Sohrab Ahmari, Downward Spiraler

How a man with a unique life story became exactly like everyone else

[a note on content: this piece contains some brief discussion of the Columbine shooting]

I feel like most normal people don't know about Sohrab Ahmari, the New York Post and Catholic Herald opinion columnist; these people likely lead joyful and successful lives. However, if you’re a certain type of extremely online Catholic, or pay any attention at all to the hissy fits that conservative op-ed columnists throw with regularity, you probably know about the meltdown that Ahmari had on Twitter in late 2019, where seeing an ad for a library “Drag Queen Story Hour” threw him into conniptions and led him to loudly announce “to hell with liberal order. Sometimes reactionary politics are the only salutary path.” You probably also know that his meltdown led to a public debate with National Review columnist David French, which was covered by roughly 200 different media outlets in the context of An Internal War In The Intellectual Conservative Movement, but the debate was really notable for two reasons: first, because Ahmari called for an abandonment of the ideals of liberal democracy and, essentially, the installation of a rigid Catholic theocracy in America, and second, because the debate was moderated by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat (center in the photo below), who was clearly making an effort to look increasingly miserable as the evening went on.

But if you are like me and on Sohrab Ahmari Operating Thetan Level Three, you have also made an effort to learn everything you can about who Ahmari was before the drag meltdown, to understand why the drag meltdown actually happened. I’m proud to say that I’ve arrived at an answer: unfortunately, the answer is just that Sohrab Ahmari is a profoundly boring person.

This was a bummer to find out. Of all of the people I’ve written about, Ahmari is closest to me in age - he was born in 1985 - and he has, without question, the most fascinating life story; I can’t imagine any future subjects coming close. He was the son of libertine professionals in post-revolution Iran, and his spiritual journey winds through Shia Islam, American Mormonism, Nietzsche’s nihilism, Sarte’s existentialism, Marx’s Communism, evangelical Christianity, and eventually Roman Catholicism. He has embedded himself with Middle Eastern refugees crossing over into Western Europe, edited a book of essays on democracy by dissidents from the Arab Spring, and taught children in one of the poorest cities on the southern border. He went through all of that and then concluded, after seeing a picture of one (1) drag queen, that democracy was a failure. It certainly seemed extreme to me.

But it turns out that Ahmari is not an extreme voice in the conservative movement, or even a particularly distinct one, and the real story here is not one man’s reaction to Drag Queen Story Hour, but a school of thought, pioneered by neoconservative Catholics for decades, in which Ahmari came up and made a name for himself. The ideas that Ahmari pushes were pushed decades earlier by his favorite clergy and writers. The people he was pushing them to at his debate don’t really disagree with him in any meaningful way, and it’s damn near impossible to tell them apart by their writing alone.

Ahmari actually summarizes his professional output very well himself, writing in the beginning of his memoir From Fire, By Water: My Journey to the Catholic Faith, “There was enjoyment in Iran and grandeur of a kind, to be sure. But when it wasn’t burning with ideological rage, it mainly offered mournful nostalgia. Those were its default modes, rage and nostalgia. I desired something more.” Ahmari has, so far, failed at this: he has basically defined his career with nothing but rage and nostalgia. But being consumed by rage and nostalgia, and calling for the end of American democracy, is not a biographical tragedy. It’s a job description for the average conservative opinion writer, and Ahmari chose the loudest way possible to say “I’m exactly like everyone else who does this job.”

CHAPTER ONE - MR. SELF-DESTRUCT

"There is a purpose plainly marked in the fact that we are born man and woman, and it was once understood that this purpose found its expression in marriage as a blending of nature and law. If marriage were entirely a matter of law, then the positive law could prescribe virtually anything as a marriage: Brothers then might marry sisters—or brothers; they might even marry their household pets. Or, they might marry more than one person."

- Hadley Arkes

Like we all do, Ahmari spent his adolescence and young adulthood trying on different personalities and interests, as he details in From Fire, By Water. While he spent his childhood in Tehran, his parents were relatively liberal, letting Ahmari ask questions about Islam and watch bootleg VHS tapes of western films. Eventually, Ahmari and his mother went through the green card interview process and were finally able to immigrate from a stifling theocracy to - ah shit - Utah, where Ahmari hoped to leverage his knowledge of American pop culture and become a cool kid right away. Unfortunately, the pop culture he was most passionate about was Pink Floyd and The X Files, so he did not shoot to the top of Utah's social scene. Instead, he pivoted in high school to what would be the only iteration of Cool Sohrab:

"Volatile emotions sloshed about inside me like an acidic mixture in an industrial vat. I poured out the pungent solution in daily conversation and into various poems, short stories, and many a novel abandoned on the first page. Typically, these early literary forays featured antiheroic protagonists, who wore upside-down crosses and engaged in ultraviolence...I cultivated a gloomy persona and dressed in black every day: black denim, black combat boots, black T-shirt, and black trench coat."

Hell yeah, this guy rules. The first-ever goth on G.O.T.H.S. stopped listening to Pink Floyd, started listening to his new favorite band Nine Inch Nails, and wrote wannabe transgressive stories in a Moleskine he actually titled SOHRAB’S JOURNAL OF THEMATIC SUMMARY AND ANALYSIS. He later made reference to "the goth subculture and its swamp of bad taste," which can't possibly be right coming from a guy who's listened to NIN’s masterpiece The Downward Spiral all the way through. Ultimately, though, this personality - further enhanced by his love for Nietzche at this age - was less an authentic expression of Ahmari's worldview and more a contrarian reaction to the cheerful Mormons he found himself surrounded by, and whose religion he found absurd and deserving of mockery. He clarifies in a footnote that today, he likes Mormons as people and admires their charitable works, but that “my opinion of Mormon theology has remained unchanged," which is a very polite ‘fuck you’ to an entire religion.

As Ahmari began his undergrad education, he changed again, from Cool Sohrab to Communist Sohrab. In another attempt to be contrarian in politically conservative Utah, he joined the Salt Lake chapter of the Marxist-Leninist organization Worker's Alliance. Meetings weren’t well attended, as you’d expect for a Marxist-Leninist group in Utah, but Ahmari put in his time selling newspapers and talking about vanguard parties with three other people. One of the most important lines in Ahmari's book comes from this part of his life:

"When I dabbled in Marxism, a decade after the end of the Cold War, the ideology had been utterly discredited. Contrary to Marx’ predictions, capitalism hadn’t pauperized workers in the advanced industrial countries. Instead, it had spawned middle classes across the West, people whose material prosperity disinclined them to revolution."

While this is objectively incorrect, it wouldn't be a completely insane thing to say in 2001, if you had very limited life experience. But Ahmari presumably still thought it was true enough to write in 2019, after extensive life experience that would have exposed him to the devastation wrought by capitalism. He had even experienced a downshift in class status himself, moving from a relatively comfortable life in Tehran to a trailer park in Utah. More importantly, he joined Teach For America out of school and moved to Brownsville, on the southern border of Texas. For two years, his job was to spend all day with the children of a largely impoverished immigrant community - some of the most exploited workers in the country, encountered in the context of immigration, public education, commodification of housing, and countless other political issues - and he still believes that Marx was wrong because American capitalism never hurt anybody. This is incredible to me, even more so than hearing Trent Reznor's original version of "Hurt" and concluding that Nine Inch Nails is somehow not good. Encountering the marginalized, in my estimation, is a more effective way to change a person's mind than something like debating on a stage or reading an op-ed column, but Ahmari completely blanks here (there's probably also a critique of Teach For America in here, but it deserves a separate essay and a smarter author).

Moreover, it's not the only instance of Ahmari getting a once-in-a-lifetime experience with the poorest people in the world and just missing the lesson completely. He dedicates a chapter of his book to his trip to Istanbul for the Wall Street Journal, in which he embedded himself with a group of Middle Eastern refugees working to get smuggled into Western Europe. He notes at the beginning of the chapter:

"I was about to tell the story of the European migrant crisis from the inside, as no Western reporter had or could. Unlike most of my journalistic rivals, I spoke Persian, the second language of the migrant trail (after Arabic), and I could fit in with these poor souls. A career-defining triumph was at hand. I pictured myself signing a lavish book deal and, later, delivering an acceptance speech at some journalism awards ceremony."

Usually, a setup like this would hint at some sort of coming realization that there is more to the world than the author originally thought. Ahmari's account of his trip is harrowing - the refugees live in squalor, sudden acts of violence are a normal part of the day-to-day, and at one point a pimp tries to sell trafficked teenage girls to Ahmari and his contact. From all of this, here's what he takes away:

"My time in Ehsan’s safe house shattered what was left of my faith in perfectibility and progress and the bland secular universalism that is the lingua franca of Western elites...There was only one escape hatch that led out of the infernal prison in which my soul was trapped...I, too, had to throw myself at the foot of the Cross without delay."

Ahmari moves from only thinking about himself to only thinking about himself, but spiritually. He leaves Istanbul (he had to abandon the project to take care of his sick mother) without any recorded thoughts on the interlocking wars, climate crisis, and rise in nationalism that contribute to the migrant crisis. He somehow lands on the same critique of secularism that any other opinion writer can crank out in an hour. This is astounding to me, even more so than, I don't know, hearing Trent Reznor's original version of "Hurt" and concluding that Nine Inch Nails is somehow not good. This is also ultimately what leads to his conversion to Catholicism, which will also be disappointing.

CHAPTER TWO - HERESY

"Unfortunately for us, however, events in America may have reached the point where the only political action believers can take is some kind of direct, extra-political confrontation of the judicially controlled regime. Following the logic in Romer, the Supreme Court can in time strike down state statutes barring polygamy, sodomy, and incest."

- Charles W. Colson

Ahmari’s first experience at a Catholic mass comes about two-thirds of the way through his book, when, feeling unmoored by his excesses in young adulthood and all-consuming career, he stopped inside a Capuchin monastery in Manhattan on a whim. He was, by his account, overwhelmed by the beauty of the mass, and moved to tears during the transubstantiation. On his way out of the church, he spotted a photo in the vestibule of then-Pope Benedict XVI preaching in St. Peter’s Square, which moved him to tears again and brings us to the funniest passage Ahmari has ever written:

“Once more, I was choking back sobs and struggling to catch my breath.

The friar, who had witnessed all this, came up to me and asked if I was OK. I mumbled something incoherent.

‘That’s the pope, you see,’ the friar said.”

It is my dream, one day, to attend mass at the Vatican with Ahmari, and every time the Pope stands up, to jab Ahmari in the ribs with my elbow and loudly say “that’s him. That’s the Pope. Right there. Pope.”

Ahmari was attracted to the endurance and the ritual of the Catholic church, which makes sense given the preceding years of his life, and also makes sense because they’re two of the only good things left in the church right now. But he was also attracted to the authority of the church hierarchy, writing that “Pope Benedict XVI stood for the principle of continuous, even absolute, authority...I longed for stable authority as well as redemption.” After moving to London in 2014 for the Journal, Ahmari befriended Christian activists in the course of his work, and eventually started attending evangelical Protestant services with those friends. The previous years had led him to a sort of informal Christianity, and he was regularly reading theologians like C.S. Lewis and Benedict XVI, as well as the Bible; he describes reading the Gospel of Matthew in one sitting, but being underwhelmed by the whole thing until he reached the Passion narrative in chapter 26. This suggests that he blew right past chapter 25, which included a vision of the final judgment in which Jesus emphasizes the importance of the corporal works of mercy (feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and the like) in entering the Kingdom of Heaven. It’s a shame, but I suppose once you get a job working for the Wall Street Journal, you have to forget you ever read stuff like that.

Ahmari was still trying to figure out his identity relative to a church tradition, and found evangelical worship somewhat lacking. After stumbling across a high Latin mass in London, he was moved again by Catholic ritual:

“I savored the Mass of the Faithful, and when the people lined up at the altar rail to receive the Blessed Sacrament, I positively envied them. It was nearly unbearable to recall that I had spent a third or more of a lifetime worshipping idols - the idol of “history”, the idol of “progress”, and above all the idol of self - when the true God was this gentle, this self-giving.”

As we come closer to 2019, Ahmari’s understanding of the church’s role in the world will become less self-giving and more dominating. He returned to the church the following week and asked a priest to begin instructing him in the faith so he could join the church. Ahmari’s mentor priest in London was an admirer of Monsignor Alfred Gilbey, the late Catholic chaplain at Cambridge University, and author of We Believe, a commentary on the Catechism. So, in addition to the RCIA basics, Ahmari got educated in some of this Gilbey’s theological writing, and I’m sure Gilbey didn’t have any unsettling authoritarian views or anything that I would generally consider worrying. I’ll just take a look at Gilbey’s 1998 obituary in The Independent:

“He was a passionate lover of the "old" Catholic idea of monarchy and its personification in the person and ideals of James II....his distaste for all that was associated with the slogan "Liberty, Equality and Fraternity" was unbounded...The rot, according to this school of thought, had started with the French Revolution. Thus, not only was "liberalism" condemned but so were "religious freedom" and individual rights of conscience as then understood, that is, as implying the possibility of any legitimate opposition to Rome's monopoly of the truth.”

Oh. Well, it’s possible Ahmari didn’t know anything about that part of Gilbey’s personality, or that Gilbey fought tooth and nail to keep the chaplaincy at Cambridge from admitting women (he lost in 1956), or that Gilbey withdrew from publicly administering the sacraments after Vatican II basically out of spite, or that Gilbey generally was not a fan of democracy. That said, Ahmari references all of those things in his own book with wide-eyed admiration, laughing that “every few years the Spectator would dispatch a scribe to profile the cleric seemingly teleported to our age from Victorian times. Gilbey played the part with aplomb: “I don’t believe one man one vote is a sort of moral law!” “There you go again with this absurd idea that Christianity says all men are equal. It says nothing of the sort!”” Ahmari was drawn to the church in part because of its idea of authority, he would eventually value that idea of absolute authority above all else, and he had exposure, early in his Catholic formation, to someone who loved that authority even more than he did.

After this somewhat horrifying course of catechism, Ahmari eventually received the sacraments of initiation. Here's his mentor priest talking him through it:

"‘When that water is poured,’ he said at our last meeting before the big day, ‘you become truly initiated into the life of Christ—into Trinitarian life. Say to yourself, ‘I live no longer as I but Christ lives in me.’

‘And afterward?’ I asked.

‘The best thing I can do for you after I baptize you is to shoot you.’”

This is, to use the theological term, bad. In fairness to the priest, it's possible (and maybe likely) he meant this comment as an extremely dry joke, but Ahmari makes clear in subsequent paragraphs that he takes it at face value that the objective of Catholicism is to die at exactly the right time. This is treating Catholicism as a death cult, where you need to get to heaven as efficiently as possible, and nothing else matters. You can ignore the rest of the Body of Christ on Earth, you can live without compassion or the virtues of faith, hope, and love, all you need to do is die immediately after your sins are absolved.

With this thinking, there's no real need for the church that Christ instituted, as described in Acts, to go out to all nations, preach the Gospel, forgive the sinner, and heal the sick. Christ's new commandment to love one another, in John's Gospel, doesn't matter. The final judgement depicted in Matthew 25, which Ahmri shot through in his first reading, is unimportant. The legacy of practically every saint is nothing more than a waste of time. I'm starting to think Ahmari perhaps does not have the healthiest grasp on his faith. But if you look at this through the lens of Ahmari's true religion being the Catholic neoconservative tradition, then it makes a lot more sense, since that’s basically a death cult anyways.

CHAPTER THREE - MARCH OF THE PIGS

"The opinion closed with the preposterous assertion that “Amendment 2 classifies homosexuals not to further a proper legislative end but to make them unequal to everyone else.” To the contrary, any constitutional provision does what Amendment 2 did—it removes from some groups the capacity to alter the law except at the state or federal level. If one took the majority’s assertions seriously, as Scalia’s dissent noted, state constitutional provisions prohibiting polygamy would violate the equal protection principle."

- Robert Bork

Let’s take another look at that 2019 debate photo, the one where Ross Douthat looks like he’s questioning every decision he made that brought him to this point in his career:

Just kidding, that’s a different photo from the same event, there’s like eight of them and they’re all equally funny. But in addition to Ahmari (left), we should also take a second and talk about the other two men in the photo, as they are in the same line of work. David French is the man on the right-hand side of the photo, and at the time, he wrote for the National Review; this entire debate was prompted because Ahmari, in his original tirade, accused David French, by name, of being too squishy and polite to pursue the hard reactionary policies that would be needed to purge the world of Drag Queen Story Hour.

National Review, of course, is the magazine founded in the 1950s by round wet Catholic William F. Buckley, Jr. Buckley was a devout lover of traditional Catholicism; he wrote multiple books on his religion on how it influenced his political viewpoint, and the Review had a dedicated religion vertical with its own editor. We’ll talk about that editor in a little bit.

Buckley’s goal in founding the Review was to give the growing American conservative movement serious intellectual cred; the intellectual cred, in the early days of the magazine, was used to argue against school integration and for the rights of whites to run the government even in jurisdictions where they were a minority, as the magazine called them “the advanced race” compared to black Americans. Sadly, there is no succinct political term I can use to describe the ideology of a magazine that considers whiteness to be supreme among the races in our country, but if there were, I would say that the National Review started as a proponent of that ideology and in many ways today, still advocates for minority rule in service of that ideology. I suppose I should mention that Buckley did try to drum the John Birch Society and antisemites out of the American right, but also the Review in 2017 criticized the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture for not focusing enough on black-on-black crime, so you tell me how much things have changed:

This is the magazine that employed David French (he’s moved to another publication since the debate); French, in many ways, embodies the kind of conservative that the National Review is written for: erudite, polite, Christian, thoughtful, law degree, the kind of guy that you’d consider a policy wonk more than a red-meat blogger or politician. He was horrified that the Republican party would nominate someone like Donald Trump as a presidential candidate - in fact, the whole Review was, having dedicated an entire issue to “Against Trump” arguments during the 2016 primary. French actually considered running for president as an independent conservative candidate in 2016, and even wrote about it in the Review, conceding that he didn’t have the name recognition or money to really mount a challenge to Trump and Clinton, but encouraging others to consider it, for the good of the country. That independent conservative candidate ended up being former CIA operative Evan McMullin, to whom the Review dedicated multiple articles, in which writers fantasized about him getting enough electoral votes to throw the election to Congress, who would of course vote him into office over Trump (in retrospect, lol).

The “Against Trump” issue didn’t have any impact on the primary elections, and McMullin couldn’t mount a serious presidential campaign for respectful and thoughtful conservatives, because nobody gives a shit about respectful and thoughtful conservatives. There are thirty-six of them, total, in the country: twelve of them write for the Review, and the remaining twenty-four are actually fictional characters created by Aaron Sorkin across multiple television series. Whatever intellectual conservative movement Buckley tried to solidify was upended by in 2016 a senile game show host who half-understood that voters just wanted to dominate their perceived enemies, and the conservative movement was decaying long before that.

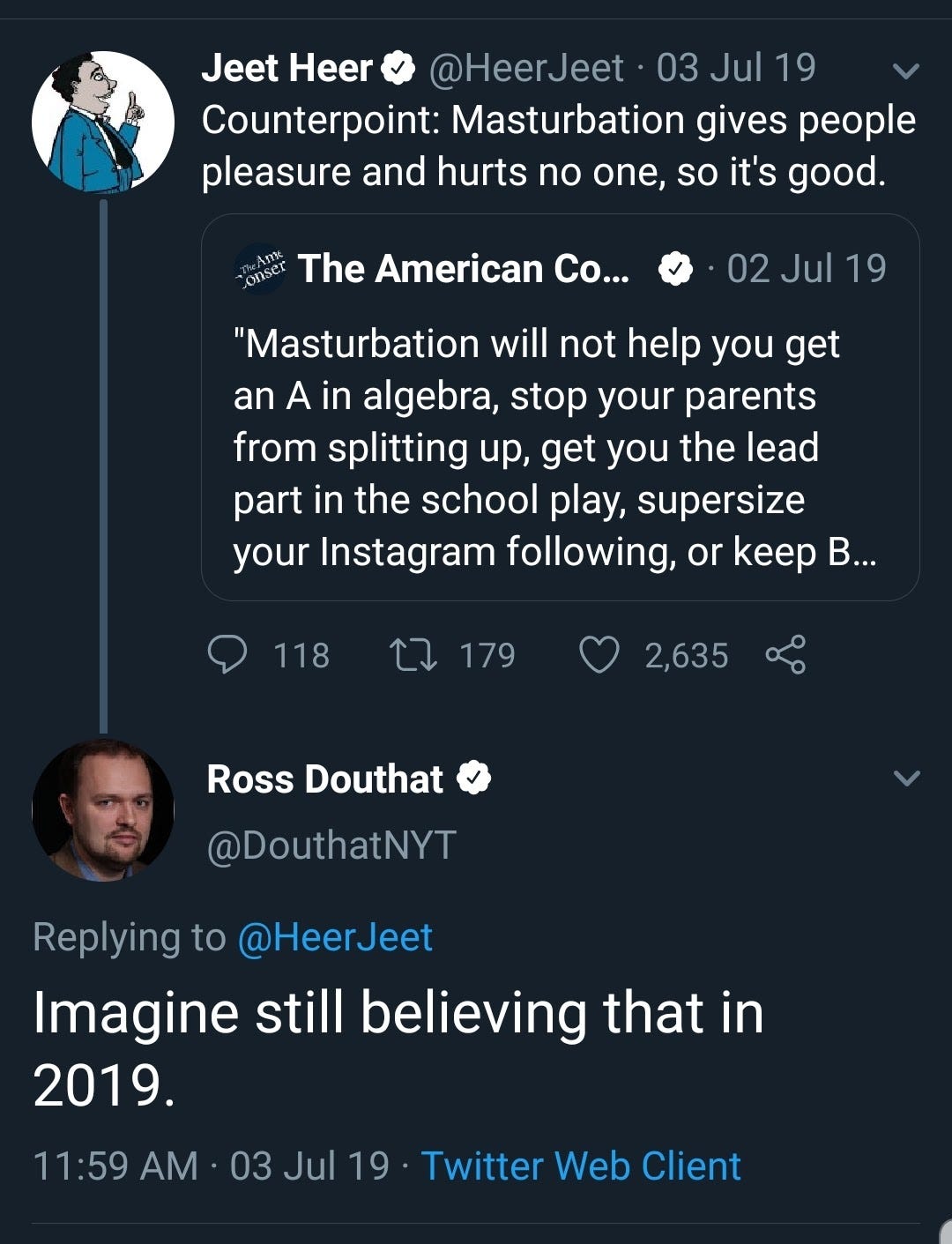

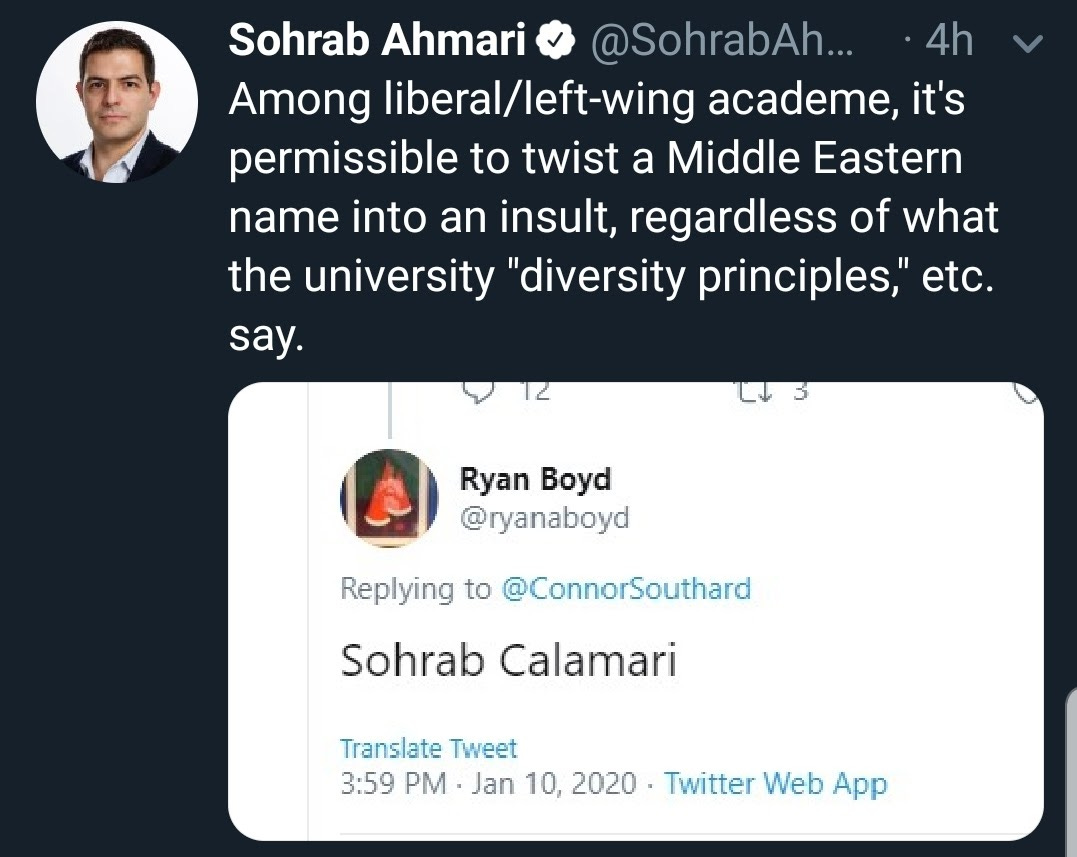

Ross Douthat is the man in the center of the photo moderating the debate, and he writes regular columns for the New York Times, although he was also a protege of Buckley and has contributed to the Review in the past. Like Ahmari, he is an adult convert to Catholicism, and he believes that a restoration of Catholic values is critical to America finding its way back to goodness and stability in this increasingly chaotic and brutal political era. He once wrote a book on how Christianity, as a civic institution in America, descended into hypocrisy over the past few decades, through warped interpretations of the religion like the prosperity gospel; of course, he also wrote a different book on how Pope Francis is on the path to permanently destroying Catholicism, so it hasn’t all been home runs. He also appears to be terrified of sex, to the point where I’m pretty sure he’s avoided jacking off for the last four decades, and in one ominous tweet from last year he seemed to reference some sort of tragic masturbation accident that he never fully explained:

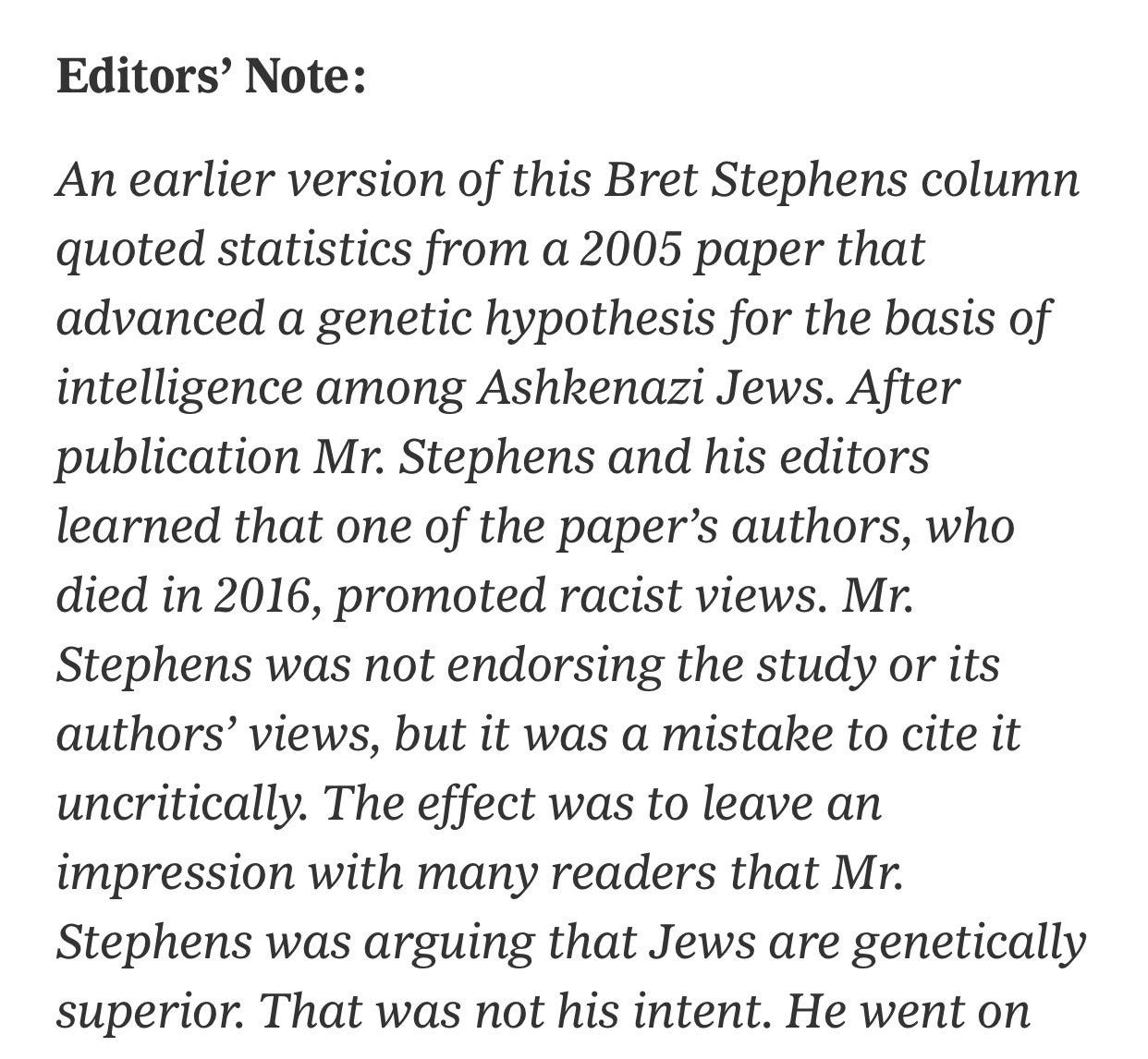

Amazingly, Douthat is actually in the top quartile of talent for op-ed writers at the Times, which, after the election of Donald Trump, made a big effort to hire more conservative voices to provide more so-called “ideological diversity” and get the paper’s generally liberal readership out of their “bubble”. Douthat’s working for the paper predates this whole philosophy, but the conservative voices hired under this new outlook from the paper have been pretty much uniformly awful. Quinn Norton was picked up and almost immediately fired by the paper because it turned out she spent her spare time hanging out with Nazis. Bari Weiss claimed that totalitarians were taking over college campuses, and cited a fake Twitter account as her only source; the paper eventually shipped her off to Australia in an apparent effort to shield American readers from her terrible brain. Erik Prince of Blackwater got to warmonger in a guest column that could have been Sponsored Content. And then, in a class all by himself, there is Pulitzer laureate Bret Stephens, who somehow finds new ways to be the most mocked writer in America every week; at the time of this writing, his most recent column had led to this incredible addendum from the Times editors:

Those were recent “diversity” hires, but there are also the long-time columnists like David Brooks, who cheated on his wife with an employee half his age while writing a book literally titled The Road to Character, or Maureen Dowd, a 68-year old woman who once freaked out after eating a pot brownie and infamously wrote her own version of Reefer Madness for the opinion pages. There is no meaningful daylight between the points of view of any of these columnists. They all think Trump is uncouth, free markets are good, socialism is Venezuela, and the biggest threats to American freedom are college students using preferred pronouns or black people disrespecting police or socialists being mean on Twitter. I'm far from the first person to raise this criticism of the paper, and Splinter (RIP) put it better than I could back in 2017:

“The Times’ bullpen of 14 regular columnists includes two white men named David, three women, and no women of color. Taken together, their output stretches from the tired orthodoxy of Clintonian Democrats to never-Trump conservatism. The idea that there is a genuine clash of ideas among these middle-aged writers is bizarre, and it harkens back to a political center that no longer exists—if it ever did.”

Since 2017, the Times appears to have made some more left-leaning hires, but Douthat continues to write with colleagues and for an audience that is overwhelmingly white, well-off, and center-right politically. The he clearly didn’t want to be at the Ahmari-French debate is maybe the single biggest positive testament to his character in years. All of this is to say that all three of the men in that debate photo - wait, here’s another one!

All three of those men work the same job, and it’s a job with no practical use anymore. You just write out your rage and nostalgia - the Review is nostalgic for the segregated 1950s, and the Times is nostalgic for something more like 1993 - and you just say the same stupid things over and over, without reporting, without any real research, without any consequences besides people goofing on you on Twitter. Are these three men meaningfully different from each other in their choices of topics or takes? It’s hard to say for sure, but here's one column from each of them from roughly the same time, see if you can tell who is who:

“The Covington Scissor: Welcome to Another Controversy Algorithmically Designed To Tear America Apart"

“Covington Catholic is the Terrible Sequel to the Kavanaugh Case"

“Dear Covington Boys: Everyone Failed You.”

Ok fine, but that’s one data point, surely that doesn’t happen all the time-

“No, Brett Kavanuagh Has Not Been ‘Credibly Accused’”

“Courtesy Is the First Casualty of Brett Kavanaugh's Confirmation”

“The Burden of Proof for Kavanaugh”

Ok fine, but what if I pulled one column from each of them from three completely different times-

“Porn isn’t free speech - on the web or anywhere”

“Let’s Ban Porn”

“Pornography Destroys American Morals and Culture”

So three men, with almost identical ways of viewing the world, and almost identical jobs in which they could express those views, and almost identical audiences, met in late 2019 to debate their, uh, significant differences. “All right,” you might say, “but Ahmari, in his call for ending American democracy, was at least saying something uniquely extreme and radical, right? When he wrote that piece about Drag Queen Story Hour and the end of democracy, the publication that ran it, First Things, wouldn’t have ever published anything like that before, right? They certainly wouldn't have published an entire issue in 1996 literally titled ‘The End of Democracy’ that asked the same questions and ended up causing a huge internal fight at the publication where multiple editors ended up resigning, right?” Have I got news for you.

CHAPTER FOUR - I DO NOT WANT THIS

"If marriage is detached from that “natural teleology of the body,” on what ground of principle could the law rule out the people who profess that their own love is not confined to a coupling of two, but woven together in a larger ensemble of three or four? When this question was posed in the hearings on the Defense of Marriage Act, it produced, among the defenders of gay marriage, a show of bafflement. Yet, the people who were inclined to dismiss the matter of polygamy were treating with a certain nonchalance something that deserved to be treated with far more caution and sobriety."

- Hadley Arkes

First Things was founded in 1990 as a Serious Intellectual Journal published by the archconservative Catholics at the Institute for Religion and Public Life. The founder, Father Richard Neuhaus, was the former religion editor of the National Review, giving him an impeccable conservative pedigree. He was also an adviser to George W. Bush on pro-life issues, co-author of a book on how Catholics and evangelical Protestants can better work together in the political sphere, a vocal advocate for denying Communion to Democratic candidates for office, and was once named one of the “Top 25 Evangelicals in America” by Time, which is pretty impressive considering that some of the other people of the list don’t think Catholics count as evangelicals, or Christians. He was a close personal friend of William Buckley, remembering him in First Things as a prime lay exemplar of the Catholic faith, and also had a chance to meet with weird monarchist priest Alfred Gilbey during Gilbey's only visit to the states, and write about it for First Things. So I think you’re getting an idea of where Neuhaus stands politically, and while contributors to the magazine today represent several different faith traditions, the majority of the editors have been Catholic and have very much been in Neuhaus' mold. The journal’s mission is to push back against secularism in the public square and fight for, among other things, “a democratic, constitutionally ordered form of government supported by a religiously and morally serious culture.” Within six years they had given up on that idea.

“The End of Democracy?” was a landmark 1996 “symposium” featuring multiple authors, writing at length, in responses to recent Supreme Court decisions, most notably Casey v. Planned Parenthood - which conservatives thought was going to overturn Roe, and didn’t - and Romer v. Evans - which struck down a Colorado state constitutional amendment that allowed for discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The journal’s editors laid out the thesis of “The End of Democracy?” as such:

“The proposition examined in the following articles is this: The government of the United States of America no longer governs by the consent of the governed. With respect to the American people, the judiciary has in effect declared that the most important questions about how we ought to order our life together are outside the purview of “things of their knowledge.” Not that judges necessarily claim greater knowledge; they simply claim, and exercise, the power to decide. The citizens of this democratic republic are deemed to lack the competence for self-government. The Supreme Court itself—notably in the Casey decision of 1992 - has raised the alarm about the legitimacy of law in the present regime...Some of our authors examine possible responses to laws that cannot be obeyed by conscientious citizens—ranging from noncompliance to resistance to civil disobedience to morally justified revolution."

What follows are long articles from luminaries of the conservative movement claiming Catholics should start seriously considering revolution, and while my original intention was to summarize and make fun of each of these pieces, I can’t do that because they’re all basically making identical arguments. The majority of the articles repeat, multiple times each, that if the Supreme Court can decide that “homosexuals” are supposed to be shielded from discrimination, they can also rule to make polygamy legal. The first four chapter epigraphs in this piece, all making that argument, are from the same 1996 issue of First Things! They’re not even on separate pages on the journal’s website! The best and brightest of Catholic conservatism united in 1996 to say "OK, but, uh, what if it's a slippery slope?"

You can probably guess how the rest of the pieces unfold: judges are unelected and uniformly amoral judicial activists - except Scalia, they love him of course - the Supreme Court has made abortion the law of the land, the American experiment has been a failure for any moral person for this reason and definitely not because of anything that happened in American history before 1996.

“The End of Democracy?” was a shitshow for years, and made it extremely easy for critics of the journal to paint it as a home for wannabe theocrats instead of conservative academics. At least three editors at First Things resigned explicitly in response to the symposium, presumably embarrassed that they had signed up to edit a thoughtful journal on democracy and instead fell into something much darker. Other editors tried to squeeze a book deal out of it, other religious magazines had “counter-symposiums” to the first symposium, and First Things was still writing about what a headache it was years later; in 1999, a writer at the magazine conceded that “although the editors anticipated charges of irresponsibility, provocation, and alarmism...they were clearly unprepared for the hurricane of criticism that followed. Rubbing salt in the wound is that many of the critics had been close allies.”

By the way, there is absolutely a case to be made for rethinking a federal judiciary that runs on lifetime appointments and doesn’t have meaningful checks on its own power. To make the case solely because you wanted some decisions to break more to the right is an extremely bad-faith argument. The 1999 First Things piece also conceded that “our efforts to teach what the Constitution meant to the Framers will inevitably seem partisan. In a sense they are. We do have different commitments than the usurpers do, not only as to procedure, but also as to substance. We are no more “neutral” than they are; we are only more objective,” a statement that threads the needle of meaning nothing, but still being wrong. One of the “objective” participants in the symposium was Robert Bork, who spent paragraphs lamenting that the justices were not conservative enough, and is the most well-known person who was nominated to the Supreme Court and couldn’t get on the Supreme Court because he was too conservative for the Senate. I’m not sure why First Things thought that Bork could provide an objective opinion on the justices, including the justice that got put in his seat instead of him (Anthony Kennedy). I did check, and First Things never had Bork write on the topic of “firing special prosecutors”, so I guess there is a floor to their subjectivity.

More importantly, First Things ran "The End of Democracy?" in 1996, the year in which, according to these writers, the Supreme Court finally went too far in countermanding the will of the American people. Here's what hadn't happened yet in 1996: the Court hadn't voted 5-4 to halt a recount in Florida and hand the presidency to George W. Bush, while the majority of voters had cast ballots against him. I'm sure First Things was apoplectic with rage at this decision, let me just check and see what they wrote at the time:

"All in all, it seems reasonable to conclude that the decision in Bush v. Gore, while unusual, was far from indefensible. The Court faced an extraordinary and unprecedented situation. It knew that the Florida court had perpetrated outrageous constitutional mischief, and by acting as promptly and authoritatively as it did it minimized the effect of that mischief. The majority Justices, confronted with a political and legal mess for which there was no unmessy solution, found perhaps the least messy solution available. Not every active use of the Supreme Court’s authority constitutes an exercise in judicial activism."

Huh, a surprisingly chill response to the unelected judges picking a president. I’m sure First Things would have been equally chill with the court ruling for Gore. But you know which Court decision probably made the magazine furious? Citizens United v. FEC, a profoundly anti-democratic 5-4 decision that allowed for unlimited campaign contributions from corporations and super-PACs, fundamentally undermining an individual citizen's free speech powers, as well as the idea of one-man-one-vote. Let's see how First Things took another bold stand in the name of the "consent of the governed":

"While some critics of the decision point to the problem of corporations influencing elections, it is very easy to miss, whether intentionally or not, that quashing free speech always amounts to nothing less than quashing free speech. Corporations are owned by people, just as unions are owned by people, and churches (and all other free associations) are composed of people in free association. This ruling is historically democratic."

Ok, well maybe the staff had turned over since 1996. But surely a magazine committed to the ideals of American democracy, through the lens of Catholicism, would find something to criticize about the 5-4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which gutted the Voting Rights Act in 2013 and opened the door for restrictive voting regulation in Republican-controlled states across the country? A decision which, as we've seen in the years since, has basically led to the resurrection of Jim Crow-era voter suppression in states like Georgia? Actually, First Things did find something to criticize: they thought that Roberts' majority opinion didn't cite specific enough parts of the Constitution. They also wrote this:

"The left greeted this decision as the second coming of Bull Connor, even though it leaves in place all the act’s substantive protections for voting. In reality, the decision, written by Roberts and joined by Kennedy, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito, was modest in scope...In a world where minority voting turnout is higher in Mississippi than in Massachusetts, the old 1965 formula no longer makes sense. All this may sound like common sense to those who see the changes in American racial attitudes since 1965."

You probably guessed this going in, but First Things was never really interested in restoring "consent of the governed", or really any sense of democratic pluralism. In fact, they have no problem with the federal courts (or anyone) subverting the consent of the governed, as long as the courts are doing the shit they want and not the shit the other guys want. This isn't complicated. It's how power works for most people, and the tradition of Gilbey, Buckley, and Neuhaus, all the way up through Ahmari, has always been about advocating against actual democracy and for something closer to theocracy. One person who understood power differently was the man who founded Catholicism, but these writers don't see how that would be relevant here. The New Republic put it better, writing that “even before Ahmari slimed French in its pages, it was perhaps the only magazine in American that provided a home for proponents of a religious state”.

What this ultimately means is that when Ahmari came out swinging against Drag Queen Story Hour, first on Twitter and then in First Things and then in a debate with David French, not only was he crapping out a disingenuous argument for abandoning democracy in America, it wasn't even a new disingenuous argument for abandoning democracy in America. The publication that ran his piece examined the same issue at length twenty-three years earlier; hell, when they did it, it was at least in response to a Supreme Court term and not an ad for an event at a public library thousands of miles from where Ahmari actually lives. Ahmari's advocacy for reactionary politics doesn't come from his experience as an Iranian immigrant, it doesn't come from his faith journey, it doesn't come from the work he did as a teacher or a journalist. His viewpoint is his viewpoint because that's what his job is as a neocon opinion writer; dozens have done the same job before him, and more will do the job after he retires, and none of them will be meaningfully different than him or Douthat or French. The man with a unique life story has become just like everyone else; let's see where that story ends.

CHAPTER FIVE - HURT (ALBUM VERSION)

"We’ve got dumber, more tribalised; we’ve found niches of other people that focus on extremity. For the miracle of everyone sharing ideas, I see a hell of a lot more racism. It doesn’t feel like we’ve advanced. I think you’re seeing the fall of the empire of America in real time, before your eyes; the internet has eroded the fabric of decency in our civilisation."

- Trent Reznor

Ahmari's actual 2019 piece in First Things, "Against David French-ism", is the product of a man somehow both in a tremendous hurry and with way too much spare time. That it got any attention at all is incredibly stupid, and was really only due to Ahmari's mentioning David French by name as an example of a conservative who respects democracy too much to get things done. The piece itself isn't even worth quoting, as it's full of specious arguments and terrible examples - Chris Pratt is a victim of cancel culture for being Christian! - and uses the Latin phrase mutatis mutandis, which nobody has ever actually had to use to make a rhetorical point.

The debate, at Catholic University in DC, was equally dumb. As we've established, Ahmari didn't say anything new when he advocated that we should abandon democratic order and enforce a societal structure that better fit his understanding of Catholic orthodoxy. David French obviously didn't say anything new, because the National Review hasn't said anything new since Brown v. Board. Ross Douthat didn't say anything new because he was busy quietly hoping God would strike all three of them down on stage. The only really funny thing that happened during the debate was when Ahmari got in a pretty good own on French; after French cited his own military experience, Ahmari countered, correctly, that French was in JAG and never saw combat. Respect.

It's truly remarkable, then, how much media coverage this event got. Every conservative opinion outlet wrote about it for weeks afterwards, because it was an internal fight within the conservative intellectual movement and everyone had to pick a side; it was the equivalent, on the left, of some socialist writing a 6,000-word post on Medium titled like “DSA Is At A Crossroads” as a way to explain why it’s okay that he said a racial slur in a branch meeting. Every other news outlet that covers things that happen on Twitter (which is most of them) also covered the debate, because it started as Ahmari’s Twitter hissy fit. You could reconstruct a whole Rashomon-style account of the debate from these pieces alone, except that the debate is on YouTube and extremely easy to just find and watch. Here’s the response from National Review, obviously on French’s side:

“Ahmari says he wants to “fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.” Okay. But what does that actually mean in practice? What does a “defeated enemy” look like? By what mechanism is the “public square re-ordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good”? Which “public square”? — there are many in America. And what is the “common good and ultimately the Highest Good”? Who decides? Ahmari? The Pope? Nicolás Maduro?”

I’m not inclined to agree with the Review very often, but they’re correct here. Ahmari wrote his tweets and his later First Things piece out of anger, and because of that, it’s obvious in his writing and in the debate that he hasn’t thought anything through in terms of how to accomplish what he sets out. He says liberalism is bad and we need reactionary politics, but how? Are we going to execute all of the drag queens for supporting the public library system? Is that where he’s going? Ahmari couldn’t really answer these questions directly. He spitballed some stuff during the debate about getting the head of the ‘Modern Library Association’ in front of Congress for tough questioning, but that’s half of an idea at best; Ahmari probably meant the American Library Association instead of the thing he said that doesn’t exist, and also the American Library Association is basically a trade group and doesn’t govern public libraries. Reason magazine had a much funnier way of putting all of this: “The First Thingsers believe conservatives should take a different approach and…do what, exactly? Start punching leftists? Form some sort of theocratic street squad that terrorizes librarians who invite drag queens to read to kids?”

The other issue with Ahmari's half-proposal about Congressional investigations is that it's also not new, either to conservatives or to Catholics: Congress has a long and proud tradition of holding hearings on things that make them angry, they just tend to do it after more significant events than Drag Queen Story Hour. For example, in 1999, after the Columbine shooting, there were Congressional hearings on violence in pop culture and how it was being marketed to minors. One of the people who testified was Denver Archbishop Charles Chaput - who often contributed to First Things and National Review throughout his career - who said before Congress:

"People of religious faith have been involved in music, art, literature, and architecture for thousands of years because we know — from experience — that these things shape the soul. And through the soul they shape our behavior. The roots of violence in our culture are much more complicated than just bad rock lyrics or brutal screenplays...But common sense tells us that the violence of our music, our video games, our films, and our television has to go somewhere, and it goes straight into the hearts of our children to bear fruit in ways we can't imagine."

The three most common cultural punching bags in those 1999 hearings were the film The Matrix - since it depicted people in trenchcoats using guns - and two albums that Klebold and Harris appeared to reference in their journals: Marilyn Manson’s Antichrist Superstar and, you guessed it, Nine Inch Nails' The Downward Spiral. In fairness to Chaput, he made it clear that he wasn’t criticizing specific artists as much as broader cultural contributions to violence in America. In fairness to me, Chaput recirculated his testimony after a rash of mass shootings in 2019, specifically because he thought it was a good argument against tightening gun control regulations, even those with overwhelming popular support. As he put it:

“Only a fool can believe that “gun control” will solve the problem of mass violence. The people using the guns in these loathsome incidents are moral agents with twisted hearts. And the twisting is done by the culture of sexual anarchy, personal excess, political hatreds, intellectual dishonesty, and perverted freedoms that we’ve systematically created over the past half-century.”

In other words, Chaput, like all of these guys, also doesn’t give a shit about the “consent of the governed”. Chaput also used 2019 to write the forward to Ahmari's book, firmly establishing Ahmari in this same intellectual tradition as Chaput, Neuhaus, and other Catholics who tend to see democracy as inconvenient. If I keep bringing the same names up over and over again when discussing this intellectual tradition, it’s because the ‘tradition’ is really just only twelve guys repeating the same ideas to each other over and over again. It’s such a small world, and yet these men are given big and influential platforms when they don’t know how to do anything except use a word processor and occasionally get mad at Twitter.

The best critique of the entire Ahmari/French debate came from Osita Nwanevu of The New Republic, who hits it exactly on the head on how Ahmari continues the conservative tradition that was always there:

“It is the Ahmarists, not the Frenchists who will be poised to inherit the movement and do the slaying from here on out, not only because their more openly illiberal attitudes sit better with the right’s new populism but because, ironically, those attitudes spring from conservatism’s deepest, sturdiest roots: The defenses of old hierarchies that led early conservative thinkers like Edmund Burke to regard the then-woolly and new ideals underpinning classical liberalism and its revolutionary proponents with deep caution and often open suspicion.”

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter whether Ahmari thinks any of this through. He doesn’t ever have to, it’s not his job to think up policy, or to ever think about this incident again. He just has to shit out another column on deadline about literally anything he wants. And maybe he’ll upset the wrong person at the New York Post or the Catholic Herald someday and they’ll have to let him go with a nice severance package, and then he’ll just get the same gig at First Things or National Review, who would be more than happy to have him and build out their “ideological diversity”. His actual life story and spiritual journey are unique to his industry, and could have led somewhere fascinating; he sees what he’s doing now as an extension of that journey, but it’s just led to the exact same ideas that everyone else has already had, built on rage and nostalgia, the two things Ahmari was supposed to have outgrown.

EPILOGUE

I wanted some sort of really powerful quotation in the epilogue to have as a parting shot, and there are a few good options. One option was to return to Ahmari’s book and revisit his account of acting in a school play in Tehran, where he writes, about the teacher he didn’t like, “I decided that it was worth it to mouth his stilted, hackneyed dialogue—the theme was Sunni villainy and Shiite victimhood—if it meant stage stardom," and then I would tie that to his broader story about a man who said he would learn about Catholicism, clearly learned nothing, and then became an editor at the Catholic Herald.

Or, also from his book, a saying from Ahmari’s architect father: “"Better to be definite and wrong than to pussyfoot around with the pencil,” and then I’d say something about how he definitely pulled that off with his drag queen spat. Or, when Ahmari describes his frustrations with his new American classmates, “Wasn’t the point of social life to discuss politics, art, and ideology? In America, my ability to parrot the elevated talk of adults was severely undervalued, because the adults themselves weren’t all that into elevated things," I could turn that into something about a successful newspaper writer who wants to spend all day talking about Sacramento Drag Queen Story Hour. Or when he wrote “At my progressive law school, I won notoriety as some sort of “neocon”. I took it as a compliment. The original neoconservatives’ journey, from the radical fringes in the 1930s to the American mainstream by the ’60s, rhymed with my own," I could use that to put together a hypothesis on how he never grew beyond being a dickish contrarian.

But this leaves out all of the philosophers that Ahmari has digested over the course of his life. One of his earliest influences, when he was a teen, was Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, and I’m pretty sure I could pick something like “the people have ye served and the people’s superstition - NOT the truth! - all ye famous wise ones! And just on that account did they pay you reverence,” and then be all like “get it, Sohrab? This is you, dude. This is what you sound like.” And of course, Ahmari was a Marxist for a few years, so I could also go with “the work of the proletarians has lost all individual character, and consequently, all charm for the workman. He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him,” which I can just present while gesturing vaguely to Ahmari’s entire professional output.

Ultimately, though, since Ahmari turned out to be just another boring neocon columnist, and since I've now read so many First Things essays that I have indigestion, I can once again borrow from the great philosopher Trent Reznor for my final thoughts on Sohrab Ahmari: he has let me down. He has made me hurt.

Grift of the Holy Spirit is a series by Tony Ginocchio detailing stories of the weirdest, dumbest, and saddest members of the Catholic church. You can subscribe via Substack to get notified of future installments. The current series covers personalities in right-wing Catholic media.

Sources used for this piece include:

Sohrab Ahmari, From Fire, By Water: My Journey to the Catholic Faith (2019)

Nine Inch Nails, The Downward Spiral (1994, deluxe reissue in 2004)

First Things - “Against David French-ism” (2019)

Institute for Human Ecology - “Cultural Conservative: Two Visions Responding to the Post-Liberal Left” (2019)

The Independent - "Obituary: Monsignor Alfred Gilbey" (1998)

Splinter - “Who is the New York Times Woeful Opinion Section Even For?” (2017)

Vox - “The Real Problem With the New York Times Op-Ed Page: It’s Not Honest About U.S. Conservatism” (2018)

First Things - "The End of Democracy?" (1996)

First Things - "The Future of the End of Democracy" (1999)

First Things - “Winning Semi-Ugly” (2001)

First Things - “Citizens United v. FEC and Christian Liberty” (2010)

First Things - “2013 Supreme Court Roundup” (2013)

The New Republic - “The Magazine of American Theocracy” (2019)

The New Republic - “The Right Wing’s Cultural Civil War is a Drag” (2019)

National Review - “Okay, Sohrab Ahmari, But Why Did You Snap?” (2019)

Reason - “David French is Right” (2019)

Archbishop Charles Chaput - "After The Tragedy At Columbine High" (1999, reprinted in Catholic Education Resource Center)

Archdiocese of Philadelphia - “Gilroy, El Paso, Dayton - and Columbine” (2019)