"I never expected much of the bishops. In all history, popes and bishops and abbots seem to have been blind and power-loving and greedy. I never expected leadership from them. It is the saints that keep appearing all through history who keep things going."

-Dorothy Day, 1968

"That's the way people try to dismiss you. If you're a saint, then you must be impractical and utopian, and nobody has to pay any attention to you. That kind of talk makes me sick."

-Dorothy Day, 1977

PART ONE

Back in the summer of 2014, I was at a parish in Chicago with a very large population of young adults who were active in parish life; the parish could get like 300 people a week for Theology On Tap out on the church lawn during the summer. One of these evenings, the speaker gave a talk on Theology of the Body, and at one point said "this sounds kind of silly, but I do think there's a case to be made for John Paul II to someday be remembered as the patron saint of sex," and she kind of chuckled at that, but her point was that JPII, who had just been canonized a few months earlier, had taught about human sexuality so eloquently, that - what a beautiful irony! - the celibate pontiff would be remembered for his enduring legacy on sexuality.

Later that evening, we had to end the outdoor session abruptly because a guy on the street saw all 300 of us sitting in front of a Catholic church, interrupted the speaker, and started screaming angrily from the sidewalk about how the Catholic church was a disaster due to the abuse crisis. We had to end the talk early. The pastor had to step in. It was a really uncomfortable situation. The parish moved the next week's Theology On Tap to inside.

Just to state it outright: the guy on the street was right and the speaker was wrong.

2014 also saw the release of the documentary film The Overnighters, directed by Jesse Moss and winner of the Special Jury Award at Sundance. I watched it when it was first released, and I just re-watched it before writing this piece; it is, in my opinion, one of the greatest films ever made about Christianity, so suck on that, Babette's Feast. As of this writing, the film is streaming for free, with ads, on a few services including Tubi, Kanopy, and Pluto; you should go watch it right now before reading my detailed description of everything that happens in the movie. I don't have any real time-sensitive reason to write an essay about the movie, so I'll go with this: it's set in North Dakota and that's a very important state to G.O.T.H.S. because it's one of five states where I've never had a single reader, according to Substack:

This means I can spend a short paragraph making fun of how shitty a state North Dakota is and be reasonably confident that I won't face any backlash. Hey guys, how's your shitty state?!?!?! You all enjoying Mount Rushmore? Oh wait, that's the good Dakota! Well, at least you can get a drink of water from Wall Drug - oh wait, that's the good Dakota too! Well at least Doug Burgum has a real shot at becoming president thanks to all of the people who have heard of him1.

In all seriousness, here's something North Dakota did have in the late 2000s and 2010s: a massive oil boom and rapid expansion of hydraulic fracking in the Bakken shale formation. I don't understand how all of that really works, but here's something much easier to understand: all of a sudden, in North Dakota in 2008, there were thousands and thousands of jobs available in the fastest-growing economy in America, easily paying six figures and requiring no advanced degrees or complex prerequisites. While other industries were in recession, tens of thousands of men showed up in North Dakota overnight to work on the oil rigs. Take the beginning of Grapes of Wrath, rotate it ninety degrees, and you get the idea: a mass migration North, by men desperate for jobs, to a place that doesn't exactly want them there. I live in a city of three million residents, and if tens of thousands of people showed up overnight, it would be incredibly inconvenient for our city. But when tens of thousands of people show up in North Dakota, entire cities and counties double in population before they're able to build additional sewer lines or highway lanes or water towers or, most importantly, houses. Tens of thousands of people overwhelming these towns and remote little outposts in a remote little state, and there are literally not enough buildings to hold them.

That brings us to Concordia Lutheran Church in the tiny town of Williston, run by pastor Jay Reinke. In a two-year period in the late 2000s, over one thousand men were housed in Reinke's church, with hundreds more sleeping in their cars in the parking lot. They needed a place to sleep, Reinke had pews and floors and cots. There were people in front of him who needed help, and he helped them. It was, to Reinke (center in the photo below), a question of “who is my neighbor and how do I serve them?”

For the large majority of The Overnighters’ runtime, if you care about the stuff that I care about, you will be saying to yourself “this is the real shit right here”. This is it. This is radical hospitality. Reinke did not say no to anybody who came to his door, didn’t say no to anybody with a criminal record, didn’t say no to anybody who looked dirty, didn’t say no to anybody who was foulmouthed or rude, didn’t say no to anybody because they can’t kick you out of the city of God. He appears to have been busting his ass twenty-four hours a day, the whole time while always giving, hooking men up with job placements and food and leads on more permanent housing, all to people that the rest of his town, and in fact the rest of his state, are trying hard to ignore. To paraphrase Saint Ignatius, Reinke gave and did not count the cost.

And the cost, to be clear, is significant. Reinke barely sees his wife and three children; as he puts it, “I’m not as involved with my wife or my children as I need to be, because I'm preoccupied”. The regular churchgoers at Concordia don’t all want unhoused migrants sleeping in their pews overnight and start to chafe against Reinke’s decision to shovel out unqualified charity; Reinke’s wife worries that “the church will call into question my husband's dealings with the guys,” although Reinke prefers the term “judgment” to “dealings with the guys”. But most importantly, the town of Williston is done with giving any sort of aid to the migrants coming into their towns looking for work. Crime rates are up, resources are being depleted, and the town council is just looking for any solution to get rid of these outsiders. Reinke himself says “it does amaze me that giving people floor space is provocative,” and he even has some of the overnighters crash in his own basement, but this is, indeed, all provocative for the people of Williston, who are very resistant to change.

But even the actual people that Reinke helps seem to abruptly chafe against Reinke’s unconditional love in this harsh environment, and maybe that’s just just a side effect of them being in this pressure cooker. One of them snaps that “He begged me to stay with him, then he threw me out in four days,” when Reinke has to make room for another overnighter who can’t stay in the church. Another one, on his way out of town after he gets arrested, snarls at Reinke that “you brought me really close, pastor, and then you pull your crap. You lie by deceit…I've got no more respect for you,” and it really just comes out of nowhere. Other stories that seemed inspiring in the first half of the film - people getting jobs, moving their families out, building homes, turning lives around - turn to ash as addiction and criminal records and human frailty rear their heads. But at every turn, Reinke says the right thing. “"Nobody's good at loving, but we have to do it anyways.” “Everybody is bearing a burden.” “This is a church, this is a place where sinners should come.” When the city council eventually uses a fire code regulation to permanently shut down the church’s shelter program, Reinke asks “are we even a community?” One overnighter - a sex offender that Reinke shelters in his own home because he can’t have a sex offender listing the church as his address - is outed by the local paper and about to get kicked out by the congregation, and he asks Reinke “what is the church even for anyways?” It’s for the salvation of sinners and bringing people to Jesus, Reinke says, and the overnighter all but says “well there you have it”.

Think about the world we live in now - a world with a very different but no less urgent migrant crisis - and how badly it needs radical hospitality, how many of us try to ignore the suffering in front of us, how many people in power tell us that we shouldn’t have to care about that suffering, how many of those suffering people have no lifelines, nowhere to turn to, and this man risked his reputation and his job to just be there for them, to give them whatever he had. You cannot just find people who are willing to do this, and Reinke did it. It is nothing short of sainthood in the contemporary era.

Until.

In the final minutes of The Overnighters, after everything has collapsed, after the program has shut down at Concordia, after the congregation has all but told Reinke that they’re sick of him, Reinke does a talking head interview to the camera where he breaks down and explains that he can’t keep lying anymore. He confesses that he’s “struggled with same sex attraction…and I've acted on that…I'm the one who's broken.” It’s such a weird confession after ninety minutes of this exercise in hospitality that you briefly wonder why it is at all relevant to what you just saw. Until you realize, with rapidly dawning horror, that it might be the only thing that’s relevant to what you just saw.

Reinke was taking care of hundreds of men, men over whom he had tremendous power, including the ability to provide or withhold security, resources, and leads on jobs, and after 90 minutes of watching him do all of this, you just learned that he's been having a lifelong struggle with his sexual orientation. You start to realize that the men who snapped at Reinke out of nowhere maybe weren’t snapping out of nowhere. You realize that Reinke’s correction of “dealing with the guys” could have been motivated by more than semantics. Reinke’s reassuring the men “hey, we’re all broken” or apologizing to his wife for being preoccupied with the guys at the church suddenly all look very different. You don’t know which parts of the movie were motivated by Christian charity and which parts, if any, were motivated by more skeezy reasons, but you now know that any of it could be skeezy. And this is hard, because you just spent the last ninety minutes watching this guy do what you absolutely could not do and what most people absolutely cannot do, except that he may not have actually been doing it for the best of reasons, he was definitely cheating on his wife and the mother of his three children while he was doing it, and that the best-case scenario is that he did this partially to assuage his internal guilt. You can't get around the fact that Reinke did, in fact, help a lot of people, people who would have had nowhere else to go if Reinke hadn't been running the Overnighters program out of the church. But you've dismissed and criticized far more celebrated people than Reinke, including literal saints like the one I mentioned at the top of this essay. Reinke is not a saint, but if he's not a saint, who the hell could even be a saint to begin with?

PART TWO

As baptism gifts, my daughters got multiple children’s books of Lives of the Saints, a Saint A Day book for children, that sort of thing. Another gift was a little book of six cardboard jigsaw puzzles of six pieces each with pictures of the saints; inexplicably, the publisher of this book sought out and received a nihil obstat and imprimatur from the local bishop to assure me that the six-piece jigsaw puzzle with a cartoon drawing of Saint Patrick was reviewed by a professional theologian and found to be free of doctrinal error:

Weird though that is, these were still very nice gifts, because we like the saints. "We" here broadly means "basically all Catholics", of course, but I also specifically mean "Catholics who have found themselves frustrated by the other bullshit in the church". Exclusion of marginalized groups, stupid political moves, bishops who let power go to their head, the abuse crisis, we tend to see the saints as separate from all of that. The saints come from all parts of the world, all types of lives, all levels of power in the church; there is such a broad variety of stories of sainthood in our church. And perhaps because of the thousands of varied lives that have found their way to sainthood, the saints give us hope when our church lets us down; Dorothy Day, perhaps a future saint herself, is quoted at the top of this piece speaking to how the saints give her reassurance when she got frustrated with the church’s leadership which, based on her writing, was basically all of the time. Even when we don't feel at home in the church - usually for extremely good reasons - we know that there have always been people who have done the right things, who have lived lives of holiness, who can inspire us to live lives of holiness as well. When the church infuriates us and when our identity as Catholics weighs on us, we can always lean on the saints, on the people that God chose to lead extraordinarily holy lives.

Of course, we might want to ask how someone becomes a saint in the first place, just to make sure it is the work of God and not actually a weird fragmented process run by a comically large number of people working at every level of the church, with each person bringing in their own conflicting narrative and political objectives.

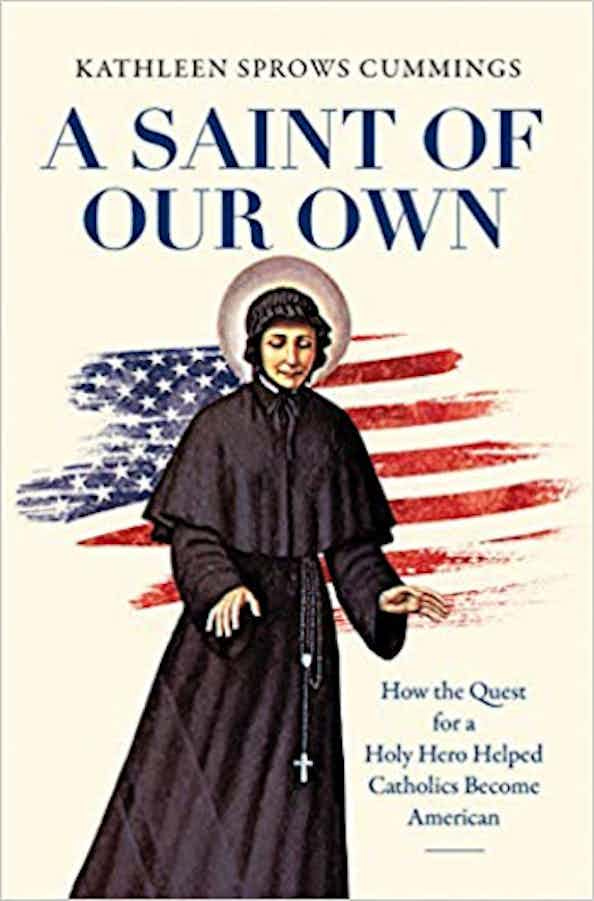

Earlier this year I had the chance to read A Saint of Our Own: How the Quest for a Holy Hero Helped Catholics Become American, the 2019 book by Kathleen Sprows Cummings, Notre Dame history professor and former director of ND's Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism2. Awesome book, I loved it, the amount of research that went into it is staggering. Cummings clearly had to comb through centuries of reporting and church records and correspondence between clergy and laity in various pissing matches over who got to be a saint and how.

And there are a lot of those records, because the process by which a dead Catholic becomes canonized as a saint is many things, but certainly not “consistent” or “simple”. Prospective saints can have every single piece of their extant writing, including diaries or personal letters, combed through by church representatives to make sure they never wrote anything heterodox3; presumably, this standard also applies to any jigsaw puzzle designs. A team at the prospective saint’s local diocese has to make the case for their holiness and present any testimony they can from people who knew the saint personally; a different team has to shepherd the cause through the soul-numbing bureaucracy of the Vatican, and part of the reason that canonizations take so long or don’t always succeed is a failure of the two teams to properly coordinate or, in some cases, get along with each other, because every single one of these teams, invariably, includes some priest or monsignor with a hair-trigger temper and fragile ego.

But, most famously, you need to have a couple of miracles to your name in order to become a saint. And not only is a miracle hard enough to verify - you usually have to have a medical turnaround so incredible that a non-Catholic doctor has to testify to the Vatican that there is no possible scientific explanation for what happened - but you have to also conclusively attribute this technically impossible thing to the prospective saint and that person alone. If some other already-saint stepped in to help with the miracle, the prospective saint is screwed and doesn’t get to count the miracle as their own, because that miracle has the stink of a different holy person on it. Which, of course, leads to moments like this in Cummings’ book, discussing the cause for the canonization of Elizabeth Seton:

“Miracles, by definition, materialized in God’s own good time. Nevertheless, there was plenty that human advocates could do to provide a nudge.”

Already a fantastic start. Cummings continues:

“[Vincentian Priest] Salvator Burgio, in fact, had written a helpful primer on how Seton’s devotees could help generate the required miracle, including the advice that they should invoke Seton’s intercession as frequently as possible, particularly for dire medical cases, and pay attention to the timing between the invocation and the healing. Equally important was the need to invoke Seton exclusively. If at any point in the investigation it was revealed that a petitioner had invoked the intercession of more than one saint in requesting the miracle, the case could not move forward for approval. This was - and is - one of the points in the canonization process where institutional and personal perspectives seem especially detached from each other. For the beneficiary and his or her loved ones, a cure was a cure, and which saint received intercessional credit mattered little or not at all…Elements of a cure often evoked events or maladies in a saint’s life, and because two of Seton’s biological daughters had predeceased her, Seton’s sisters often received prayer requests for sick children.”

And yes, perhaps Seton’s street team had gone to parents of gravely sick children and encouraged them to pray for Seton’s intercession while also admonishing them that they weren’t going to get jack if they tried to loop in any other saint besides Seton, but rest assured that other local teams working on sainthood causes were showing even more hustle and also grind, like the people working to canonize the late Philadelphia bishop John Neumann:

“[Former Notre Dame president turned Philadelphia bishop John Francis] O’Hara also relied on his Holy Cross connections to generate devotion to Neumann and to advance his cause. In 1953, for example, he procured relics of the prospective saint for each member of the Notre Dame football team when they arrived in Philadelphia to play the U.S. Navy team.”

Look, sometimes a miracle is when your cancer disappears, and sometimes it’s when you go 17 for 25 with 175 yards in the air and one passing touchdown4. Look, O’Hara did this because he wanted to push Neumann’s cause and he wanted Neumann to be a saint. Part of the reason O’Hara wanted Neumann to be a saint was because Neumann was bishop of Philadelphia a century before O’Hara was, and O’Hara thought it would be cool if a guy who used to have his job became a literal saint. It would make the diocese of Philadelphia the most important diocese in the country because it was the only one to produce an American saint, and that would have made O’Hara seem like a pretty cool and important bishop.

This sort of thing happens all of the time in the book - people are hustling to finally get America its first saint, and maybe the reasons for some of them are a little less “they were moved by the Holy Spirit to champion the cause for sainthood” and something closer to “it gave them a chance to make themselves look good and also yell at other people”. Whatever your thoughts about the Holy Spirit, or the infallibility of canonization, or the people that God has chosen to spread the Gospel, you have to square up against this fact of sainthood: saints do not exist separately from a process that is administered, top to bottom and start to finish, by human beings. And that means that who becomes a saint and when all gets determined by a very large and fragmented group of people who are trying to establish different narratives and who are representing, let's say, a wide range of intellectual and administrative competence.

The idea of “narrative” is behind all of this: when someone becomes a saint, when they are literally made part of the canon, their story becomes part of the story of Catholicism in that era and that part of the world, a story that people can identify with and lean on in tough times. So the kind of stories you pick for the canon matter: what is the story of Catholics in America? It's not an easy question to answer.

It sounds weird now, but for the vast majority of Catholic history, the Vatican didn't give much of a shit about what went on with the church in America. We were tiny and fragmented, a remote outpost where the world could throw its Italians. Nobody important in the life of the church lived there, and the Vatican didn’t have to spend any time on the needs of American Catholics. What could change that? Well, what if there was an American saint? What if we had one of those holy heroes that all the European countries got? What if the story of American Catholics became part of the literal Catholic canon? That was a major goal of the canonization campaigns that American Catholics started to lead in the late nineteenth century, but it wasn’t the only goal. As Cummings writes:

“The absence of American names in the canon of saints left many U.S. Catholics feeling not only spiritually unmoored but also periodically subject to the condescension of their transatlantic counterparts…U.S. Catholics’ desire to search for a saint of their own did indeed spring from a desire to persuade the Vatican to recognize their holy heroes. But U.S. Catholic believers had another reason for touting homegrown holiness. To them, saints served as mediators not only between heaven and earth but also between the faith they professed and the American culture in which they lived…Seton and other U.S. saints were canonized not simply because they were holy people. They were canonized because a dedicated group in and subsequently beyond their inner circles wanted them to be remembered as holy people [emphasis sic].”

The idea of narrative goes two ways here: a narrative that American Catholics wanted to present to the Vatican about what kind of Catholicism Americans practiced, and a narrative that Catholics wanted to present to other Americans about what Catholics contributed to the country. Every American cause for sainthood was an exercise in pushing narratives in these two directions. But the actual narratives being pushed varied widely, because “the story of American Catholics” kept changing throughout our country’s history. American Catholics were missionaries like Isaac Jogues or Junipero Serra. But American Catholics were also indigenous converts, like Kateri Tekakwitha. But American Catholics were also part of close-knit immigrant communities, like Mother Cabrini. But American Catholics were also fighters for racial justice, like Katherine Drexel. But American Catholics were also educators and almsgivers like Elizabeth Seton. The nature of how America changed with different waves of immigration, and shifts in Catholicism's status and size in the America in the past 150 years, causing all sorts of stops and starts in canonization campaigns and a final Chex Mix of actual canonized Americans, none of whom work as a stand-in for the full story of American Catholicism. No single person really could, I think. And in recent decades, we’ve seen a very different sort of narrative start to get pushed with sainthood causes.

PART THREE

Pushing a narrative is a human action, not a divine one. We don’t just wake up and find out that the Holy Spirit has chosen a new saint; rather, people work on this - they do a lot of work - because they want to make a certain narrative a part of the official Catholic story, and a part of the official American story. For example, let’s take a currently open American cause for sainthood, and the narrative about Catholicism that this cause is trying to advance. Dorothy Day: she might be a saint someday, right? Her cause is progressing slowly but surely in the arch of New York and at the Vatican. What do we know Dorothy Day for, that would be the main part of the narrative about American Catholicism that we’re all trying to canonize? We’re both thinking the same thing, I’m sure. I’m sure we are. Everybody assumes that when we talk about Dorothy Day, we’re talking about the exact same set of Catholic values and things that Dorothy Day is known for. We don’t even have to say it out loud. But, you know what? Just to be sure, why don’t we both close our eyes, count to three, and then at the same time we’ll say the main thing everyone knows Dorothy Day for. Okay. One, two, three: she’s a mascot for militant anti-abortion activists.

Oh, is that not what you were thinking of? You were thinking about, like, the Catholic Worker stuff that she dedicated her life to and wrote multiple books about? No, no, Cummings lays it all out for us: when New York Cardinal John O’Connor opened Day's case for sainthood, he was very clear about why he wanted Day to be remembered as a saint:

“...the unwillingness to pursue formal canonization is also fueled by feminists’ belief that doing so would force the candidates into clergy-defined gender roles. Such fears are not unfounded, as attested to by the most controversial cause launched by New York’s Cardinal O’Connor: that of Dorothy Day. Day’s singular achievement was founding the Catholic Worker movement in 1933, and to many of her devotees and admirers, the case for her holiness rests on her fierce commitment to social justice. In announcing the opening of her cause for canonization. O’Connor, by contrast, foregrounded Day’s pre-conversion abortion, positing her as a model for women who had had or were considering abortions. ‘It is a well-known fact,’ the cardinal said, ‘that Dorothy Day procured an abortion before her conversion to the faith. She regretted it every day of her life.’ Day’s appropriation as a pro-life saint has outraged critics who claim that church leaders are attempting to tame Day’s message by recasting her in the familiar trope of the ‘fallen woman’ rather than grappling with the radical challenge that her life and example pose to the Catholic Church.”

Obviously, the church's narrative about Day has since shifted a little closer to “the thing that everyone actually knows about her”. But O’Connor was a very prominent anti-abortion voice in the church, and tried very hard throughout his career to influence and shape Catholic political engagement around the issue of abortion, so when he opens a cause for sainthood, even for a woman that everyone knows about for a completely different reason, abortion is going to come up.

Saints do not exist separately from a process that is administered, top to bottom and start to finish, by human beings, and that means that there may be room for cynicism and opportunism in the canonization process, especially as church politics became more polarized in recent decades. John Neumann’s relics ended up not delivering decisive miracles for the Notre Dame football team - ND still went 9-0-1 in 1953 with John Lattner winning the Heisman, but they couldn’t get a consensus national championship because the AP picked Maryland, so yeah, you don’t get a feast day off of that - but Neumann eventually got canonized in 1977 after the narrative around the precise nature of his holiness shifted. Neumann’s cause for canonization was originally built around the work he did to expand the Philadelphia parochial school system and provide a haven for the immigrant communities of his city, but in the late seventies, it became easier to brand him as a “pro-life” bishop, seek his intercession for dangerous pregnancies or deliveries, and use his canonization as proof that God, more than anything, cared about criminalizing abortion in the post-Roe United States. John Paul II was happy to support this narrative when he finalized Neumann’s canonization, and happy to advance the causes of other prospective saints, like Gianna Molla of Italy, who could support a narrative about the centrality of anti-abortion work to the church.

If we look at recent canonizations, one narrative that the Vatican - and our recent Popes - appear to be pushing is “look how great all the Popes are”. It feels like the fastest path to sainthood today is becoming the Pope first, much like the fastest path to winning an Oscar is playing the Joker in a movie, and I did make that same joke in an essay two years ago, but I’m repeating it here because I think it’s a very good joke5. Mollie Wilson O’Reilly, one of the only people working in Catholic media who is funnier than I am, wrote about this in Commonweal back in 2018, directly addressing Pope Francis:

“As you know, in 2014, a year after you became pope (and not even ten years after the death of John Paul II), you canonized Popes John XXIII and John Paul II on the very same day. And now I read in the paper that Paul VI is on the docket for 2018, and my first response is to joke, “Who’s next, St. John Paul I?” But it turns out I can’t make that joke, because you officially recognized John Paul I as “Venerable” just a few months ago. Is it possible you’re getting a little carried away? It’s not that I have anything against these men as individuals. Who am I to judge? It’s just that it seems like a pretty big coincidence for all of the popes since Pius XII—ahem, Venerable Pius XII—to have been men of uncommon heroic virtue. You must agree that, in theory, a non-saintly person could become pope. I will go so far as to say that it has happened before. So, if the modern church really has managed to elect an unbroken string of papal saints in the past century, well, that’s impressive, but considering that the pope is the one who gets to make that call, it’s also a bit...suspect.”

But the thing is, none of us had the full picture when O’Reilly wrote this in 2018, because it wasn’t until 2020 that we learned more about John Paul II and my wife asked me “so, does the Catholic church have any way to…un-saint someone?[They do not.]” Our guest speaker at the very beginning of my essay speculated that John Paul II would be remembered as the patron saint of sex, and I feel very comfortable betting against that outcome now. When the 2020 McCarrick report originally came out, I wrote this:

“When you look at the McCarrick report through the lens of my two favorite moral questions, "who has the power to change something?" and "did they?", the very clear answers are "so many people" and "no, they actively made things worse". Unfortunately, perhaps the one person with the most power to change something was Pope John Paul II, who was - for many, still is! - beloved by the Catholic church so much that he was fast-tracked to sainthood within a decade of his death. Schools and churches are named after the guy. In a bit of extremely cruel irony, he's the author of the bulk of the modern church's teachings on sexual morality. But in 2000, according to the report, he was informed of credible allegations of McCarrick's abuse and decided to promote him to archbishop of Washington DC anyways. A year later, he elevated McCarrick to cardinal. McCarrick went on to become perhaps the biggest source of shame for the American church in the past century. There aren't checks and balances on the Pope's power when it comes to deciding who gets to be a bishop. John Paul could have delayed McCarrick's appointment until he got more information. He could have asked followup questions, or gotten others at the Vatican to dig deeper. Other bishops who warned John Paul about McCarrick could have pushed harder or gone public with what they knew. And if John Paul had decided to do something after the fact, he could have easily pulled McCarrick out of his post whenever he wanted, even if he didn't go as far as Pope Francis eventually would in laicizing McCarrick. Why didn't John Paul II do any of those things? Was he an evil man? Was he secretly destroying Catholicism from the inside? The report speculates on his thinking, and while we won’t ever get a definitive answer fifteen years after John Paul’s death, we know that he was working with incomplete information because some bishops in the US covered for McCarrick, and we know that McCarrick defended himself to John Paul personally, and we know that, tragically, John Paul was just a guy who wanted to believe his friend.”

John Paul II got canonized in the Super Express Fast Track Less Than Ten Years After You Die Sainthood Lane because the Vatican wanted to promote the narrative that the people who lead our church are not Just Some Guys, they are unique and holy and saintly men handpicked by the Holy Spirit - God Himself - to lead us and we should trust and celebrate them. Rushing into that narrative - a narrative that I am tempted to see as very cynical and opportunistic - has blown up in the church’s face. It’s not the only time that a canonization narrative has come back to bite us.

During worldwide protests for racial justice in 2020, several California statues of Junipero Serra - the Spanish missionary canonized in 2015 after a decades-long campaign - were torn down or vandalized. Protestors believed that the Catholic church had canonized a brutal colonizer and had made paternal mistreatment of indigenous people a celebrated part of its official story. But, of course, if you listen to Salvatore Cordileone or Robert Barron or Jose Gomez, you know that the only reason people were mad at Serra in 2020 was because their minds had been poisoned by this new wave of evil anti-Catholic Critical Race Theory, that Serra had never done anything wrong, and that having any sort of opposition to the veneration of Serra was ridiculous. The only thing that could undercut these bishops' argument is if there were repeated instances, over the past several decades, of indigenous groups protesting the cause for Serra’s canonization, for exactly the same reasons that we all discussed in 2020, and if Cummings had documented that in her book and shown that Serra’s history had been a cause for concern for a very long time. So: who are you going to believe, “the bishops” or “someone who actually looked it up”?

“In the 1960s, Junipero Serra, the Spanish-born Franciscan whose cause formally opened after the North American Jesuits’ canonization, emerged as a particular flash point for native protests. Serra’s supporters insisted it was misguided to make Serra a scapegoat for the misdeeds of European colonizers and sought to counter negative publicity by framing him as a perfect saint for the modern age.”

Well, that was the sixties, when everyone was a filthy hippie. If we move to the nice neoconservative renaissance of the late 1980s:

“Native Americans themselves had begun to argue the opposite in the 1960s, accusing Serra of complicity in the extinction of native peoples and traditions. Writing [in 1988] at the time of beatification, Monsignor Paul Lenz, the executive director of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, dismissed such criticism as ‘nonsense’, arguing that it was unfair to hold Serra accountable for the sins of California’s Spanish colonizers. Lenz allowed that the Spanish had done ‘much damage to the daily living, health ,and culture of the California Indians.’ But the fact that Serra was Spanish, Lenz argued, should not make him automatically guilty. Lenz hoped the ‘exhaustive study’ undertaken to support Serra’s beatification would settle the matter.”

Guys, what do you think the immediate next sentence is?

“It did not. The year of the beatification [which, again, was 1988], native activists protested at Serra’s burial site in Carmel, and vandals defaced a statue of Serra at the San Diego mission, scrawling phrases such as ‘genocidal maniac’ and ‘enslaved Indians’ at its base…by 2000 the [Franciscan] congregation’s enthusiasm for actively pursuing the cause seemed to have wavered.”

Protests against Serra have existed since the start of his canonization campaign, because protestors did not like the narrative being advanced by that campaign, a narrative that elided the role of violent Spanish colonization in destroying the indigenous people of California, colonization in which Serra was absolutely a participant. The Catholics advancing the cause of Serra’s canonization thought that their narrative of Serra’s missionary work trumped the indigenous Americans’ narrative of brutal suffering and genocide, and ignoring those voices - or outright dismissing them, as multiple currently active bishops have done - has consequences for the church’s moral credibility.

Again, pushing a narrative is a human action, not a divine one. So as pockets of the church become more insular and echoey and isolated, sainthood is becoming less about recognizing the universal call to holiness and more about fights over narrative. As Cummings says towards the end of her book:

“No longer outward expressions of a deep yearning for holy heroes who sprang from their own time and place, favorite - or relentlessly “informal” - saints have become signifiers of where Catholic individuals and groups position themselves within the church, often on issues related to gender, sexuality, and social and racial justice. The search for a holy American hero had begun as an effort to define and articulate an American Catholic identity to outsiders to the faith and to the United States. It ended when canonization evolved into one of the most telling wedge issues, if not necessarily the most obvious, among U.S. Catholics…holy heroes have become far less meaningful than they once were, not only theologically but also culturally, as U.S. saint-seekers, influenced by papal initiatives, globalization, and the nation’s culture wars, have abandoned their pursuit of an American brand of holiness in favor of fragmented efforts to define what they envision as an authentically Catholic one.”

I do this all of the time. Maybe you do too. There are saints that I like, and those saints, for me, help me define what ‘being Catholic’ is, and they make me feel like I’m a good Catholic because I like the same things that my favorite saints like, and I can use the stuff they wrote or said to score points in my head when I see some other Catholic saying or doing something else that I don’t like. It is very stupid and childish, but it is real, and when I jokingly describe myself as a “Sicko Woke Liberation Pronoun Critical Race Oscar Romero Gender Marx Socialist Democrat Dorothy Day Mental Illness Left Pete Seeger Red Catholic”, you get the idea of what I think is important and what sources in the history of the church I like to lean on the most. If I described myself as a “Big Strong G.K. Chesterton Fulton Sheen School Voucher Council of Trent Mother Angelica Rosary Gun Hallow App Catholic”, you’d get the opposite idea. Both Catholic, with two different bookshelves, two different social media feeds, two different liturgical languages, two different clusters of saints that you like. These two different Catholics each feel like they’re the actual good Catholics, because there’s enough in the communion of saints and the broader attic of Catholicism that they can draw on. At their best, the saints can help us feel at home in a church where we sometimes feel out of place, but at their worst, the saints become inhuman tools, ammunition even, the way to prove that we’re the ones doing Catholicism the right way, because I can find the right quote or the right practice from this one guy, and hey, he’s a saint and you’re not, God picked him to be a saint, how are you gonna top that?

In 2017, author and former Catholic Worker Robert Ellsberg gave a talk at New York’s Sheen Center for Thought and Culture, which he adapted into an essay for America titled “Treating Saints Like Superheroes is a Dangerous Game”,

“Hagiography has become identified with a particularly saccharine, credulous and pious style of writing that conforms its subjects to a stereotypical mold—the proverbial “plaster saint.” Such saints, wrote Thomas Merton, are presumed to be “without humor, as they are without wonder, without feeling, and without interest in the common affairs of mankind.... They are always there kissing the leper’s sores at the very moment when the king and his noble attendants come around the corner and stop in their tracks, mute in admiration.”…In fact, as Merton would ultimately reflect, “For me to be a saint means to be myself.” If that is the goal of the Christian life, then I think we have much to learn from those who have walked this path. But first we have to take the saints down from their pedestals—to show them as flesh and blood human beings, who tried as best they could to live out the challenge of the Gospel in their particular moment in time.”

Maybe Ellsberg - or, really, Thomas Merton - has something here. There’s a way to read this, of course, where you can take away that “the saints were not perfect” (which we know) and “I’m not perfect” (which we definitely know) and that might lead you to “it’s okay that I’m not perfect”. Maybe the saints are not about a plaster person who was perfect all of the time, and instead they are about someone who makes me feel comfortable in my own imperfection, for to be a saint is to be myself. Maybe knowing that there are saints out there that make me feel at home in this idiot church is something, and knowing that others who believe very different things can also feel at home because of very different saints, and if we feel at home in the same place, if we can feel comfortable here in the same church, then maybe someday we can feel comfortable being at home with each other, different though we are, united through our love for the saints and their encouragement to be ourselves. That might be a nice place to land this essay.

But I can't stop thinking about Jay Reinke.

PART FOUR

Nonfics appears to be a Canadian blog about documentary films; when The Overnighters was playing the festival circuit in 2014, the blog scored interviews with both Reinke and the film's director, Jesse Moss, apparently because Reinke read the blogger's very positive review of the film and reached out through the comments section on the post.

Reinke can never work as a minister in the Missouri Synod Lutheran church again; a year after the film, he ended up in a low-level sales job hawking welding equipment. He was, after the film came out, still trying to make it work with his wife and kids. He was initially - and understandably - uncomfortable with the film coming out, but ultimately signed off on what was in there, toured the festival circuit with Moss, and considered The Overnighters a good, if necessarily incomplete, document of the two-year Overnighters program. But he was still worried about how people would see him after the movie came out:

"My fear is that if it ever plays in Williston or North Dakota it will be seen as “See, he did this all just for his own sake.” That’s my fear. I’m trying not to serve that fear, but it is a little hard. That’s my greatest reluctance, is that it would be seen as me, people would see it as evidence that my motives always were about serving myself. And that’s a little hard to take, but I’ll take it."

That was important to Moss, too. The reveal at the end of the film is a bombshell, to be sure, and the film wouldn't be the same without it, but Moss didn't think it took away from the film's tough questions about charity. If anything, the reveal made those questions even more pointed:

"He opened his life to me, and I felt like, not that I needed to make a film to make him happy, but that I needed to make a film that was honest and truthful and that he could believe in. That was really important to me, and when he had to make the decision to come to Sundance, I really wanted him to be there. I said, “Jay, I really want you to trust me, and I believe that when people see this film that they will be moved and inspired and provoked and they will see you compassionately, as you saw those men and in all your humanness. But I don’t know that for sure but I believe that will happen.” He trusted me and he made that journey with the consent of his wife. He did get affirmation and that was it would have been very hard for me to share this film without him because of how much he’s given me and how close we became. That was because of the nature of what happened. It was of course very hard for him and his family and how much attention this film brings to a difficult period in his life, the concern that it would overshadow the program or cast a light on the program that would make it hard to or obscure the deep profound message of his actions."

And it is a deep profound message. For ninety-five percent of the film, you're going "this is it. This is real. This is a living saint. This is what Christianity should be. I feel like I want to be a Christian based on what this man is doing." And then in the final minutes, you're mostly going "well, shit". The totality of Reinke’s life, the cloudy motivations, the spoiled narrative, all of those throw a wrench in your original plans of emulating Reinke’s selflessness. Maybe the saints are there to help us feel at home in the church and comfortable being who we are, except that we might not be very good at picking saints sometimes, and the saints themselves sure seem to let us down a lot of the time, whether they're the pastor in North Dakota or the Pope from Poland. So what do we do with the saints, then? I'm asking. I don't know the answer.

The early G.O.T.H.S. essays were about pretty easy targets; it didn't take a ton of deep research to show that someone like Michael Voris or Randall Terry was an idiot6. But occasionally I'd act like a pissy little iconoclast and dedicate an essay to critiquing someone that Catholics like me generally liked. John Paul the Second? More like John Paul the Suck-ond. Blase Cupich? More like Blase Suck-ich. Joseph Bernardin? More like Joseph Berna-suck, you get the idea. The point I was trying to make while writing these pieces was not “everyone is bad and you should never feel that anything will ever be good again”, the point was that even when you have someone who people generally like and who appear to say all of the right things, you still have to look at the material actions taken by people in power, because, more often than I'd like, the "good" people in power acted materially identical to the way the "bad" people in power would, meaning that the big problem might be less about who was good or bad and more about how power usually ended up getting used. I wanted to focus on sepcific decisions a person made or specific actions that person took, rather than the narrative of who that person “was” or what they “meant”.

I don't want to ruin the saints for anyone, least of all myself, I really don't. But the Catholics who became saints became saints when the people in power used their power, and any time people in power use their power, you should be watching with some level of skepticism. Many saints became saints for great reasons. But some of them became saints because certain people pushed a certain narrative at a certain time. And some of those saints did very bad things while they themselves were Catholics in positions of power, and saying that isn't so much "iconoclasm" as it is "referencing an easily available historical record".

What this all means is that I need to look at the saints differently than I have in the past. I assumed, until very recently, that if someone was a saint, they were stamped by the church, and by extension God, as "DEFINITELY GOOD FOREVER", and that made me feel good about myself if I believed the same things that Oscar Romero or Teresa of Avila or John XXIII believed, because I agreed with the saints and that made me the Cool And Good kind of Catholic who was Actually Better than the institutional church that kept pissing me off. And that is basically how the people in Cummings’ book, the teams who advanced sainthood causes, saw it as well; they hustled for American saints because they wanted the Vatican to stamp their guy, and by extension their country, as Definitely Good Forever. They wanted to show that the Cool And Good kinds of Catholics lived in this relatively new country, and that the church should take that country seriously because of the kinds of Catholics it could produce. But that's not what we’re supposed to get from the saints, we’re not supposed to get confirmation that we were already Cool And Good.

The process of canonization is sometimes bonkers, but nobody even gets started in that process unless they were someone who acted the right way at the right time, in a way that moved and inspired others. Even if they didn't do it all of the time. Even if they didn't do it most of the time. They did it right, once, then they died, then Catholics decided they were worth telling stories about, then other Catholics decided they were worth emulating, then other Catholics started to pray to them. There’s a step there before the narrative gets created, during the saint’s life, when they do the one right thing at the one right time, and maybe that specific act should be our focus more than the narrative around an entire life when we try to emulate the saints.

Jay Reinke did one right thing for two years. The people he helped were very often those that we'd consider "bad" people, and he helped them, because they were in front of him. He took the bad people in, and you admire him for it, and then the movie reveals that he might not be one of the "good" people himself, and the movie asks you "so are you going to take Reinke in now? Is he going to be part of your canon?" And that question is a tough one, because you thought it was originally about who was "good" and who was "bad", when it might actually be about who acted the right way at the right time, regardless of whether they were good or bad, and whether I want to let that person move me to act the right way at the right time someday.

That is a very complex question. Here is something less complex: there are suffering people in my world and they are not hard to find. Suffering and unwanted people will show up in front of me, they often do, because of where I live and where I go, and sometimes they ask me directly to help them, to give them something so they can ease their suffering temporarily. Sometimes I could act but I don't. And then, a few times, I have acted, I gave them what they asked for, and hopefully it eased their suffering a little bit. When I act that way, I'm thinking about people like Jay Reinke, about how moved I was when I saw his apparent selflessness, and about how I would like to be that selfless someday, and maybe I can practice right now. And I also think that I'm not a very good person because I don't do as much as Jay Reinke did, but Jay Reinke also didn't think he was a good person either, and he just acted when he could, and it mattered for a lot of people, so I need to act when I can too, because the “kind” of person I am or what my life story is don’t mean nearly as much to a suffering person as the action I’m going to choose to take right now.

And it’s not like there’s some other plaster saint who is going to step in and save the suffering person in front of me while I walk on by and say “sorry, man”. There's just me. There’s just us. Because the saints are just us. We were them, we picked them, and now, every once in a while, we can act like they acted, those few times when they got it right. Even a sinner like me can be inspired to act the right way at the right time. I don’t think “to be a saint is to be myself” properly captures all of that. So here’s one way to put it: perhaps the saints are just God’s way of - in the words of God’s favorite band - giving bad people good ideas.

Don’t think you’re off the hook Arkansas, I’ll get you in another essay.

Here's my disclosure: I have not yet met Prof. Cummings in person, but a mutual friend introduced us through email so we've traded notes a few times. She very generously offered to send me a copy of this book, and that offer fit with the overall impression she made in her emails of being a very lovely person. To return her kindness, I have refrained from subjecting her to Rosemont: A Novel of Rosemont.

I was once told that this is why professional theologians almost never become saints.

These were Sam Hartman’s stats in the 2023 game against Ohio State, but I haven’t had a chance yet to look up whether that was enough to win.

You know who else would think it was a very good joke? The Dang Joker, that’s who.

I mean, I did do a ton of deep research, but it wasn’t especially difficult.