in his life by how many comics he sold or how respected he became as a writer - what respect he did get came very late in his writing career - or if he could achieve any sort of life beyond "guy who went to work every day". What was important to Pekar was that he was able to be a good person to the people around him. Not that he could change the world or be recognized for his brilliance, but that he could make the life of the person next to him a little less hard. Doing that matters, and it matters right now.

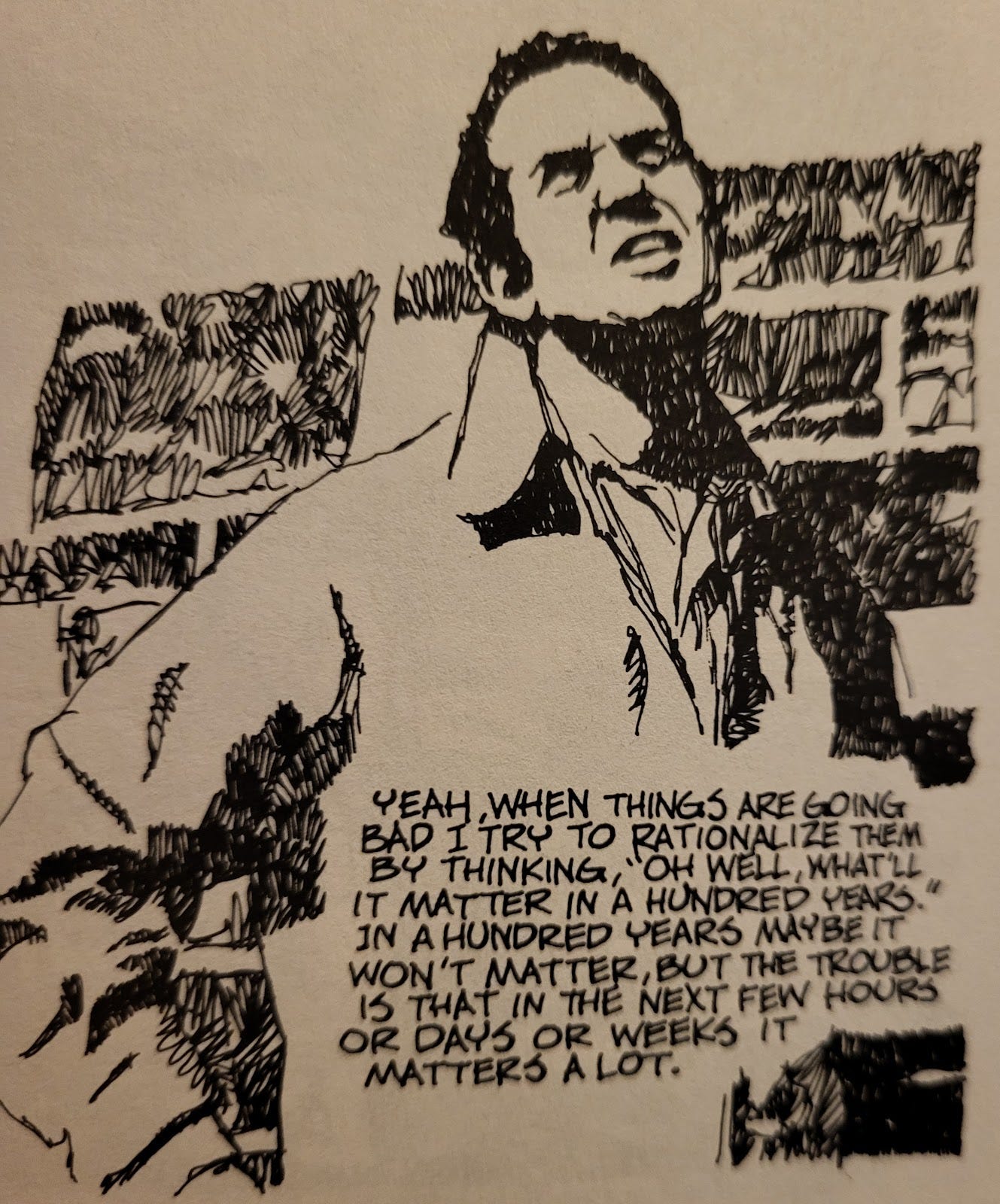

There's a 1983 comic titled "I'll Be Forty-three on Friday (How I'm Living Now)", illustrated by Gerry Shamray. The entirety of the action is Harvey walking around a park, thinking to himself, and at one point he goes here:

"Does it matter if you’re happy or sad? I mean a human life span is so short compared to eternity, a human being is so insignificant compared to…well, I take that back…absurd as it really might be to believe it, we really think we're very important, regardless of how insignificant or short lived we are. After all, we're the only ones living in our heads and in our skins. Yeah, when things are going bad I try to rationalize them by thinking 'oh well, what’ll it matter in a hundred years.' In a hundred years maybe it won’t matter, but the trouble is that in the next few hours or days or weeks it matters a lot.”

Pekar wasn't ever going to save the world, and while American Splendor eventually found some modest success, it's unlikely that you've heard of it unless you were already into underground comics. Does that make Pekar a failure as an author or a person? He helped a few people - not a lot of people, but somebody - get by in a tough world, and he helped them in a way that maybe wouldn't be remembered a hundred years from now, but that definitely mattered over a few hours or days or weeks. Maybe success and failure have nothing to do with scale, and maybe it isn't up to Pekar - or any of us - to determine on our own whether we've succeeded or failed.

I have decided to bet on something other than boredom and cruelty. That bet requires me to recognize and respond to the suffering in front of me. That suffering has material root causes that can be addressed. And what I do now, with the people around me, to address those causes matters, even if it doesn't solve the problem completely, even if it doesn't solve the problem on a large scale, even if it doesn't solve the problem in my lifetime. I can still do something that matters, even if it is just being there to make the life of the person next to me a little easier. We should push ourselves to address the root causes of the suffering in front of us as best we can, but it is not up to us to decide that we were failures because we didn't do enough. So let us do what we can, because we can all do something.

I can't take credit for that last sentence, that's from Oscar Romero's final homily.

"Dear brothers and sisters, let us all view these matters at this historic moment with that hope, that spirit of giving and of sacrifice. Let us all do what we can. We can all do something, at least have a sense of understanding and sympathy."

It wasn't long after Romero said these words that El Salvador would descend into civil war. More immediately after saying these words, Romero would be shot at the altar and die while being rushed to the hospital. He did not live to see things get better. Does that make him a failure? Or did he already know that he, by himself, was never going to be the one to change everything in his lifetime? And does that make him a truly stunning model of Christian vocation?

"This is the hope that inspires us Christians. We know that every effort to better society, especially when injustice and sin are so ingrained, is an effort that God blesses, that God wants, that God demands of us…All we cultivate on earth, if we nourish it with Christian hope, will never be a failure. We will find it in a purer form in that kingdom where our merit will be in the labor we have done here on earth."

If I respond to the suffering I see in front of me, expecting that I'm going to see that suffering get fixed permanently, that I'm going to see ingrained sin and injustice evaporate, directly, because of something I did…well, that seems like setting myself up for disaster. I have to trust that whatever I'm able to do is something that matters, and that I may feel like a failure doing it, but that I'm ultimately not the one who determines whether I'm a failure.

The Mass that Romero was preaching at when he delivered this homily, by the way, was a Mass of remembrance for Sara Meardi de Pinto, who had died a year earlier, who was also involved in the struggle for justice in El Salvador, and whose son ran an important leftist newspaper in the country. She didn't live to see things get better in her country. Does that make her a failure? Or is that how we should be assessing "failure" at all?

"Even after her death, she sends a message from eternity that it is worthwhile to labor, because all those longings for justice, peace, and well-being that we experience on earth become realized for us if we enlighten them with Christian hope. We know that no one can go on forever, but those who have put their into their work a sense of very great faith, of love of God, of hope among human beings, find it all results in the splendors of a crown that is the sure reward of those who labor thus, cultivating truth, justice, love, and goodness on the earth. Such labor does not remain here below, but purified by God's Spirit, is harvested for our reward."

This is a hard lesson. If you are going to address the suffering in front of you, you are going to feel like a failure. I have tried to do this and I have felt like a failure. I have, perhaps, helped certain people at certain times, but I have never solved the overarching problems that led them to need help in the first place. The final success, if it happens at all, is not something I get to see.

But if we do feel like failures, is that a reason to abandon our efforts to help the people next to us live their hard lives? Or does what we do now still matter? Do I have to go out looking for the perfect thing to do to relieve suffering and address its causes, or can I start by doing something about the suffering right in front of me, because it’s not exactly hard to find people suffering?

It seems like the answer is pretty clear to me; the only thing that could possibly complicate things is if "helping people" happened to not feel good or comfortable, and in fact felt very bad and very uncomfortable a lot of the time. Boy, I sure hope that's not the case.

Taken from a foreword Crumb wrote for a 2003 anthology of American Splendor.