The real Chicago-heads reading this already know their Chicago trivia backwards and forwards. Who plays the prison guard at the beginning of Blues Brothers1? What event from the past ten years, if it had actually happened, would have added a fifth star to the Chicago flag2? What's the motto of the city's park district3? If Kendrick Lamar went to Superdawg Drive-In, what condiment would he ask for on his hot dog4? But here's a great one: what is the largest Bible verse in the city? Like, the physically biggest Bible verse, the surface with a Bible verse on it that takes up the largest surface area? It's not in a church or temple or mosque. It's not in a museum. Actually, it's on the back of a work of art in a building that's not open to the public, but I have to flex on all of you and say that I have actually seen this particular work of art and particular giant Bible verse.

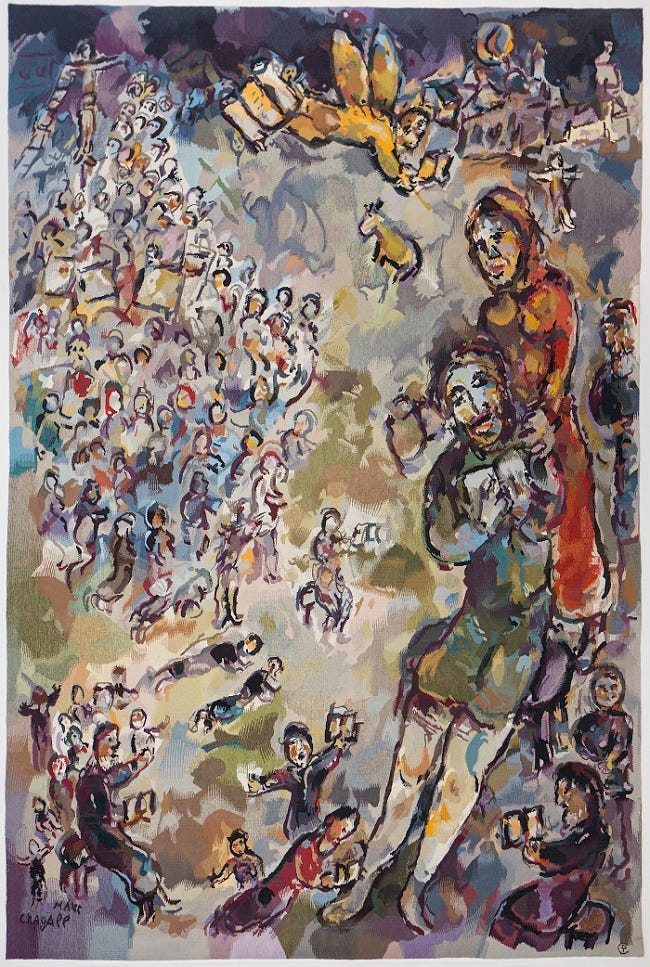

“Job” is one of three works of large-scale art made for the city, and the final commissioned artwork ever, by revered twentieth-century Jewish modernist Marc Chagall. Chagall's blue stained glass “America Windows” are a permanent installation at the Art Institute of Chicago; Ferris Bueller and Sloan made out in front of them while Cameron got lost in the pointillist Seurat painting. Chagall's “Four Seasons” mosaic is in the Chase Bank tower downtown. “Job” is a massive tapestry - 11 and a half by 13 feet - and, as you would expect, the Bible verse it bears comes from that book, specifically chapter 14: “For here is hope of a tree if it be cut down, that it will sprout again. And that the tender branch thereof will not cease.” A very powerful quote about healing and rebirth. The Biblical context is strange, though: Job, of course, is one of the most baffling stories in all of scripture, and while I'm not smart enough to break it all down for you, you probably already know that it's a story about God unleashing unbearable torments upon His most faithful follower for the reason of, and I'm paraphrasing, “fuck you, that's why” (cf. chapter 38 of Job). Even that beautiful verse about rebirth, spoken by Job in an extended monologue, is referring to a tree and not a human, since the verses surrounding that one express the sentiment that, and I'm paraphrasing again, “good thing trees can do that because when humans get hurt or die they're pretty much fucked” (cf. chapter 14). But still, the one verse by itself about the tree, that's still a nice verse, and as we'll see, Chagall has put it in a very new context.

So that's Job, the guy who said all of that, on the right side of the tapestry above, in the foreground. The woman standing over Job is his wife, who encouraged Job to “curse God and die” in response to his torments. But take a look at the upper left corner of the tapestry, shown here:

The owners of the tapestry note that:

“In the upper-left corner is a depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus. This configuration of Christ represents, for Chagall, the suffering of all mankind…Chagall made a gathering of people in the shape of an evergreen tree. In this grouping, one can see, either in a real or illusionary sense, various things used by people with functional impairments, such as a wheelchair, canes, various braces (orthoses) and artificial limbs (prostheses).”

You see, the most interesting thing about this artwork, to me, is where it's located, where a world-famous artist chose to hang Job alongside a crowd of disabled people gathering around the crucified Jesus, where people read that Bible verse about the hope of renewal every day. “Job” is hanging in the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, which was known for many years as the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, a world-class hospital assisting in recovery from everything, from traumatic brain injuries to strokes to pediatric cancer. Chagall dedicated the tapestry to all disabled people of the world.

A month ago, I wrote another essay in which I was trying to figure out why I cared about being Catholic and what I was supposed to care about in 2025, a year when it sure seemed like things would start getting way worse very quickly. I wrote:

“Gerard Way watched 9/11 happen, saw his world end, and chose to tell us that “you’re not in this alone”. Kurt Vonnegut watched the firebombing of Dresden, watched us repeat all of our bloody mistakes over and over again, and chose to tell us that “you were sick, but now you’re well again, and there’s work to do”. Corita Kent got squeezed out of her church and religious vocation in which she had lived for thirty years and chose to tell us that “the only rule is work” and “love is hard work”. There are worse messages that we could choose to listen to and let guide us into 2025.”

There’s a reason I picked those three people and not others5. They weren’t theologians; they were all artists, ones that had each witnessed different periods of upheaval and decided to respond in a way that could cut through the noise of suffering and uncertainty and passing years, and that is who I wanted to hear from.

Chagall, in his lifetime, had also seen quite a bit of suffering and upheaval. He had witnessed both world wars up close, and eventually had to flee Nazi-occupied France. At the end of his life, he made a work of art dedicated to all of the disabled people in the world, to the people that are too easily forgotten and crushed and left behind, and he hung it in a building full of people who were slowly working on their own healing, some of whom were in seemingly hopeless situations, some of whom would have every reason to just “curse God and die” and chose not to, and they are gathered around a man who, to Chagall, represented the suffering of all humankind and, to me, is an all-powerful God. And inscribed on the back, in letters so big that we can't ignore them, is Job's lament turned into a promise: if we are cut down, we will grow again into something new, we cannot be stopped. Maybe that’s another useful message to take into 2025. At the very least, we should consider it; we did write it down very big, after all.

Frank Oz.

Had the city’s bid to host the 2016 Olympics been successful, we would have added a fifth star to the iconic four-star Chicago flag. The first four stars represent other significant events from Chicago history and I know them but I'm not going to name them because I'm too humble to show off.

Hortus in Urbe, “The Garden in the City”, which is a deliberate mirror of the city's official motto, Urbs in Horto.

Probably just whatever the standard stuff is, why do you ask?

Apart from the fact that, though I do think he is a great songwriter and the messages in his lyrics are very relevant, Gerard Way is an objectively funny name to put there.