This essay is about a nun, I promise.

CHAPTER ONE - STEVE

Steve Albini died last month. While Albini was a guitarist and frontman for multiple rock and punk bands, he was best known as a prolific and universally beloved record producer (although he hated being called a producer and preferred terms like “engineer”). Every obituary of Albini mentioned the totems of grungy punky rock that he midwifed into the 90s, including Nirvana's In Utero, Pixies’ Surfer Rosa, and PJ Harvey's Rid of Me. Multiple punk albums that I love and have listened to on repeat for years, from classics like Superchunk's Foolish to more recent works like Cloud Nothings’ Attack on Memory, are Albini's work, usually recorded at the Chicago studio he owned: Electrical Audio, near Belmont and Elston. The legacy of Albini's albums alone make his death a huge loss for American music.

But Albini also represents something else in American music, something every music writer has recognized in their eulogies. Albini had tremendous professional integrity and generosity; he held, throughout his life, a view that the work of making music was not a career with an end goal of financial stability, but something good as an end in itself. He did it for love, and the love was obvious in who he chose to work with, and where he chose to work, and, perhaps most importantly, how he chose to get paid.

Albini was unusual among record producers - at least at his level of prestige - in that he never took royalties or residuals for his work. Again, this is the guy that Nirvana chose to hire after they had become the biggest band in the world: Albini could have made a nickel off of every sale of In Utero for the rest of his life. But he didn't. Instead, he wrote a very famous letter to the band when they first started working together, outlining his approach to record production and, more importantly, his approach to compensation:

“I explained this to Kurt but I thought I'd better reiterate it here. I do not want and will not take a royalty on any record I record. No points. Period. I think paying a royalty to a producer or engineer is ethically indefensible. The band write the songs. The band play the music. It's the band's fans who buy the records. The band is responsible for whether it's a great record or a horrible record. Royalties belong to the band. I would like to be paid like a plumber: I do the job and you pay me what it's worth. The record company will expect me to ask for a point or a point and a half. If we assume three million sales, that works out to 400,000 dollars or so. There's no fucking way I would ever take that much money. I wouldn't be able to sleep…Some people in my position would expect an increase in business after being associated with your band. I, however, already have more work than I can handle, and frankly, the kind of people such superficialities will attract are not people I want to work with. Please don't consider that an issue.”

In an industry where everyone is exploiting everyone else, Steve Albini actually cared about things like ethics and not taking money that wasn’t his, even if it cost him hundreds of thousands of dollars. If you were starting a punk band and saying to yourself “I'm never gonna sell out,” you dreamed of working with Steve Albini, because he never did abandon his principles, he did it the right way, and all he had to show for it was a career doing what he loved, an outpouring of respect after his death, and a catalog of unimpeachable rock albums. He showed artists everywhere that sticking to your principles could actually be worth it, if you were willing to work like a plumber. Trevor Shelley de Brauw, writing for Welcome to Hell World, noted that “the words I see coming up again and again in the many remembrances circulating about Steve are not “strategic” or “ambitious,” they are “generous” and “principled””; the title of his eulogy for Albini was “How to Live an Intentional and Ethical Life”. Electrical Audio's statement on Albini's death noted that:

“He saw recording almost as an ethical imperative to document the music of the world around him. Steve had a profoundly generous spirit; he was always willing to share his knowledge and expertise, and his time and attention. He gave all of us at the studio a shot in an ever-dwindling industry and became our fierce advocate, as he did for countless others in his orbit over the years.”

Albini could have been a Jack Antonoff-like titan in rock music, working with stadium acts in Los Angeles; instead, he worked with indie bands out of a two-room studio in Chicago that you can just book right now if you have a band, and he clocked in every day so he could bring out the best in the musicians that worked with him. At the time of his death, if you wanted to hire Albini to record your band, his rate was $900 a day, and again, that was all it cost, in 2024, to hire the guy who fucking produced In Utero, a guy who could have easily charged five times as much. As he made explicit by comparing his pay scale to that of a plumber, Albini saw himself as a lifelong journeyman. Driving the point home even further: Electrical Audio uses an electrician jumpsuit as their unofficial “uniform” and you can buy one on their website:

Albini was great at what he did, and he wanted to make sure he had no excuse to stop doing it. He had to keep working. His life's calling was not to have one big hit and coast on that, it was to keep doing the work. This was a man who couldn't make four hundred grand on one job because he wouldn't be able to sleep at night; he wanted to wake up the next morning and go back to work, the work which was good in itself because he loved doing it. There's so much more here I could say - he was a Chicago Guy, he also was good at writing songs, he had a great deadpan sense of humor - but now I want to move to the bands.

Many of the artists who made music with Albini not only loved his integrity, they practiced it themselves, operating counter to the heartless music industry and seamlessly integrating their work, their passion, and their lives. I want to highlight two of those artists here, because they happen to be two that I love, and they are both very “against type” for a producer best known for making punk and grunge records. For example, he worked with one band out of Duluth that is famous, first and foremost, for playing very, very slow.

CHAPTER TWO - ALAN AND MIMI

“No, you're never gonna feel complete

No, you're never gonna be released

Maybe never even see, believe

That's why we're living in days like these”

Low - anchored by Mimi Parker and Alan Sparhawk, above - is slow. They were pioneers of a 90s “slowcore” genre that took the elements of grungy 90s rock and iced them down to find something new and beautiful at a much slower speed. Low would play shows in punk and metal clubs that were used to mosh pits, and fans would come and all sit on the floor for their concert. A good place to start in their varied catalog would be the 2001 album Things We Lost in the Fire, produced by Steve Albini.

You'll notice one other thing right away about this song, besides the tempo: the harmonies. Sparhawk and Parker make these beautiful two-part vocal harmonies in all of their songs. They've been playing together for decades, and they're obviously talented from a straight musicianship standpoint, but I think there’s another reason the two of them sound so good when they sing together: they love each other and have known each other their entire lives. They first met in grade school and eventually got married and formed a band that put out 13 albums, one of which was engineered by Steve Albini and got an 8.7 from Pitchfork. As that publication wrote in a separate 2023 piece:

“Low’s music became a go-to resource for those looking to better understand their own sadness or seek comfort from the harsh realities of an unrelenting world…The two met as kids in grade school and, as teenagers, began their lifelong relationship together. They developed their own shared language in tandem with learning how to navigate the world, graduating from holding pencils to instruments to children.”

I've been married for nine years and a parent for five, during which the world has gotten a lot weirder and scarier. To wake up every day and be an awake and alive person is a tremendous amount of work, but doing it with a partner, or a team is…surprise! Still a tremendous amount of work! Growing and changing with other people in a decaying world is hard. Sparhawk and Parker thought it was hard, too, and they carried each other, they wrapped each other in their voices, and helped each other get through each day. The work of making music helped sustain their family. Sparhawk spoke to the importance of this daily work in a 2021 interview:

“Sparhawk…has kept himself busy with extracurriculars. He’s in a Neil Young cover band; he started a funk side project with his teenage son; and he teaches guitar at the local high school. Distilling the kind of advice he gives to his students, he says, “Whatever you want to be, just make that a part of your everyday. If you want to be a writer, write every day. If you want to play guitar, put it right next to you where you’ll see it every day. Do it every day, and it will become part of you.””

Again, the frontman for a beloved band who once got to work with Steve Albini still teaches guitar, and still wants to make music “part of his everyday”. And he made his marriage and his faith part of his everyday, too: see, Sparhawk and Parker were practicing members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. But that presented its own set of challenges, as, to their horror, they saw their fellow LDS members throw in their lot with ascendant American white nationalism, and wrestled with their place in their own church. These anxieties came out in Low's final two albums, 2017's Double Negative and 2021's HEY WHAT, where the two experimented with digital deterioration, but kept their harmonies floating on top of all of the decay. Sparhawk gave out some marriage advice in that 2021 interview:

“Try to end every day together. Don’t let it go overnight. This advice was given to us when we were first married: Always pray together at the end of the day. I’m not saying everybody has to pray—even though I would encourage everyone to pray. It was more just to have some surrender. There’s a giving up of selfishness. If you had a grudge or something bothering you during the day, you either have to swallow it at that moment or talk about it and figure it out so that you can be genuinely together.”

In Low's words, and Low's work, and Low's marriage, and in the ethos of Low's most famous producer, we see the same commitment to working every day, through challenges in marriage, through existential dread, through evolution of your band's sound, through crises of faith. The work is a good in itself, not a path to someday coast.

Mimi Parker died of ovarian cancer in 2022. Sparhawk is without his lifelong partner, although he plans to release a solo album in 2024. He's not going to stop making music. He still has to make it part of his everyday. Arguably, it's even more important that he does that now.

Low's music was a little against type for Albini, but at least they still used, like, guitars and drums and stuff. Albini also once flew out to California to sit in a candlelit room and record a woman on a harp. Well, the woman on the harp.

CHAPTER THREE - JOANNA

“And it pains me to say, I was wrong

Love is not a symptom of time

Time is just a symptom of love

And all the nullifying, defeating, negating, repeating

Joy of life”

Joanna Fucking Newsom, recently introduced at a concert as “the high priestess of acoustic music”, the classically trained harpist who who is possibly America's most ambitious and greatest living songwriter, the actress who narrated Paul Thomas Anderson's Inherent Vice because she could sound like a human while reading Thomas Pynchon out loud1, but who also guest-starred in Brooklyn Nine-Nine because her husband is Andy Samberg, makes music that no other artist can. For an introduction to the absurd ambition and scale and emotional power of her music, you could try her 2006 album Ys, produced by Steve Albini. Albini recorded her solo on harp, and orchestrations were added afterwards, but also just listen to her when she just has her harp and is gliding over those Minimalist-influenced polyrhythms:

Each of the five tracks on Ys averages out to about twelve minutes, and features similarly knotty language and metaphors. It's probably not for everyone, and neither is Have One On Me, the massive triple album that followed it. But to me, they're incredible and affecting works of art. From Pitchfork’s original review of Ys:

“This isn't a great album because she owns a dog-eared encyclopedia, or because it stands above the cheap rewards or superficial freakiness we expected from her. It's great because Newsom confronts a mountain of conflicting feelings, and sifts through them for every nuance. It's intricate and crammed with information, but it's never bookish, and she never sits back in a spell and lets her heart flutter: She swoops into the sky and races across the ground, names every plant and every desire, and never feels less than real.”

It sounds weird to say this about twelve-minute intensely personal songs for harp, but: they work even better live than they do on the album. In 2019, Newsom started a solo tour, jumping between her harp and her piano and playing selections across all four of her albums. A reviewer described the show like this:

“A 360-degree entertainer, moving between the piano and harp, singing into a little bud mic with gusto, even when she professed serious exhaustion, she took on the feel of a vaudeville star, a ragtime pianist, Nina Simone, Little Richard, a natural member of a lineage of musicians that didn’t need anything other than a keyboard to bring music and all its possibilities to life. It was a classic and intimate form of entertainment. And it felt organic, rich, timeless, able to survive digital creep. It felt like the point of life, someone making something, some people enjoying it, happiness.”

Joanna performs music and makes “someone making something, some people enjoying it” feel like “the point of life”, just as Low did by growing together and letting their music grow around them, just as Albini did by seeing “recording almost as an ethical imperative to document the music of the world around him.” And I can cosign that review of Newsom’s concert, because I went to one of the shows on this tour, in Chicago in October 2019.

Let me just tell you how good she is as a songwriter and performer: at the show I attended, she performed “Time, as a Symptom”, the final track from her most recent album. That specific song, on the album, ends with Joanna repeating the words “white star, white ship, nightjar, transmit, transcend” over and over, eventually cutting off in the middle of “transcend”. Well, the first track on that same album is written in an adjacent key and starts with the line “Sending the first scouts over”, which means, if you play the final track and then immediately go back to the first track, you can move back to beginning of the album seamlessly, the lyrics and music form a perfect loop. Which is what she did at this concert - she played that final track and went directly into the first track - and then, as if that weren't impressive enough, during the bridge of the latter song, she stopped playing piano, spun around on her butt, grabbed her harp which she had strategically placed behind her, played the bridge perfectly, put the harp back down, spun around, and finished the song - which, again, was two songs - literally without missing a beat. She did all of this about 90 minutes into a two-hour concert where she performed multiple fifteen-minute multi-movement works, which ain't exactly four-chord rock songs, from memory. The writing and the staging and the performance, of these songs that have referenced, through dense metaphor and language, her breakups and her marriage and her motherhood, are all detailed and intricate and require tremendous labor and attention, because Newsom wants to show that labor to everyone, because it is, for her, an act of love, the point of life in itself2.

I will leave you with one last thing about Joanna Newsom: she normally performs while wearing these colorful and elaborate gowns - you can see in the video above that she even coordinated her dress and her wireless mic pack - but after Albini's death, in tribute to her late friend who also believed that the point of life was someone making something and somebody else enjoying it, she switched to the Electrical Audio jumpsuit:

I would like to talk about the nun now.

CHAPTER FOUR - CORITA

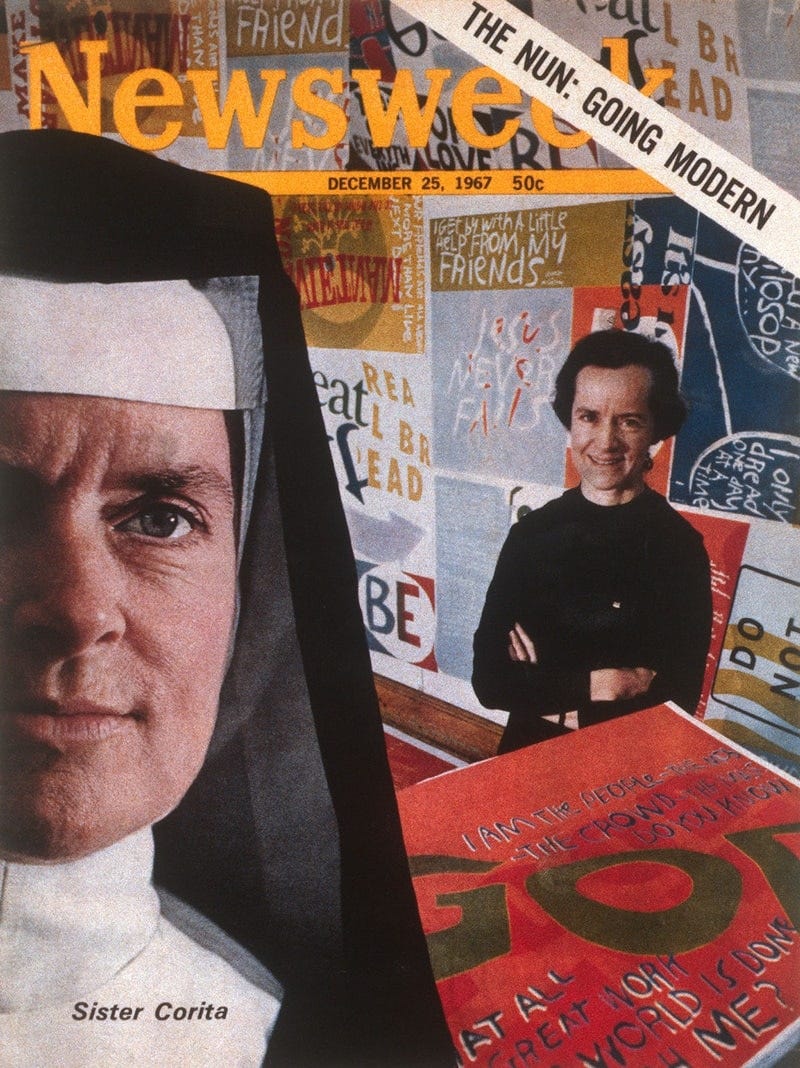

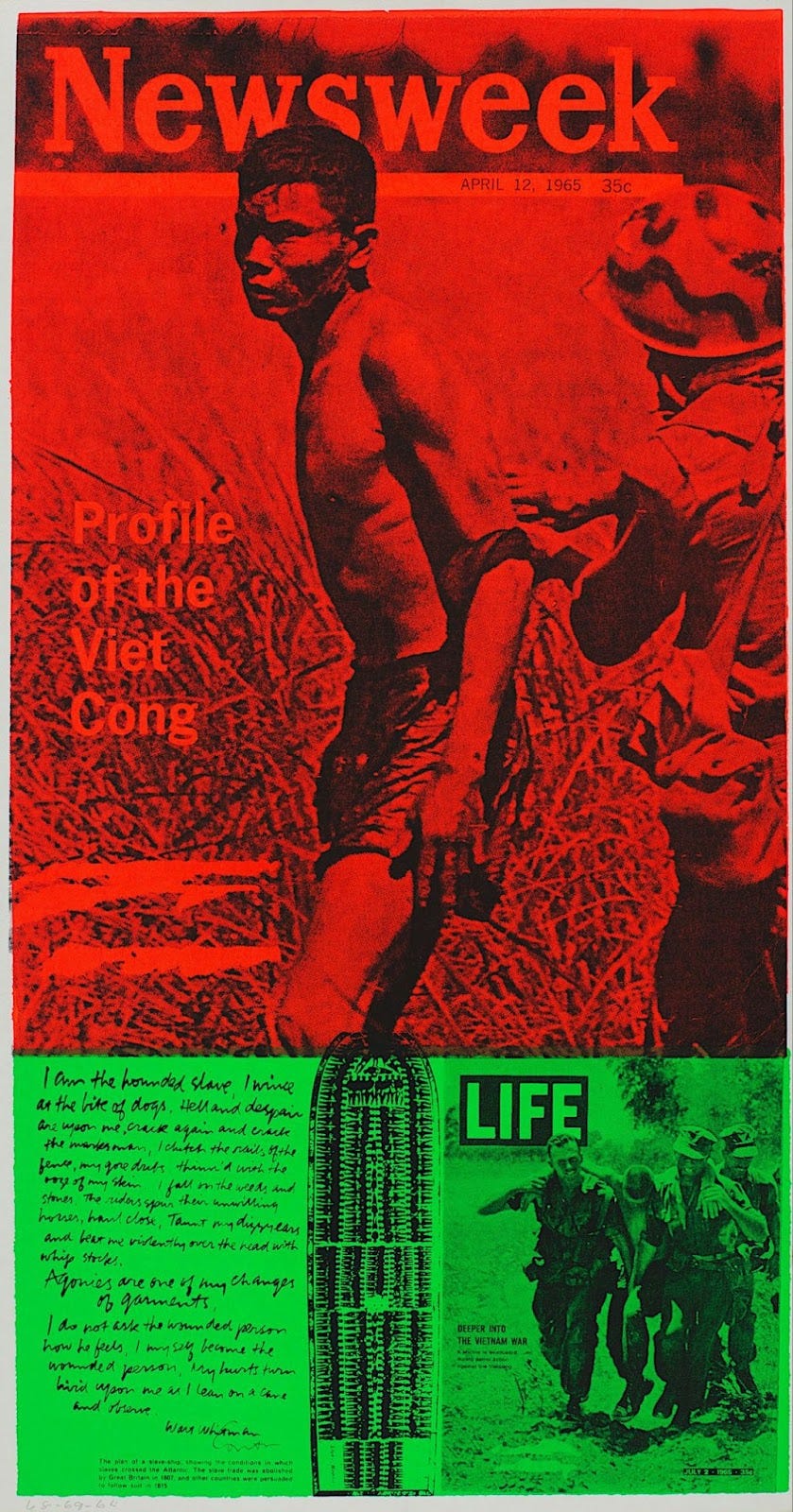

Do you know who Corita Kent is? I had no idea who this person was. Her artwork is in the collections at LACMA, MOMA, and the Met; it's even being featured in the current Venice Biennale as we speak. She was even on the cover of Newsweek in 1967:

And I had never heard of her until my daughter found this picture book at our local public library and made me read it to her:

So now Corita Kent is one of my favorite people. She joined the sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary at age 18 and earned two art degrees. Her day job, for over twenty years, was teaching art at the now-defunct Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, and those classes became an important incubator for twentieth-century West coast experimental artists, due in large part to Corita’s freewheeling teaching style. These were her rules for the IHC art department, posted on the wall in her classrooms:

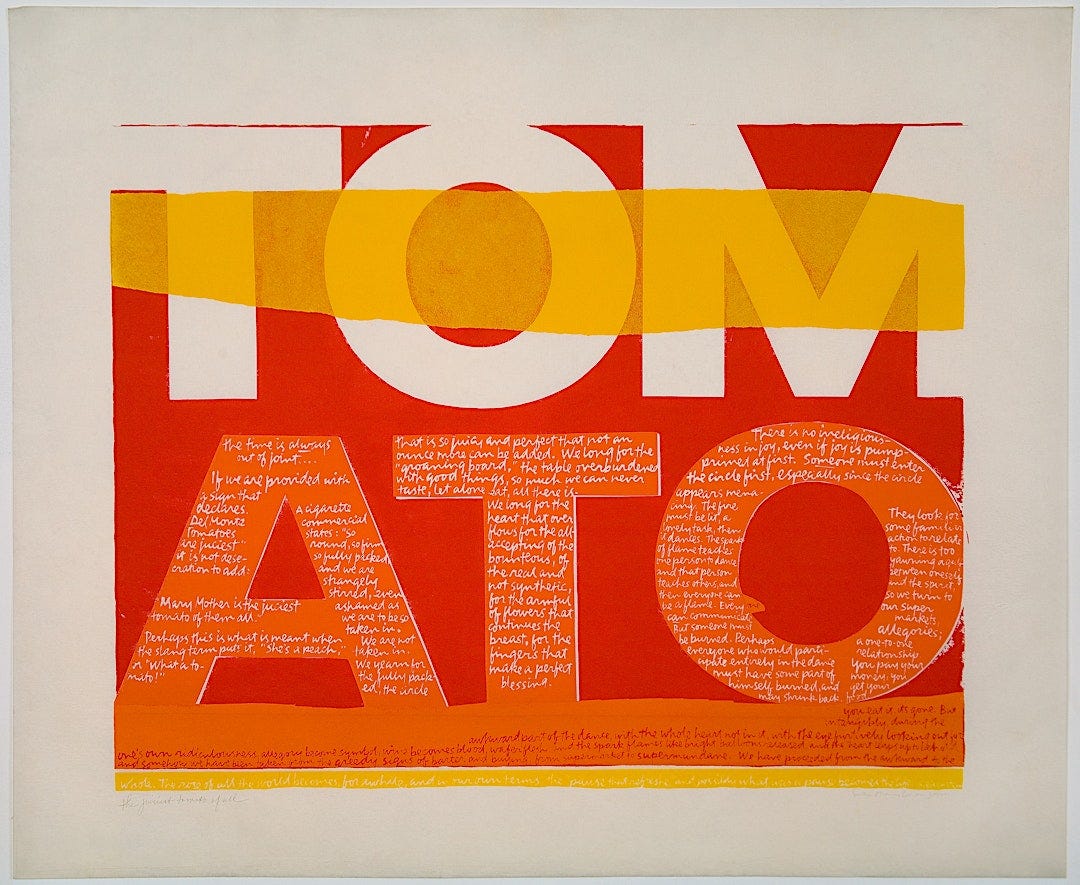

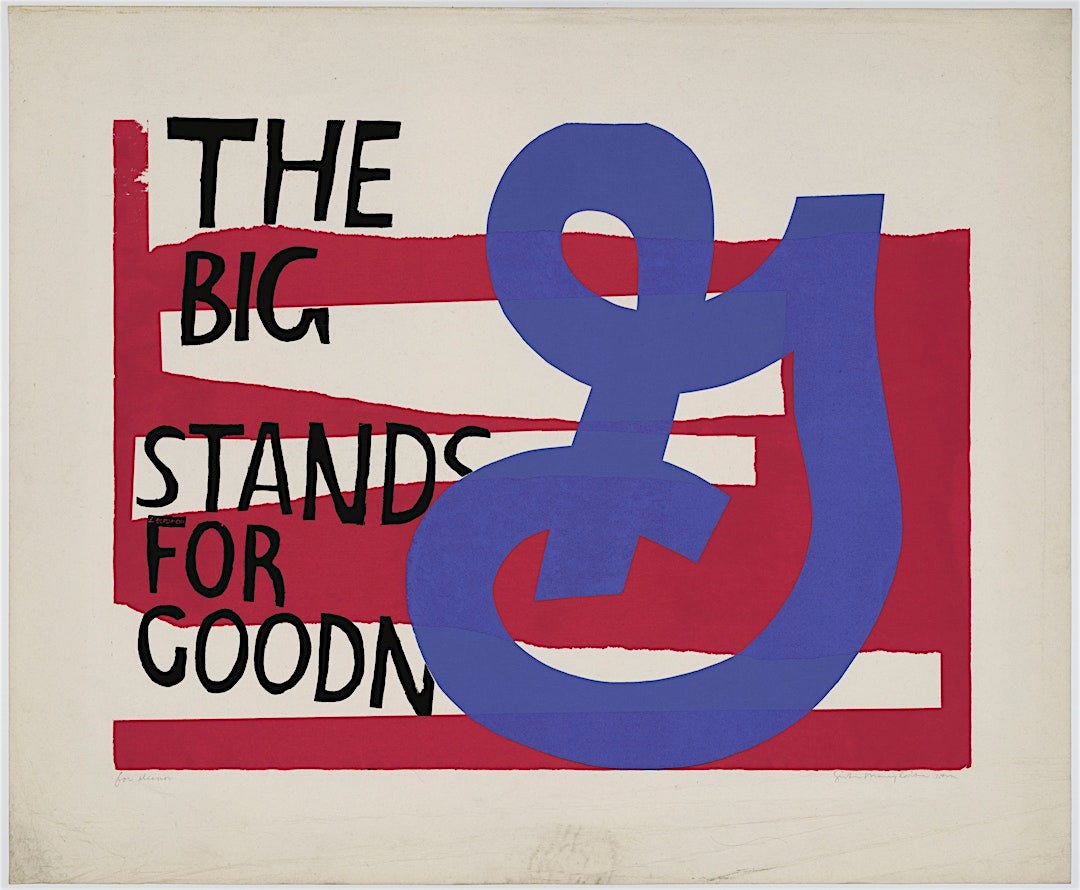

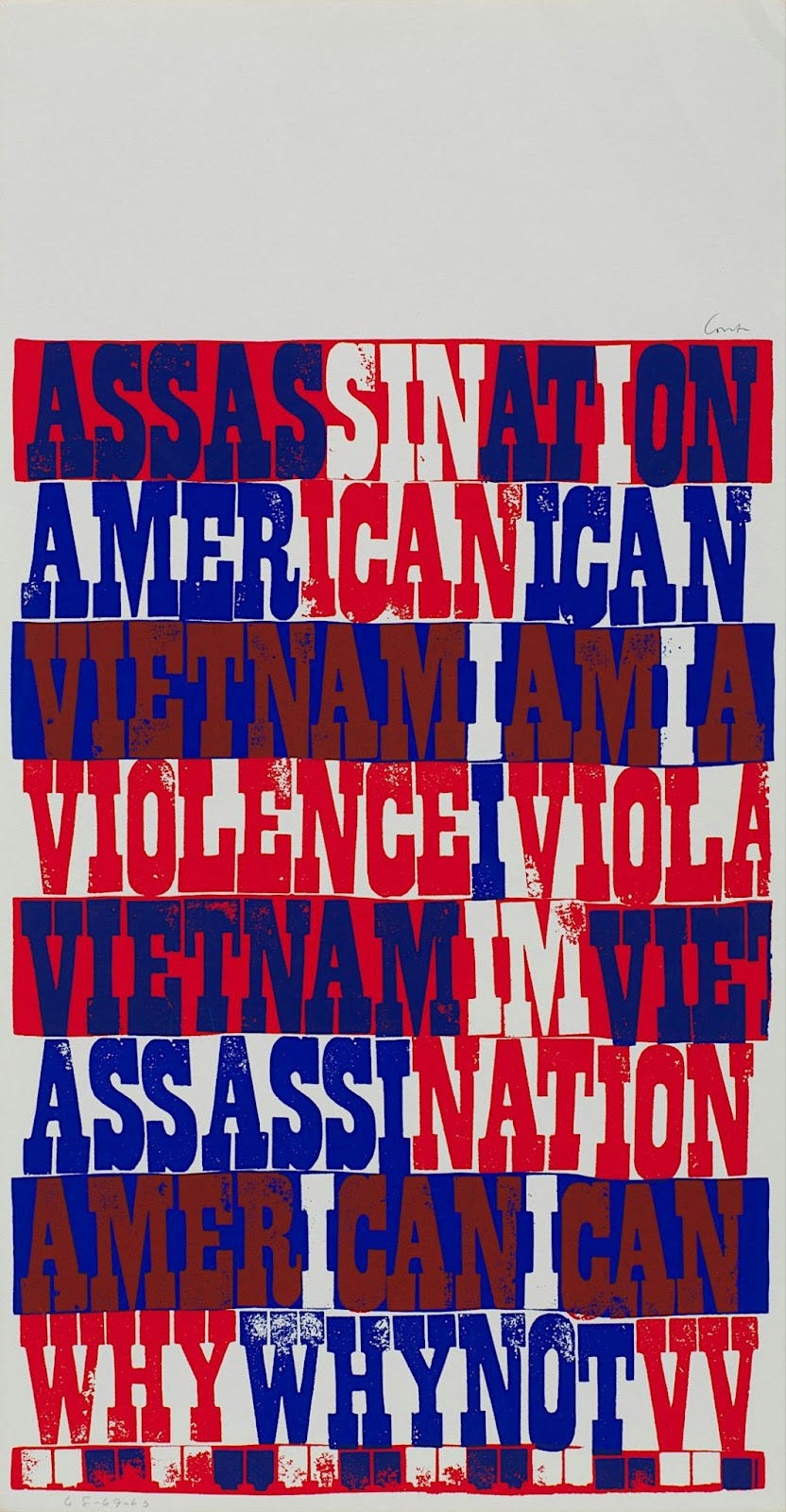

Besides the obvious dry humor of “there should be new rules next week”, I want to highlight rule number 7: “The only rule is work. If you work it will lead to something. It’s the people who do all of the work all of the time who eventually catch on to things.” And Corita did quite a bit of work herself; she was a prolific and innovative screenprinter, obviously influenced by Andy Warhol and other pop artists of the fifties and sixties. She wanted to make art that was inexpensive to produce and reproduce, because she wanted as many people to have access to it as possible. Throughout her career at IHC, she integrated religious imagery and texts with the sort of low culture parts and pieces that were staples of Pop Art: corporate logos, and popular music lyrics, and images of common household objects.

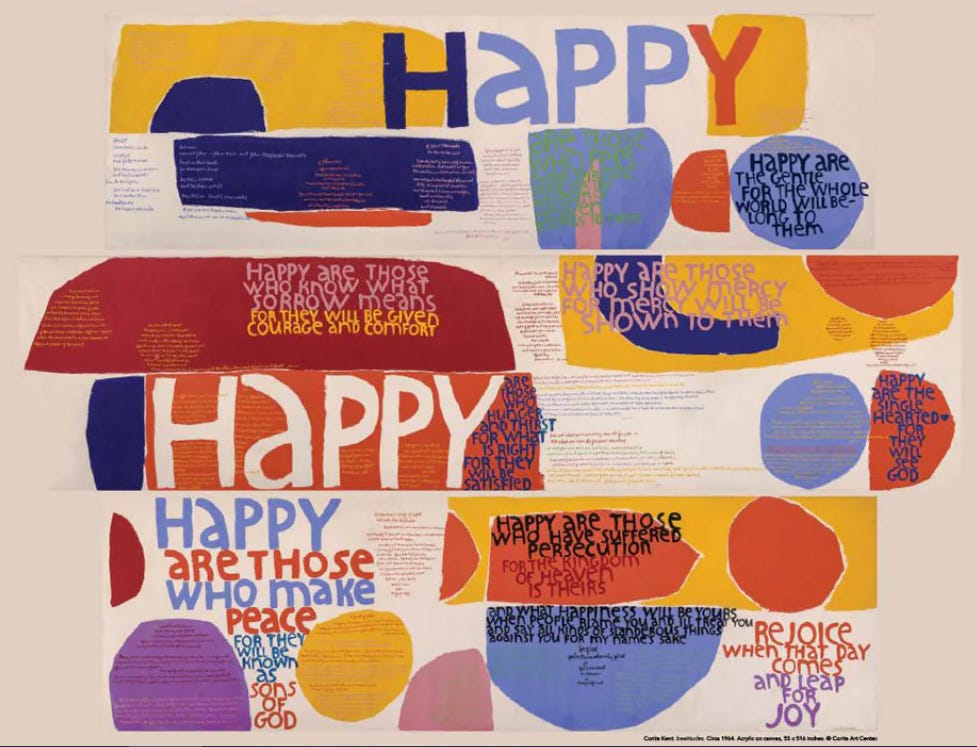

She also received a commission to design a banner of the Beatitudes for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York:

As time went on and American society became more turbulent, Corita’s work started to take on more political messages. Her screenprints started talking more about the hungry people she saw in Los Angeles, and the growing anti-war and anti-racism movements in 1960s America. This was not an uncommon story for a lot of Catholic sisters in the years immediately after Vatican II. They read Gaudium et Spes, they took it to heart, and they welcomed a new era where they could be an important prophetic voice, where being a nun meant more than wearing a habit and blind obedience to the bishop.

Unfortunately, there's another not-uncommon part of this story: even after Vatican II, the actual bishops were still big fans of “blind obedience to the bishop”. Remember, Sister Mary Corita was on the cover of Newsweek and becoming a beloved representative of the church in America, speaking out against unjust wars and inequality in the world. You'll never guess how Los Angeles Archbishop James McIntyre reacted to the new attention given to this sister and artist who was talking about things like love and peace and tolerance, unless you guessed “he was a real dick about it.” McIntyre would frequently butt heads with the sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, eventually gutting their institutions and driving many of the sisters, including Corita, to give up and leave the order entirely. This was also a not-uncommon part of the story for sisters after Vatican II, and how the men who ran the church responded to their hope for the new era of the people of God. Corita asked to be dispensed from her vows after thirty years serving the church.

While she could have kept teaching - and was offered a teaching post at Harvard - Corita Kent still wanted her art to be part of her every day, so she stepped back from teaching for this last stretch of her life, and it ended up being the most prolific era of her career. If you've ever driven by that giant rainbow gas tank in Boston, that's one of hers:

Late in her life, she also designed this postage stamp:

Love is hard work. The only rule is work. If you work it will lead to something. It’s the people who do all of the work all of the time - people like Steve and Alan and Mimi and Joanna and Corita - who eventually catch on to things.

In the past few weeks, there have been several stories in Catholic media that all seem to be calibrated perfectly to make my head explode (and also one - we all know which one - that seems to be calibrated perfectly to make me laugh very hard). I have had trouble coming up with coherent essays to write about any of those stories, and other people I like are doing a better job commenting on those stories anyways. I wrote this instead.

There’s not much reason for me to write this essay, it’s not too relevant to anything that’s going on in the church right now. To my knowledge, four of the people I wrote about aren’t practicing Catholics, and the fifth one left religious life. But I was very excited to tell you about these artists and show you some of their art, and I wanted to let you know that I admire all of these people a great deal, and I love their art, and I love why and how they make their art, and when I think about the kind of person I want to be and the kind of things I want to do or make and the kind of reasons I want to have for doing or making them, I think about these people a lot, and I try and recommit myself to the hard work of love, all of the work, all of the time.

I’m not sure anybody else can do this. Maybe Thomas Pynchon, but we’ll never know, will we?

Like, sorry to get worked up here, but in one of the songs on Have One On Me, which is a two-hour triple album, she references a clock chiming “cuckoo, cuckoo”, and the first “cuckoo” hits at exactly the 1:00:00 mark of the full album! Do you realize how incredible that is! How hard it would be to pull something like that off!