Like You Mean It

You don't need to call it the church's "best-kept secret".

"It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on him not understanding it."

-Upton Sinclair

"Every lifelong Catholic I've ever met is like 'I think we're supposed to give this food to poor people' and every adult convert is like 'the Archon of Constantinople's epistle on the Pentacostine rites of the eucharist clearly states women shouldn't have driver's licenses.'"

-@agraybee on Twitter

If you read the kind of stuff I read and listen to the kind of people I listen to, you have heard some version of the phrase “Catholic social teaching is the church’s best-kept secret.” I’ve said it before. Manhattan College theologian Natalia Imperatori-Lee used it in the recent (and very moving) discussion on abortion policy at Faith in Public Life. Mark P. Shea wrote an entire book where that was the title1. Search "best-kept" on National Catholic Reporter and you'll find dozens of hits for this exact phrase, many of them by Michael Sean Winters, who hasn't had an original idea since 1986.

Now, nobody who has ever used that turn of phrase, including me, has ever meant it literally, it’s always meant more as a dry joke. Nobody thinks there is actually a Cousin Greg-like character at the Vatican going “oh shit, the church wrote down that we have to be good to poor people, I need to shred these documents”2. The way that we usually mean this thing when we say it is that the Catholic church has a rich body of teaching on things like solidarity and workers' rights and the preferential option for the poor, but it's hard for Catholics to even really know about those teachings because Catholics in public life, including and especially our bishops, put such a strong emphasis on things like sexual morality that rigid patriarchy is more likely to get conflated with Catholic identity than, say, being good to poor people. It's not that somebody is trying to keep social teaching a secret, it's just that Catholics hear about all of the other stuff more often and they can easily forget or overlook the social teaching stuff.

But can they really "forget" or "overlook" about the social teaching stuff? Is it a wink-wink dry-joke best-kept secret, or is it, like, a really blatantly obvious thing? Because Catholic social teaching is rooted in scripture, and not like some obscure books in the Old Testament, but some of the most famous Gospel passages of all time, things you hear regularly on Sundays. Catholic social teaching is not the work of an eccentric theologian that a grad student might have heard of; every Pope since the Industrial Revolution has written and spoken explicitly about the social teachings of the church and the church's responsibility to the poor, and the current Pope, who is very good at getting a microphone on the world stage, has written and talked about this a lot. The ideal of a person who lived out things like the preferential option for the poor and solidarity and call to community and care for God's creation and the dignity of the human person is Jesus, who is, like, the Main Guy we build our faith lives around. When I was cross-referencing the pillars of Catholic social teaching to make sure I was naming them correctly in this essay, my main source was the USCCB's own website. Do you really think that any Catholic, who has at any point taken their faith seriously enough to think about it, could honestly say "I didn't know we were supposed to care about poor people or the environment?" Could they honestly say "I just didn't think we had to treat those things as important?"

Is Catholic social teaching really the church's best-kept secret? Literally it's not, but figuratively, I don't think it is either, and that's why I'm starting to chafe whenever I hear that "best-kept secret" turn of phrase, and why I want to get away from it. It's not a secret. It's not unknown. It's not obscure. It's not something the church forgot. It's a big, loud, obvious piece of Catholicism that stares you right in the eye every day you decide to be Catholic. What would drive a Catholic to willfully ignore a big loud obvious piece of Catholicism? That's probably not a very hard or even interesting question to answer, you've probably already come up with some answers yourself. But here's a much more interesting question to me: what would drive someone to join the church while willfully ignoring that?

I've never converted. I was born Catholic, still am, and I think if I were to join another church I would have done it a long time ago, so I'm pretty sure I'm stuck here forever. Now, I certainly can understand why someone would leave the Catholic church for another faith tradition, but it's not something I've ever been able to do personally. I mean, it would be an enormous decision with significant ripple effects: my wife and kids are Catholic, my kids go to Catholic school, my entire extended family is Catholic, I went to a Catholic grade school, high school, and university, I got a theology degree at that Catholic university, I continue to read whatever Catholic stuff I stumble across. Catholicism has been fully entangled with every area of my life for over three decades; choosing to convert to another religion would fundamentally change my relationship to every part of my life and identity and every person I am close to. Choosing to convert would be a decision, I think, on the same scale as choosing to get married or choosing to become a parent. It would be a monumental, permanent change that would affect everything I do. I have not reached a point in my faith life where I want to make a decision on that scale.

And, on top of that, there's like, a lot that can go into the formal process of conversion, if it's anything like joining the Catholic church through RCIA. That is a months-long process. Somebody has to sponsor you. You go to classes, you fill out paperwork, you read catechetical matetials, you start going to Mass but only specific parts of the Mass. It's a lot a time and a lot of work! So if you want to convert from one religious tradition to another, you have to really mean it. It is a hard and serious thing, the kind of thing you only do maybe - maybe - once in a lifetime. That's why it's so interesting to me that Abby Johnson has converted twice.

Abby Johnson is a former Baptist and a former Episcopalian, or at least that's what this chyron said on EWTN in 2014:

I don’t like to make assumptions or speculate on why someone changes religions, which is ultimately a very personal decision; the only time I would ever make an exception to this rule is when somebody does multiple hour-long EWTN interviews explaining the exact reasons why they converted, so here we are. We already talked about this interview before, but to summarize: Johnson was raised Baptist. As she grew in her career as a clinic director at Planned Parenthood, she decided to leave the Baptist church of her family, because she disagreed so strongly with her church's hardline views on abortion that she had to find a religious tradition that would be a better fit for her, one that would allow her to continue to do her job without conflict of conscience or cognitive dissonance. So she converted to Episcopalianism. Then, when she later decided to leave her job at Planned Parenthood to become a right-wing media personality decrying Planned Parenthood, she once again had to leave her church so that she could do her job without having to deal with disagreements from her church community. So she became Catholic.

I want to note here that I'm not really putting words in Johnson's mouth, and I'm not really taking words out of her mouth, either. You can go and watch the interview, but these are the reasons she gave to the EWTN guy for converting, twice. It was about abortion and Planned Parenthood, and there's not much else there. There's no discussion of theologians or other church teachings that drew Johnson into either the Episcopal or Catholic churches. She didn't marry into either of these faith traditions. She didn't talk about the liturgical or ritual life of the church; in fact, during the interview she talks about how she doesn't see a meaningful difference between Episcopal and Catholic liturgy, which, coming from anybody else, would make an EWTN anchor's head explode3. If you’ve seen or read Unplanned, which is not a movie or book I’d broadly recommend, Abby’s character is religious, but not specifically Catholic, she’s just someone who goes to church and her religious identity doesn’t need to go any deeper than that, the important thing is that she’s somebody fighting Planned Parenthood.

Like I said, conversion is a big deal. You have to mean it. It’s a monumental, permanent change that affects everything you do and how you relate to everyone in your life, and it comes with a lot of paperwork and meetings. Abby Johnson’s conversions aren’t about changing religions, they’re about changing her job. Changing religions - twice - happened downstream from all of that. Doing the job came first.

And it is a job, to be clear. Johnson makes her money by speaking. She speaks at venues and events that are explicitly Catholic, like when she spoke at the Catholic University of America shortly after being in a mob that tried to murder the sitting Vice President, or her upcoming keynote address to the “Coalition of Canceled Priests”, which appears to be made up of priests who are into QAnon conspiracies, and not priests who are “canceled” because of the other thing you’d assume priests would get canceled for4. If she wasn't Catholic, she wouldn't be considered for a lot of these gigs in the first place.

This is all to say: what if there is a way that some people choose to be Catholic where being Catholic is, first and foremost, a job?

On April 26, shortly after Tucker Carlson got fired, right-wing Catholic journal Crisis Magazine ran “What Should Be Tucker Carlson’s Next Move? How ‘Bout Becoming Catholic?” a headline which made me say, out loud, in a room by myself, “hoo boy here we go”.

Putting aside how unbelievably funny it is that S.A. McCarthy published this piece after Carlson got fired, and after it became clear that more information was going to come out that was going to make him look bad, but before any of it - the overtly racist texts, the sexual harassment - actually did come out, I realize we haven’t actually talked about Crisis before and what their whole deal and history is. They’re a Catholic magazine that will gladly run pieces about how Tucker Carlson should become Catholic; there, you’re caught up on their whole deal!

So why should Carlson, a lifelong Episcopalian who does not appear to have ever publicly expressed interest in converting to Catholicism, join the one holy Catholic and apostolic church? The answer is simple, according to McCarthy: based on a speech Carlson recently gave at a Heritage Foundation event, he hates all the same things we hate:

“Much of the requisite ideological groundwork for Carlson’s conversion to Catholicism is not only laid but deeply ingrained in him…Carlson addressed the “theological” war being waged in America and, indeed, throughout the West today. Carlson’s description of that war aligns with an orthodox Catholic view of the same…Speaking of the old form of policy debates, Carlson said, “There is no way to assess, say, the transgenderist movement with that mindset. Policy papers don’t account for it at all.” This is not a matter of two groups seeking the common good but with differing ideas of how to achieve it; it is two factions at war, with little or no common moral ground. Carlson continued, “If you have people who are saying, ‘I have an idea, let’s castrate the next generation. Let’s sexually mutilate children.’ I’m sorry, that’s not a political debate.” During his Heritage speech, Carlson defined abortion today as “human sacrifice,” a notion not uncommon in Catholic theology. “If you’re saying that abortion is a positive good,” Carlson explained, “what are you saying? Well, you’re arguing for child sacrifice, obviously”...The Catholic Church, according to Vlaardingerbroek—and according to every saint throughout the Church’s long and storied history—is the sole force with the strength, competence, and authority to win the war against evil…Since Tucker Carlson sees the same war Vlaardingerbroek, the saints, and the Catholic Church do, raging over the course of history and reaching an unprecedented stage today of dichotomous savagery, I sincerely hope his commitment to side with good over evil leads him into the open arms of the one, holy, Catholic, and apostolic Church.”

Let’s put aside that this ran a week and a half before we learned that Carlson likes texting people about “how white men fight”, and let’s put aside that if you still think that Carlson says things out of conviction and a sense of genuine belief, you’re a fucking mark. Instead, think about why people convert; if you know someone in your life who joined the Catholic church as an adult, think about why they converted. Maybe they got married, I know several people who, for example, married a Catholic and converted as part of the process of preparing for their wedding and their marriage. I know people who were not Catholic before they went to college, then got soaked in Catholicism at my Catholic university and were drawn to the rituals and the traditions and the culture and the teachings. Do you know a lot of people who made the decision to convert, who decided to go through the months-long process of joining the church and finding a sponsor and sitting in catechism classes in the parish multi-purpose room, so they could hate trans people more efficiently? To McCarthy, this is what Catholic identity is. It’s about fighting child castration and child sacrifice, it’s about joining a literal army, and Carlson is already saying and doing the right things to hurt the right people. He’s already doing the job. And McCarthy definitely sees Catholicism as a job, he positions Carlson’s hypothetical conversion as his “next move”, as a career move, prompted by Carlson having to find a new job after leaving Fox. Tucker, do you want a job? I’m sure we can get you a speaking gig at the Coalition for Canceled Priests. How ‘bout?

In an interesting sort-of coincidence, the day after that Tucker Carlson piece ran at that shitty Catholic magazine, a better Catholic magazine (Commonweal) ran “The Rise of Religious Disaffiliation” by Loyola Marymount theologian Brett C. Hoover. Where Crisis asked “can we please convince this shitty person to become Catholic?”, Commonweal asked “why are so many people deciding to become not-Catholic, and does it have to do with all the shitty people here?” Hoover was looking at the well-documented growth in “nones” - people who, while not necessarily message-board atheists, do not claim affiliation with any religious traditions - over the past three decades, and was careful to point out that this is not just a worrying trend in civil society and culture, it’s an extremely worrying trend in religion. It’s not just that people changed, what being “religious” means changed too:

“The opting-out increased dramatically from 1990 on. We might wonder, as one of my students asked rather frankly, “What in the hell happened in 1990?” What did not happen was that the United States suddenly became more secular. But the strong association between Christianity and conservative politics became more visible in the media during those years, when Evangelical leaders became hyper-focused on opposing the growing public acceptance of LGBT people and same-sex relationships…many Americans simply decided that if being religious meant being conservative (and condemning LGBT relationships) then they could not consider themselves religious…

The marriage of Evangelicalism with Republican conservatism (which extended to many churchgoing white Catholics) eventually became so seamless that religious identity seems increasingly articulated in terms of partisan policies. During the 2020 election, a very devout priest I have known for many years defended his support of Donald Trump with Republican talking points, eschewing any significant reference to Catholic teaching. For many Catholics today, Catholic identity is measured less by doctrinal orthodoxy or a commitment to Christian discipleship fostered by a sacramental sensibility, and more by a political purity free of even the slightest association with the political Left. My own Catholic university’s efforts to educate and resource Catholic pastoral leaders, to practice Jesuit pedagogy, to foster the moral formation of undergraduates, and to publicly critique the structures of injustice in our society are deemed by many Catholics to be largely irrelevant to its Catholic identity.”

This makes sense to me. In my lifetime, there’s been a clear trend where “becoming religious” gets increasingly conflated with “being conservative” (or “voting Republican” in the case of many religions including Catholicism). The Catholic church didn’t write new doctrine to get here - plenty of their rules are shitty but they have been shitty for much longer than 30 years - but they did change how they talked about doctrine and how it should relate to political engagement. And a large part of what enabled that was a rapidly developing media landscape, where it was easier to express your political beliefs and say “and that’s what it takes to be Catholic”, even if you were talking out of your ass. If you were, say, a priest who was a huge fan of George W. Bush, you could rustle up the money and resources to start your own terrible conservative magazine in the 1990s, and the church or media structures that allowed you to do that weren’t really around before then. If you were an out-of-work professor, you could start your own YouTube show in the 2010s about what “real” Catholicism was and why the Vatican was actually trying to tear it down, and there would be nobody to stop you; before that era in media, there would have been plenty of people to stop you. If you had been fired from your job at Planned Parenthood, you could get interviews with Bill O’Reilly or write columns for The Federalist or do interviews with Taylor Marshall or sign a film deal with Pure Flix, and all of those avenues for making a living are new in my lifetime, and they all affect people’s perception of the Catholic church. If you were one of the Wile E. Coyote figures in the far-right like Kaitlin Bennett or Ali Alexander or Milo Yiannopolous, you could decide to make Catholicism a loud visible part of your identity, which would suddenly start getting you new interviews and new income and new attention; as David Lafferty commented to Salon on folks like these three idiots:

"When you tap into the ecosystem of online Catholicism, you've got a built-in audience with big traditionalist or ultra-conservative Catholic sites, all of which have very devoted followers and fan bases. If you're coming from the populist right into the church, you're going to be able to walk right into that world and become a sort of instant celebrity."

A conservative Catholic journal begging a white nationalist Fox host to join the church mimics this pattern, although I don’t think it would play out the same way since Tucker Carlson isn’t some grifter scrambling to find his next paycheck, he’s a very rich man from a very rich family who will land a show somewhere else very quickly. But you can pretty easily track this increasing growth in media outlets that support the overarching project of “oh, you’re a huge piece of shit, we can find a Catholic audience for you if you’re willing to come on board”. Now, this all doesn’t explain everything about the rise of the “nones” - obviously, abuse scandals and the damage to institutional authority and reputation would have also played a very big role over the past several decades - but it definitely explains something that’s not insignificant. People kept getting new loud megaphones to say “being Catholic means being and supporting some truly awful people”. Saying those things is a job. As long as people can keep making money saying those things, they’re going to keep saying them. And that turned a lot of people off to Catholicism and Christianity, and that seems pretty understandable. Nobody wants to spend the time explaining “yes, I’m Catholic, but to be clear, I’m not an awful person like all of the Catholics you see on One America News or Twitter or, uh, at the USCCB conference, I’m like the kind of Catholic that likes helping people, feeding the hungry, visiting the imprisoned, that sort of thing. I know, I know, it’s our best-kept secret.” Which, again: it’s not a secret.

I don't know, guys, I don't know how blunt I can be about this. There's a passage in Matthew's Gospel, like a very famous passage that a lot of Catholics know, where Jesus - God Himself - says, pretty directly, words to the effect of "if you feed hungry people I will let you into Heaven and if you don't feed hungry people I will not let you into Heaven." I don't have very much I can add to that about how Catholics should think about their faith, and what they should think about Catholics in the media who seem to espouse the complete opposite of this, and whether they are espousing this because they've thought seriously about their faith, or if they're just getting paid to do a job.

I guess I would add this: if you are the kind of Catholic who thinks that your faith obligates you to care for the hungry and the stranger and the imprisoned and the sick and the naked, you are not "keeping a secret". You are not practicing some sort of obscure indie-rock version of Catholicism, you are not watching some up-and-comer play an acoustic set at a tattoo parlor right before they hit it big. You are at Lollapalooza, watching the headlining set by the Killers, and they just came out to do "Smile Like You Mean It" for the second encore. This is real mainstream shit, guys. We can act like we know this is the way Catholicism is supposed to be.

But maybe there's one other thing here that's worth exploring: when Jesus said that thing which is not a secret but in fact a big loud obvious piece of Catholicism, He added one interesting piece: He said that when you help those people, you're helping Him. He's the hungry person, He's the naked person, He's the imprisoned person, He's the stranger in need of welcoming. And that can lead you to another question pretty quickly: if we, as Christians, aspire to be like Jesus, and if Jesus is the poor and suffering person right in front of us, are we supposed to be poor too? He is someone who chose to share in the worst suffering of humanity, is that someone we should aspire to be as well? Precarious, poor, unwelcome? If Catholicism isn’t supposed to be a job, could it be the absence of a job? What if "be a poor person" is the church's actual best-kept secret, more of a secret than "be good to poor people?"

Journalist and Catholic Worker Reneé Roden writes a substack on Catholicism that is much better than mine, and I'm sorry if you're just finding out about this now. She ran a short piece in February titled "Quit Your Job" that I am still sitting with:

"I wish priests just told young people to quit their jobs and do what they thought would be the best thing for them to do to make the world a place where it is easier to be good and where the common good is less uncommon.

I wish someone had told me sooner to quit my day job and to rejoice in being poor, and that, in doing so, I would find community. I wish the Church could assure me that if I were to become poor like Christ, like the Eucharistic Lord, I would not be left alone, but find myself embraced by a fellow company of impoverished members who shrug off the “good life” as portrayed in advertisements, Instagram posts, and embrace a different sort of living…I wish someone told me that saints depend upon the providence of God, not in theoretical, spiritual, or emotional ways only, but in very physical, material ways.

And that is not something that is only for crazy people, but it is a viable mode of existence for all Christians. And is, in fact, the only compatible mode of existence with Christianity.

I wish someone had told me—and I wish someone would tell the young people filing into church pews on Ash Wednesday—that serving God and rejecting Mammon were full of joy.

And I wish that someone had taken me out of my theology school classroom and into the streets and said: the least of these are not only the treasures of the Church, but the Church’s theology as well. If you wish to know and understand what the Church’s message and mission has been over the course of two millennia, go to the poor and don’t serve them, but be one of them."

I have not quit my job yet, but there's a very simple reason for that: I am a coward. I have a lot of work in front of me before I can be the kind of Catholic I should be, but I hope I can be that kind of Catholic someday. Roden's radical message is very challenging to me, because I'm pretty sure she's absolutely correct, and she lives in a Catholic Worker community and I don't. Choosing Catholicism is not choosing a job, it is not constructing a public persona to hate the same things as your friends, it is not choosing speaking gigs or online notoriety or university fellowships or cable news shows or or or whatever else makes us feel comfortable and powerful. Choosing Catholicism is choosing obscurity and instability and pain and unwantedness. So you really have to mean it. The social teachings, the helping people stuff? That's not a secret, that all goes without saying. It's making that next choice that is the real leap.

I will say that there is one funny thing about the social teaching of the church and "best-kept secrets": the formal social teaching of the church was, apparently, a literal secret to the founder of the Catholic Worker movement.

We've talked about this a little before, but Dorothy Day did not convert to Catholicism because she was trying to get a cushy media gig. But she also didn't convert because she really admired what the church taught about serving the poor, the poor that she had already been serving with and fighting alongside for years. She was pretty clear, in her memoir The Long Loneliness, that she wasn't even aware of the church's social teaching when she became Catholic:

"...a priest wanted me to write a story of my conversion, telling how the social teaching of the Church had led me to embrace Catholicism. But I knew nothing of the social teaching of the Church at that time. I had never heard of the encyclicals. I felt that the Church was the Church of the poor, that St. Patrick’s had been built from the pennies of servant girls, that it cared for the emigrant, it established hospitals, orphanages, day nurseries, houses of the Good Shepherd, homes for the aged, but at the same time, I felt that it did not set its face against a social order which made so much charity in the present sense of the word necessary. I felt that charity was a word to choke over…It is natural for me to stand my ground to continue in what actually amounts to a class war, using such weapons as the works of mercy for immediate means to show our love and to alleviate suffering...Going around and seeing such sights is not enough. To help the organizers, to give what you have for relief, to pledge yourself to voluntary poverty for life so that you can share with your brothers is not enough. One must live with them, share with them their suffering too."

Day did not join the church because they told her how to treat the poor; Day joined the church because that's where all the poor people were. That was why she converted. She made a decision about what she wanted to be, and who she wanted to be around; that’s what conversion is. Day didn’t want to be around people who would pay her for speaking gigs or vote for her favorite politicians; rather, her decision was drawn from the desire to respond to the suffering right in front of her, and it led her to "this is where the poor people are, and I need to be one of them". Dorothy Day and Abby Johnson were both Catholic converts, but to make a controversial-yet-brave statement, I think Day was a little better at it.

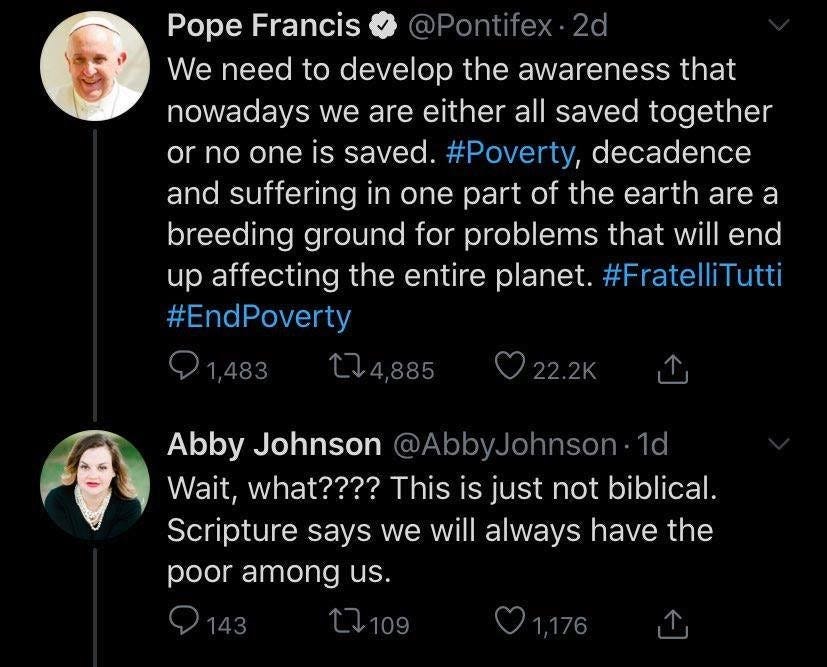

Speaking of Abby Johnson, do you remember this one? This is from a little less than three years ago:

So, when Johnson was, uh, correcting the Pope, she was pointing to a famous line, also spoken by Jesus, in John's Gospel. You probably know this one, too, it's even adapted and dramatized in Jesus Christ Superstar5. Jesus and the Apostles visit Mary and Martha, Martha bustles around the kitchen to get everything ready, Mary just sits and hangs out with Jesus and eventually perfumes his feet. Judas Iscariot - the original fabulous killjoy - yells at Mary for spending the money to make Jesus feel a little more comfortable, and Jesus responds:

"Judas Iscariot, one of his disciples (he who was to betray him), said, “Why was this ointment not sold for three hundred denarii and given to the poor?” This he said, not that he cared for the poor but because he was a thief, and as he had the money box he used to take what was put into it. Jesus said, “Let her alone, let her keep it for the day of my burial. The poor you always have with you, but you do not always have me."6"

So there you go. She figured it out. Abby Johnson cracked it when Pope Francis couldn't. Jesus said "the poor you always have with you", so there's no need to care about those stupid filthy poors, much less try to help them, much less aspire to be one of them. The idea that we must be saved together? The idea that poverty will cause more problems in the world if we just let it continue? The fact that the passage explicitly states that Judas’ comment was not made in good faith and pretty clearly impies that Jesus was saying something other than “we don’t give a shit about the poor”? Well, that's stupid and not biblical. Who are you going to trust, the Pope who worked with Argentina's poor for decades, or the woman who joined the church after the last Shrek movie came out?

I mean, it's certainly not like there's any other way to interpret this passage, no other way you can possibly read this besides "Christians are not supposed to care about the poor". If there is any other way to interpret it, the church is probably keeping it a secret. There's no field of New Testament scholarship that could possibly have looked at this more closely. There's no other interpretation of this line, certainly not a famous one, certainly not a famous sermon delivered by one of the most famous American authors of the twentieth century and a guy that I quote all of the time and the sermon is easily available online and also was collected in a book of essays which has been in print continuously for forty years and you can just go to the library and find a copy right now? Right?

"I, as a Christ-worshipping agnostic, have seen so much un-Christian impatience with the poor encouraged by the quotation, ‘For the poor always ye have with you.’ I am speaking mainly of my youth in Indianapolis, Indiana. No matter where I am and how old I become, I still speak of almost nothing but my youth in Indianapolis, Indiana. Whenever anybody out that way began to worry a lot about the poor people when I was young, some eminently respectable Hoosier, possibly an uncle or an aunt, would say that Jesus himself had given up on doing much about the poor. He or she would paraphrase John twelve, Verse eight: ‘The poor people are hopeless. We’ll always be stuck with them.’ The general company was then free to say that the poor were hopeless because they were so lazy or dumb, that they drank too much and had too many children and kept coal in the bathtub, and so on."

It turns out that Abby Johnson was not the only person to read that Bible passage and think "perfect, I can finally stop thinking about the poor". It turns out she had not figured out anything new. A lot of Kurt Vonnegut's aunts and uncles thought that they had cracked it too, and Vonnegut talked about it in a very famous 1980 Palm Sunday sermon he delivered at St. Clement's Episcopal Church in New York, later reprinted in his essay collection Palm Sunday.

Vonnegut wanted to revisit this passage from John’s Gospel and see what Jesus was really saying, because he had a pretty good feeling it wasn't "don't worry, poor people don't matter". I like Vonnegut's new theory, which is that Jesus, who knows where things are heading and that He has about five days left before suffering and dying, and who just heard the man whom He knew was going to betray Him condemn the woman who was making Him feel a little bit better for half a second, on something that Judas didn't really care about in the first place. So maybe, just maybe, Jesus rolled His eyes and made an offhand dry joke to, as politely as He could, tell Judas to shut the hell up for once in his life:

"This is too much for that envious hypocrite Judas who says, trying to be more Catholic than the Pope: ‘Hey-this is very un-Christian. Instead of wasting that stuff on your feet, we should have sold it and given the money to the poor people.’

To which Jesus replies in Aramaic: ‘Judas, don’t worry about it. There will still be plenty of poor people left long after I’m gone.’

This is about what Mark Twain or Abraham Lincoln would have said under similar circumstances.

If Jesus did in fact say that, it is a divine black joke, well suited to the occasion. It says everything about hypocrisy and nothing about the poor. It is a Christian joke, which allows Jesus to remain civil to Judas, but to chide him about his hypocrisy all the same."

Was Abby Johnson, the woman who joined the church because it was what worked with her job, 'trying to be more Catholic than the Pope'? I mean, she did literally respond to him on Twitter to tell him he was wrong to care about poor people. But that was no flash of insight on her part; people have been misinterpreting that specific line of the Gospel for (at least) decades. Which means that people have been responding to that misinterpretation for decades, although Vonnegut’s response is certainly one of the more famous ones. There's nothing left to crack here. This Gospel passage is not some sort of trump card that assholes can play to square their asshole-ness with their Christianity. We’ve already seen this. We're still supposed to care about poor people. We’re still supposed to want them not to be poor anymore. That is not a secret the church is keeping from anyone.

Maybe Jesus was making a dry joke, as Vonnegut suggested. But amateur comedian that I am, I would like to punch up that dialogue a little bit. I like to imagine, in that moment, Jesus deadpanning "Oh really Judas? That’s what you’ve been thinking about? You were just really worried about giving that money to the poor? You're going to fix it all with the perfume money? That's what's going to put you over the top, finally? You were just really struggling to find that last piece that was going to solve poverty and it was going to be the perfume money? Tell you what, I’m going to be dead in less than a week and then you’ll finally have the chance to finish that big ‘give our money to the poor’ project that I know has always been your top priority, how does that sound?" And maybe Judas would have felt a little bit ashamed by this, a little bit uneasy about what was going to happen next.

I think Jesus knew that thousands of years after His crucifixion, people would read the story of Him and Judas and Mary, and read it while there were still poor people around, and maybe start to feel a little bit ashamed that we do always have the poor with us, that we still haven’t done enough for the poor who are with us, long after we were given pretty direct instructions about how important it was for us to do that. But having the poor with us means we still have Jesus with us, too, which could, perhaps, give us another option than just condemning the people who try to address the needs right in front of them. We could, if we really felt like being radical, make a big decision about what we are and who we want to be around, a decision drawn from the desire to address the suffering right in front of us, a decision that led not only to helping the poor but choosing to become one of them. We could - if we needed to give a name to this process - convert, like we mean it.

Shea, whose writing I generally enjoy, has been kind enough to reference a few of my pieces on his blog, and one of his commenters once pointed out that I had, in one of my essays, misspelled the name of Lord of the Rings character King Theoden, which is as good an explanation as any for why I don’t allow comments on my own site.

At this point in the draft I opened a separate Google doc and titled it “Pilot_draft 1” and then wrote on a Post-It “WOULD SARAH SNOOK PLAY A SEXY NUN?”

Which is perhaps a reason to start dropping the phrase into casual conversation.

Like, I don’t want to spend too much time on this, but come on guys: imagine bragging to people “yeah I used to be a priest, but the church said I was too DANGEROUS” and not realizing what everyone is going to immediately assume.

Although that musical puts Mary Magdalene at the center of the scene, while the Mary in the actual biblical story is a different Mary, the sister of Lazarus. I assume Weber amalgamated the characters for simplicity’s sake, because let me tell you there’s a bunch of Marys in that Bible and keeping them all straight is kind of a chore.

This is the Revised Standard translation, which was the translation used in the homily I’m about to cite in the next section of the essay.