The Essay that Pretends to be About Passion of the Christ in the Intro but is Really About Hellboy

Celebrating 20 years of one of the most important Catholic films of all time

“People say, you know, "I like your Spanish movies more than I like your English-language movies because they are not as personal," and I go "Fuck, you're wrong!" Hellboy is as personal to me as Pan's Labyrinth. They're tonally different, and yes, of course you can like one more than the other—the other one may seem banal or whatever it is that you don't like. But it really is part of the same movie. You make one movie. Hitchcock did one movie, all his life.”

-Guillermo del Toro in 2013

Look, we’ve got a big anniversary coming up when it comes to Catholicism and pop culture, and it’s not one that I can avoid writing about. We’re coming up on twenty years since the release of a big, important, Catholic movie by a big, important, Catholic director. The movie and the director - and you know exactly what and who I’m talking about - are polarizing, to be sure, but it would be silly to ignore the impact that the director and the movie have had on the cultural understanding of Catholicism in the 2000s, and the impact that they had on my understanding of Catholicism during a formative period of my life.

And let's be real: we're talking about an extremely well-made and well-acted movie, helmed by an Oscar-winning Best Director. It took big risks that were unheard of in this era of filmmaking, and I would argue that those risks paid off, narratively and aesthetically. Whatever your personal distaste for how this story may have been adapted and handled, there's no question that it is technically impeccable, and that impeccability is all in service of the very powerful message of the film. The director - whose understanding, lifelong experience, and practice of Catholicism is, obviously, very different from mine - wanted to make a movie to show audiences, albeit viscerally at times, how much we are truly loved by God. It was an admirable goal, executed very well but not perfectly, and it is worth observing the twentieth anniversary of the film this year, to examine its ongoing relationship to faith and culture.

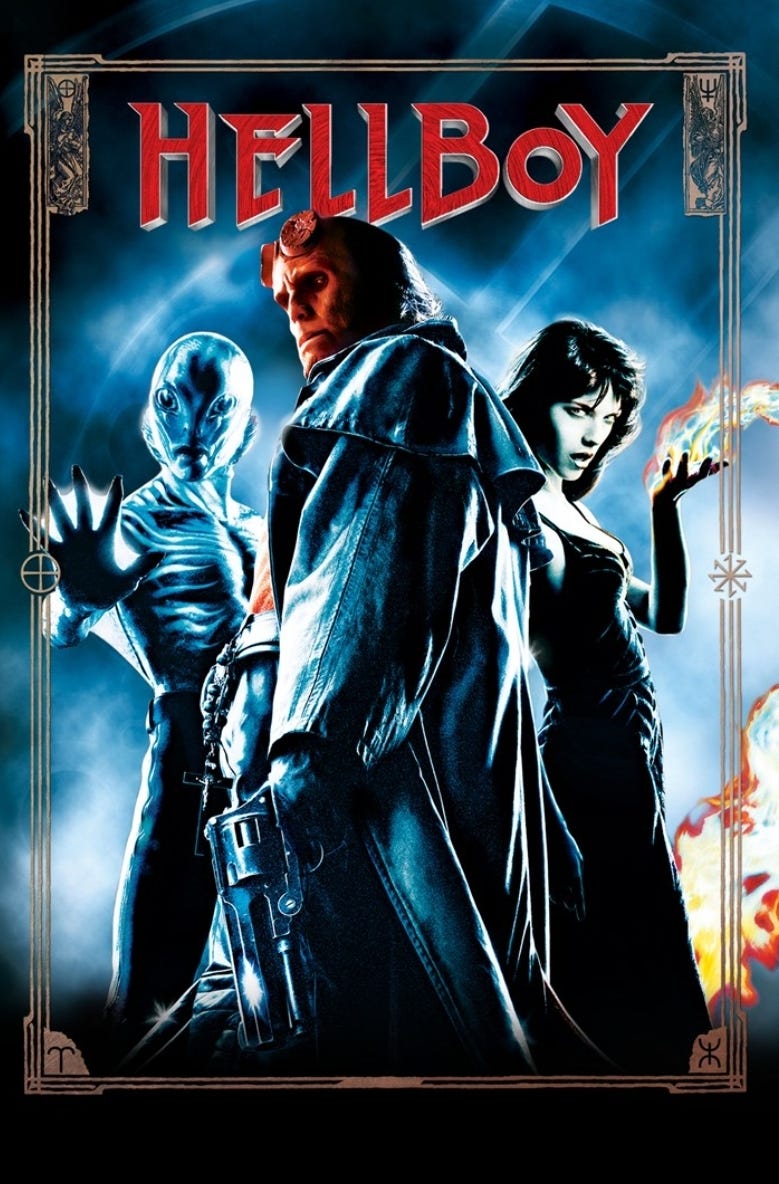

So, with that, it's time for G.O.T.H.S. to finally take a look at Guillermo del Toro and his early 2004 adaptation of the Dark Horse Comics series Hellboy. That's what we were talking about, right?

“Wow Tony you spent 300 words on a stupid bait-and-switch, which you even spoiled in the title of the essay, and now you're committing to rewatching Hellboy and writing about it?” Yes, it's currently on Netflix and I'm delighted to do it. It's hard to imagine any other film, with a ton of Catholic imagery, with an explicitly Catholic message, by an Oscar-winning Catholic director, released in the first half of 2004, that is better than Hellboy, and if you suggest any other options, I'll just repeatedly yell “NO IT'S HELLBOY” at you until you stop talking.

I'm kind of kidding, but not really: while Hellboy is by no means a profound life-changing cinematic experience, it's a pretty entertaining comic book film that basically came out five to ten years too early. This was 2004. The first Christopher Nolan Batman film was still a year away. Iron Man and the Marvel Cinematic Universe were four years away; Marvel wasn't a Disney subsidiary yet, and they weren't even really a movie studio yet, choosing instead to license out properties like Spider-Man and the X-Men. But the action and the quips are all there, and if this film had come out in 2014 we would have all been like “ugh another one of these”, but in 2004, it was actually innovative, and it works mainly because the casting is so spot-on: del Toro wrote the script with Ron Perlman in mind for Hellboy, and refused to sell it to a studio that didn't want Ron Perlman in that role, and he was right, because Perlman is perfect. The wonderful John Hurt plays Hellboy's adoptive father, the professor who runs the FBI's Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense. Frequent del Toro collaborator Doug Jones also goes into heavy makeup to play Abe Sapien, Hellboy's aquatic teammate1. Selma Blair is in it and she shoots fire out of her hands, which is kind of hot I guess.

The premise of Hellboy is this: in the final days of World War II, desperate Nazis attempted to open a portal to Hell to coax an eldritch horror from the blind eternities in order to tilt the war back in their favor. Allied soldiers close the portal quickly, but not before a baby demon escapes into our world. John Hurt takes in the demon and raises it as his son, and after the war ends, they return to the States and form the FBI's aforementioned bureau for fighting demons and monsters, and fifty years later there are a few non-dead Nazis trying to re-open that portal, and a now-adult cigar-chomping gun-slinging wise-cracking Hellboy has to stop them by kicking some ass. It’s not an especially complicated film.

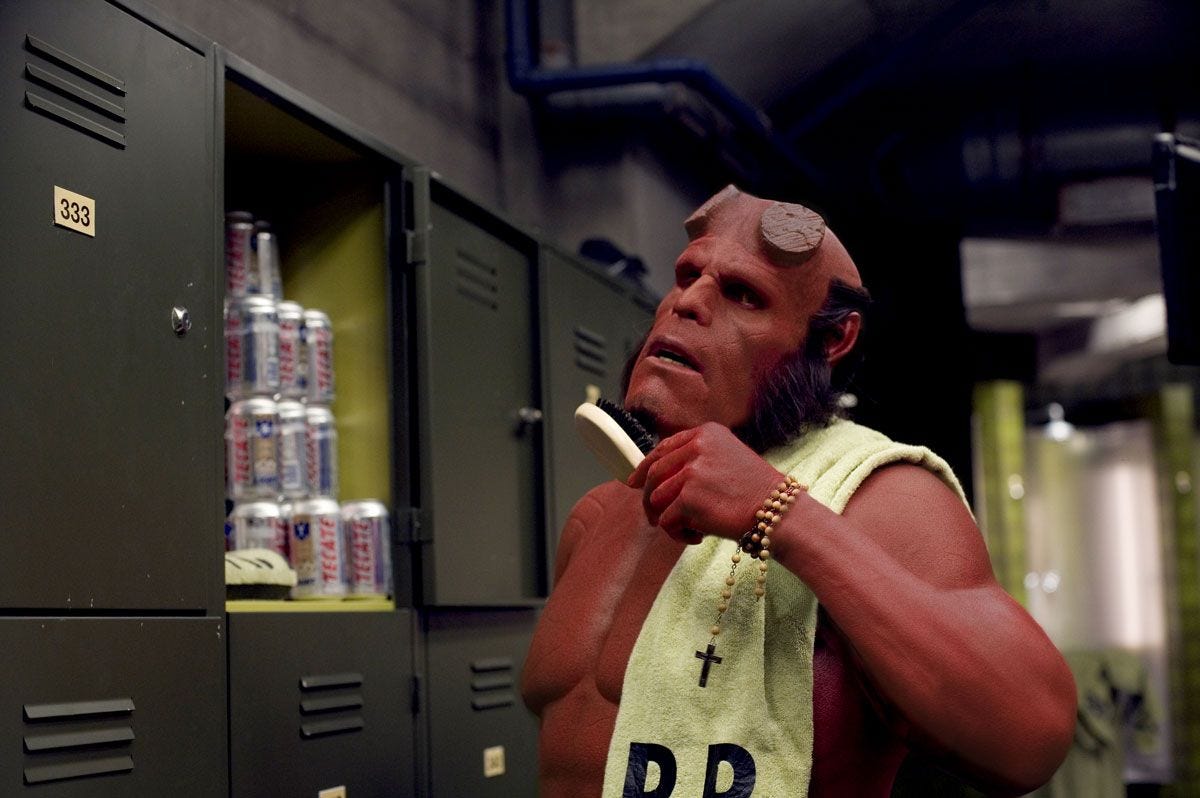

But this is a very, very Catholic film. Hellboy - and John Hurt's character who raises him - is a practicing Catholic who carries a rosary with him at all times. His gun is named The Samaritan, clearly presaging Pope Francis’ focus on that parable in the encyclical Fratelli Tutti. The seal of the Bureau for Paranormal Research and Defense is a close-up of Saint Michael's fist holding a sword, and there's a life-size statue of Saint Michael slaying a demon in the office of the Bureau. In the climactic scene of the film, Hellboy has given into despair and embraced his demonic nature, and is about to reopen the Nazi Hell Portal, when his FBI handler screams “REMEMBER WHO YOU ARE!” and literally throws Hellboy the rosary he dropped in the previous scene, which convinces Hellboy to become good again.

THE CLIMACTIC SCENE OF THE FILM IS THAT A GUY IS ABOUT TO OPEN A PORTAL TO HELL AND THEN HE PICKS UP A ROSARY AND DECIDES NOT TO OPEN THE PORTAL TO HELL ANYMORE. I DON'T KNOW HOW MUCH MORE CATHOLIC YOU CAN POSSIBLY MAKE A SUPERHERO MOVIE.

More than that, though, Hellboy is constantly wrestling with the fact that he was created to do evil and was never meant to fit in to human society. And throughout the film, which I'm not going to pretend is subtle, we hear all sorts of lines about what it means to love and accept someone, or love and accept yourself knowing that they, or you, are imperfect, just like everyone else. At one point, Hellboy's FBI handler recalls hearing from his parents that “We like people for their qualities, but love them for their defects.” When John Hurt is captured by Nazis who mockingly ask him if he knows Hellboy's true (demon) name, Hurt defiantly responds “I know what to call him. I call him Son.”

Loving the seemingly unlovable and monstrous, loving without any expectation of change, loving as God loves us, is a theme that appears all over del Toro's work, from the Best Picture-winning The Shape of Water to the beautifully animated but tonally bizarre stop-motion adaptation of Pinocchio2. Sometimes we love a puppet who doesn’t understand the world, sometimes we love a demon who doesn't trust himself to do the right thing, sometimes we have sex with a fish-man; life is a beautiful rainbow. And del Toro is not a practicing Catholic anymore, but his exploring this theme across multiple films is absolutely, according to him, a result of his Catholic upbringing. From his 2016 book:

“A lot of Mexican Catholic dogma, the way it's taught, it's about existing in a state of grace, which I found impossible to reconcile with the much darker view of the world and myself, even as a child.I couldn't make sense of impulses like rage or envy and, when I was older, more complex ones, you know. I felt there was a deep cleansing allowing for imperfection through the figure of a monster. Monsters are the patron saints of imperfection.”

And from an NPR interview he did while on the press circuit for The Shape of Water:

“The movie is about connecting with 'the other’. You know, the idea of empathy, the idea of how we do need each other to survive. And that's why the original title of the screenplay when I wrote it was A Fairy Tale for Troubled Times, because I think that this is a movie that is incredibly pertinent and almost like an antidote to a lot of the cynicism and disconnect that we experience day to day. A very Catholic notion is the humble force, or the force of humility, that gets revealed as a god-like figure toward the end.”

Hellboy is a monster, but there's a man out there who loves him and calls him Son, without needing him to change. Hellboy is told by his father that we need to value each other to survive, even if we seem unlovable or monstrous, and it takes the whole movie, and a rosary, for that lesson to sink in. If you are ‘the other’, know that you are worth loving, Hellboy. Compared to the divine, we're monsters, too, we are patron saints of imperfection, and God calls us all sons and daughters anyways, almost defiantly against the forces of darkness. What a beautiful lesson about Catholicism to share with moviegoers, and it's impossible for me to imagine any other film from this era being more Catholic because, to be honest, I've never actually seen Passion of the Christ.

As Real Hellboy Heads know, all of Jones’ lines were dubbed over by David Hyde Pierce since Pierce was assumed to be a bigger box office draw, but when Pierce saw how good an actor Jones was, he was so embarrassed at doing the dub that he refused to take a credit for Hellboy or promote it at all so that all of the credit could go to Jones. Jones did his own dialogue in Hellboy's 2008 sequel.

Although being tonally bizarre is extremely true to Collodi’s original Pinocchio story.