Since the death of former Eagle Scout David Lynch in January, I have now watched six of his ten films. They are, of course, great; I am still regularly thinking about different scenes in The Straight Story and Blue Velvet and Eraserhead and Mulholland Drive and how much I enjoyed all of those movies and how nice it is to appreciate good, human, moving, hopeful art in dark times. And then I watched 1984's Dune last weekend, which made me think about some very different things.

If you've read any of the remembrances of Lynch from earlier this year, you already know how Dune fits into the story: Lynch was a hot hand in Hollywood after two respected films and an Oscar nomination, and he got the chance to do a huge sci-fi epic, and it was a commercial, creative, and critical disaster, and because it was a disaster he got knocked off of the “studio franchise” path, and it was probably the best possible thing that could have happened to him artistically, because it gave him the freedom to make weirder stuff that had more vision and integrity and originality. If Dune had been a hit, Lynch could have been doing space operas for the rest of his career and we wouldn't have gotten Blue Velvet or Twin Peaks or Mulholland Drive.

But 1984’s Dune was never going to be a hit, because in Dune we have a fascinating artistic question: what happens when you give a director who is already extremely gifted a blatantly impossible job? The job was “make a Dune movie that's two hours long”, which is impossible. Frank Herbert's first attempt to adapt his novel for the screen was long enough for over three hours of screen time; Lynch's seventh draft (seventh!) of his screenplay was also about three hours and the studio made him cut everything to ribbons. The more current Dune film, directed by a different talented guy with significantly more resources, was over five hours long across two films and it still cut a ton of stuff from the book.

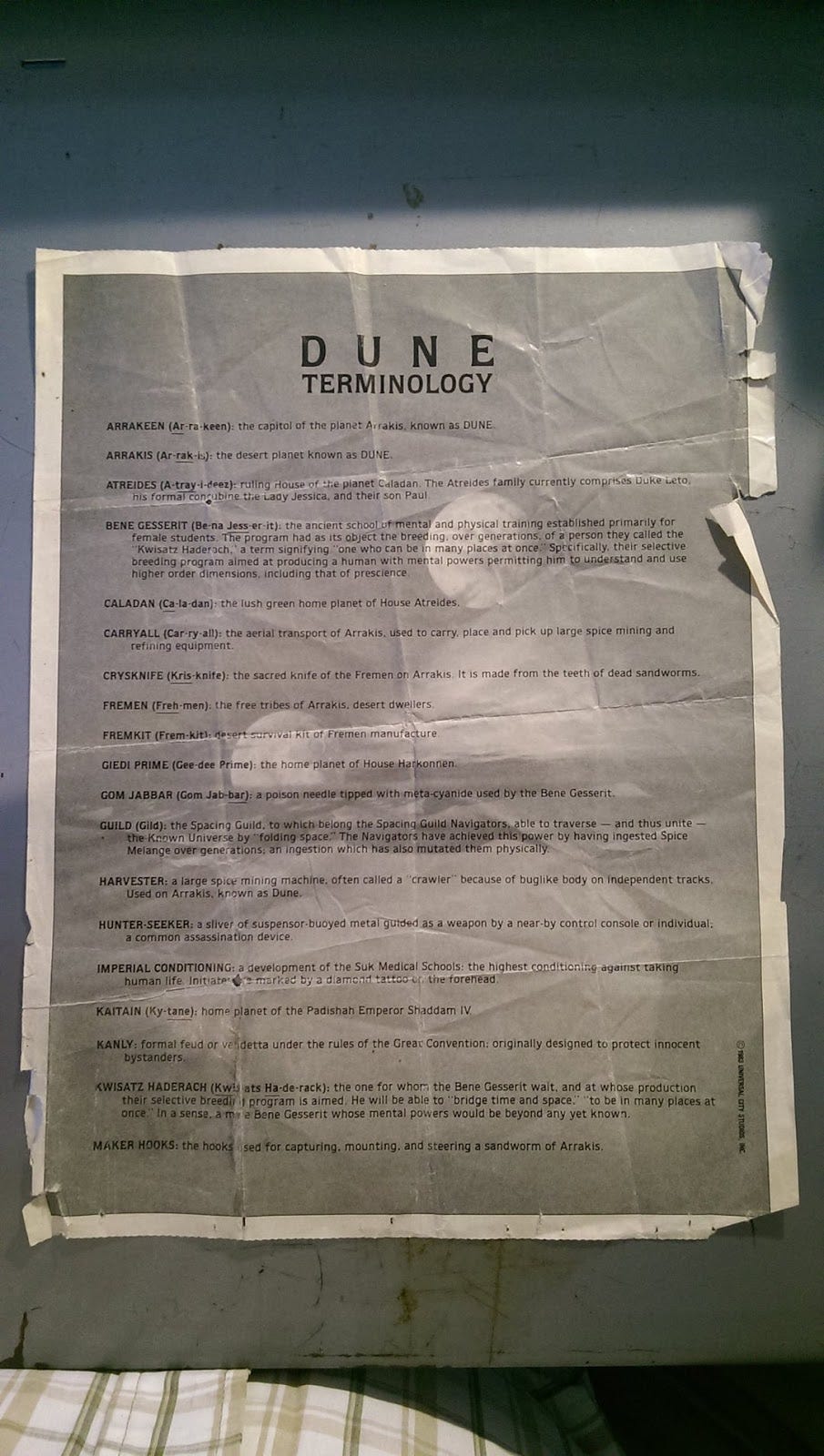

Absolutely nobody could have pulled this off, not even David Lynch. Lynch had already been nominated for an Oscar. He had already made a fully formed artistic statement with Eraserhead, which could have been “a dorky AFI student fumbles through creepy shit he thinks look cool”, but was instead tight and horrifying and moving and human and hilarious. Lynch knew how to make movies, even this early in his career. But the final 137-minute theatrical version of Lynch's Dune, the completed attempt by the immensely gifted man doing the obviously impossible job, is not “good”, in the sense that we expect a “good” sci-fi blockbuster to “make sense” and “have a coherent story”. The plot of the film is unbelievably rushed to the point of being illegible; if you haven't read the original novel at least twice, you will not understand anything that happens in the film. Two-thirds of the dialogue is just voice-over internal monologues that Lynch had to shoehorn in after the shoot to explain what the hell was going on on Arrakis; much of that, in turn, is narration from Princess Irulan, whose pretty important role in the novel is essentially cut entirely. Roger Ebert called it “one of the most confusing screenplays of all time” and he was correct. Movie theaters handed out glossaries to attempt to help the audience out during screenings.

And yet - there’s stuff in this movie that works, and works really well; the casting and acting and visuals are so bonkers and over-the-top that the film is extremely compelling just in its weirdness. Sting is one of the bad guys! Patrick Stewart has like a bald-mullet thing going on! There’s a gross yonic-mouthed brain-alien floating in a tank delivering ultimatums in the opening scene, and buddy that’s not in the book! I think the Lynch’s sandworms at night look better than the new sandworms in Villenueve’s film! Remarkably - as with The Straight Story - although the genre of this film is extremely against type for Lynch, this is a Lynch film without question. Stuff like the Gom Jabbar scene is extremely “directed by David Lynch”, and for my money the 1984 version is better than the Gom Jabbar scene in the 2021 film. And I like the 2021/4 film plenty, but where it is sometimes the kind of aseptic that you have to be to get studio money in the 2020s, Dune is audaciously weird and surreal for what was supposed to be a mainstream blockbuster, and nobody can deny that Lynch had glimmers of awe-inspiring genius here while trying to do the impossible job. Look at Kye MacLachlan, in his first film role, weirding out here, and tell me this doesn’t seem like weird shit you have to at least check out:

A thoroughly gifted man got the impossible job: what an incredible thing to witness, what beauty even in its failures, what brilliance in the moments when it was successful. Even though Dune failed in many ways, the failure still accomplished a great deal, led to even greater things, and was still, at the very least, extremely interesting.

I guess the easy comparison here is to say that being Pope is an impossible job, as the College of Cardinal convenes and prepares to, in theological terms, “conk open a clave one with the boys”. I could say that Pope Francis was an immensely gifted man who was given an impossible job of leading the Catholic church in this era, and who still accomplished a great deal and who set us up for even greater things and whose papacy was extremely interesting. There’s truth to all of that, but it certainly wouldn’t be the whole picture. Some of the things I would consider Pope Francis’ failures - I’m thinking in particular of some of his responses to the ongoing sexual abuse crisis - are less “he was given an impossible job” and more “we’ve been dealing with this for decades and every single prelate still refuses to learn from it”. Whatever, you see how the comparison kind of works for the previous Pope and how it will kind of work for the next Pope. But the actual immensely gifted people being given the really impossible job, of course, are all of us.

Here’s the impossible job, talented though we all are: we have to actually do the things the Gospel told us to do, in a world that does not seem to want that at all. We have to find the suffering and then help them, we have to feed the hungry and clothe the naked and care for the sick at our personal expense. The source material is not set up to translate at all within the confines of the world today, which appear designed to just increase everyone’s suffering forever. We can, if we like, do this job in the name of the Catholic church, an institution that has been bad at almost everything for just about two thousand years. But the people that I admire the most just do the impossible job any way they can and find those glimmers of awe-inspiring genius when they can.

Check out this great piece from the Catholic Worker’s online newsletter which ran a few days ago. To be fair, this isn’t the official newsletter of the Catholic Worker movement, because there isn’t really an official Anything of the Catholic Worker movement, as the piece explains. The Vatican or the archdiocese doesn’t set up Catholic Worker houses. There’s no national director and no (reliable) national directory. There are just people, some who need help and some who have a little more to give, and they’re just doing what they can. Jerry Windley–Daoust lays this all out in a tongue-in-cheek transcript of an imagined conversation, a writing device which I personally try to avoid and have not used at least a dozen times throughout the course of writing G.O.T.H.S. including in my essay that I published yesterday. At the risk of repeating stuff I’ve said a bunch of times before, this is how the immensely gifted person does the impossible job: they just shut up and do it and don’t concern themselves with things like being successful:

“...anyone can start a Catholic Worker community without getting the approval or say-so of anyone else in the movement. There’s no paperwork, no corporate training, no ordination. One day, you’re just sitting around talking; the next, you’re having arguments with community members about the best way to organize the refrigerator to accommodate the twelve gallons of leftover pasta salad some church just donated from a funeral lunch…when you tell others about the Catholic Worker movement, be sure to tell them that we don’t count franchise numbers, or the number of clients served, or the number of card-carrying members. We’re not primarily worried about ‘success’ because we know, at the end of the day, we’re not going to remake the world on our own. That’s God’s job. We’re just called to cooperate, to do our part. And if we do that, then maybe at the end of the day we might look back and see that we helped make something beautiful, something bigger and more wonderful than we could have ever imagined on our own. Maybe we’ll see that, together with other people of good will, we did something to help make the world a place in which it is easier to be good, as Peter would have said.”

I admire Catholic Workers, and those who do similar work, because of their direct material service to the poor, but also because they just do it, without waiting for an institution to sign off on things or for circumstances to improve. Along the way, people are fed and clothed and sheltered and protected, sometimes not as well as we may hope, but God is still seen and heard every day in this work regardless, which can be done in all seasons and in all circumstances.

Again, at the risk of repeating myself, we all have work to do. We are immensely gifted people - since we are all children of God - who have all been saddled with an impossible job. What an incredible thing to witness, what beauty even in our failures, what brilliance in our moments when we are successful at caring for the least among us. May our work accomplish a great deal, lead to even greater things, and, you know, be interesting and even weird at times.