Rakhat and Reconciliation

It's been twenty-five years since The Sparrow came out, and maybe the church should talk about it

[a note on content: if you haven’t read the 1996 novel The Sparrow yet, this piece will basically cover the entire plot and it gets pretty dark.]

If you're like me and live at some sort of embarrassing intersection of "Catholic nerd" and "sci-fi nerd", your favorite book is probably The Sparrow, the 1996 debut novel by former anthropology professor Mary Doria Russell that tells a story about Jesuits in space. Set in the advanced and enlightened age of - ah - 2019, Russell's much-decorated cult novel begins with SETI picking up definitive signs of intelligent life in the Alpha Centauri system. As world governments scramble to process this epoch-defining discovery, Jesuit priests immediately organize an interstellar expedition to a newly discovered planet. The reason, as Russell lays out in the novel's prologue, is obvious:

“It was predictable, in hindsight. Everything about the history of the Society of Jesus bespoke deft and efficient action, exploration, and research. During what Europeans were pleased to call the Age of Discovery, Jesuit priests were never more than a year or two behind the men who made initial contact with previously unknown peoples; indeed, Jesuits were often the vanguard of exploration...the Jesuit scientists went to learn, not to proselytize. They went so that they might come to know and love God’s other children. They went for the reason Jesuits have always gone to the farthest frontiers of human exploration. They went ad majorem Dei gloriam: for the greater glory of God.”

The first time I read that passage, I admit that I felt a certain sense of pride. I was a product of Jesuit education myself, and you know what? They had done a lot of cool things! They had explored the world and done important mission work and gone out to scary undiscovered places and brought the word of God to the people who lived there, all for God’s glory. A novel extending the proud tradition of Catholic exploration to interstellar travel and alien civilizations sounded cool as hell.

I would say that right now is a difficult time to feel something like “pride” in something like “the tradition of Catholic exploration”. Over the past year, and especially as worldwide protests for racial justice burned over the course of summer 2020, the Catholic church’s track record of gladly participating in injustices throughout American history became a little more public. Specifically, as protestors confronted American institutions for their history of violence against oppressed people, the Catholic church came into the spotlight for their treatment of indigenous Americans during the European exploration of North America. That treatment, as it turns out, was not great, and it was “not great” in multiple ways across multiple projects throughout the church’s history of exploration and colonization.

Which means that for me, in 2021, reading a novel about the proud tradition of Catholic exploration would not feel great. If you do even a cursory amount of research recently about what Catholics did in the “new world”, you won’t really be jazzed up for a feel-good novel about Catholics exploring a literal new world. At best, reading such a novel would feel hokey, and at worst, it would feel like an exercise in self-delusion and apology for genocide. But, of course, if you've read all the way to the end of The Sparrow - or even to the end of the prologue, which ends with the ominous sentence “They meant no harm.” - you know that the book isn't actually about "the proud tradition of Catholic exploration" at all. It’s a book that asks some tough questions, and now, twenty-five years after its publication, it may have just started asking some tougher questions.

CHAPTER ONE - FINALLY, SOME DEVIANTART

Here's a quick rundown of the plot of The Sparrow, and to help you visualize the action of the novel I've also included some NON-pornographic fan art of the novel that I found on DeviantArt. The protagonist of The Sparrow is a Jesuit priest and linguist named Emilio Sandoz. Here is a picture of Sandoz:

He looks pretty badass, right? He’s got a haunted past and a shaky faith, but after years of bouncing around Jesuit missions worldwide ministering to the poor and studying linguistics, he’s settled in his childhood neighborhood in Puerto Rico, where he’s built up strong friendships with a doctor, an anthropologist, an astronomer, and a computer scientist. The computer scientist is Sofia Mendes, who also causes a lot of sexual tension in Sandoz’s life, since she’s also a stone-cold hottie and here she is serving looks on DeviantArt:

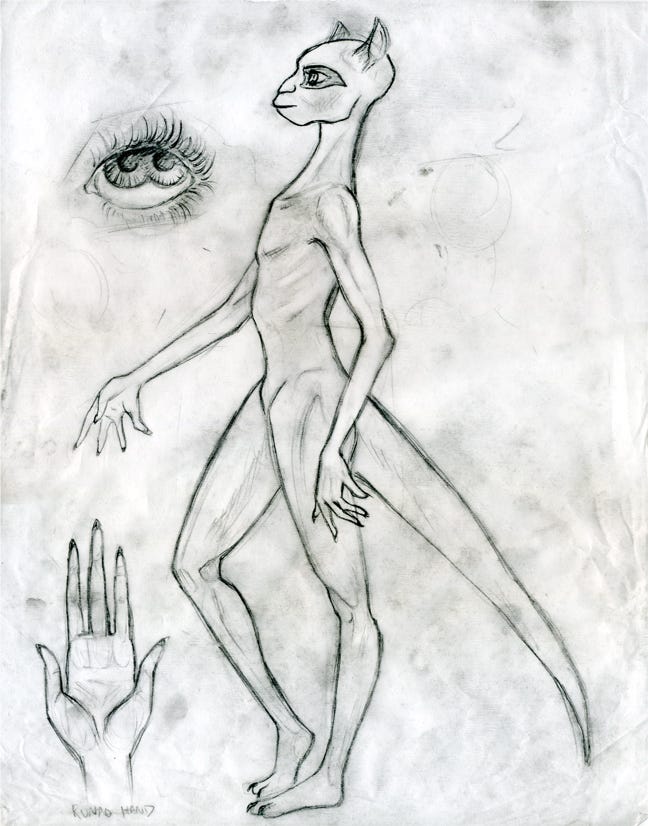

The astronomer friend, who works for SETI, stumbles across a stray radio signal late one night and realizes, to the world’s amazement, that the signal is being broadcast from a planet in the Alpha Centauri system, and is a recording of choral singing by an alien race, suggesting an advanced civilization with radio technology and music composition. As more broadcasts come in, the Jesuits send a team of priest missionaries and join up with Sandoz’s friends to organize a private interstellar expedition to the newly discovered planet of Rakhat. After touching down, the mission makes first contact with the Runa, a peaceful alien race pictured below:

Or pictured here:

Sandoz making first contact with the Runa is an especially moving scene in the novel, as he slowly starts to piece together their language and win over the juvenile members of the Runa tribe with sleight-of-hand magic tricks:

"He felt as though he were a prism, gathering up God's love like white light and scattering it in all directions, and the sensation was nearly physical, as he caught and repeated as much of what everyone said to him as he could, soaking up the music and cadence, the pattern of phonemes on the fly…'God,' he whispered again, eyes closed, with the child settling onto his hip. 'I was born for this!'"

It becomes clear very quickly that the Runa are not the race broadcasting the music, as they don’t speak the same language or possess the technology demonstrated in the radio broadcasts. But the crew slowly makes their way to a city and also makes first contact with the more technologically advanced Jana’ata race, shown here with the Runa for comparison purposes:

Or shown here alongside Sandoz:

The main emissary to the human expedition is the Jana’ata merchant Supaari, eager to make a name for himself in the stratified Jana’ata society by becoming the first person on the planet to greet an alien race. Here’s Supaari:

Throughout the novel, we learn about the anthropology and ecology of Rakhat, as well as the the prayer and spiritual growth of the crew. Permeating the story is the sense that this crew and this mission is providential. Sandoz, specifically, is a priest who carries a lot of doubts with him when it comes to his vocation and his faith, but this incredible discovery, the way the mission comes together, and the harmony of the crew working together starts to reinforce that faith. Here he is at the moment that he learns of the SETI discovery with his friends:

“Entertain, for this extraordinary moment, the notion that we are all here in this room, at this moment, for some reason...Life on Earth is unlikely. Our own experience, as a species and as individuals, is improbable. The fact that we know one another appears to be a result of chance. And yet, here we are. And now we have evidence that another sentient species exists nearby and they sing. They sing."

Here is the crew prepping for the mission, as they draw closer to the launch date and the logistics keep falling into place:

“After a while it became hard to ignore how, against odds, the dice kept coming up in favor of the mission. The crew members went on with their training, their work unaffected by the waxing and waning of confidence, but they all experienced varying degrees of amazement...as the months passed, it was incredibly difficult to resist the beauty of belief.”

And here is Sandoz towards the end of his first interstellar voyage, as Rakhat comes into view:

“One night, I just let myself consider the possibility that this is what it seems to be. That something extraordinary is happening. That God has something in mind for me...and a lot of the time, even now, I think I must be a lunatic and this whole thing is crazy. But, sometimes - Anne, there are times when I can let myself believe, and when I do, it’s amazing. Inside me, everything makes sense, everything I’ve done, everything that ever happened to me - it was all leading up to this, to where we are right now.”

The world is changing, the universe is changing, the biggest event in theological history since perhaps the Resurrection is about to happen, and God’s hand is evident in all of it, even to a man who has always been uneasy about his faith. There are many moving moments like this throughout The Sparrow, as the crew touches down on Rakhat, as they make first contact with the Runa, as two crew members fall in love and conceive a child on an alien world, as the loving crew prays and eats and explores together. For me, though, The Sparrow isn't memorable for its references to Jesuit culture, or its exploration of divine providence, or its original worldbuilding that inspired all that stuff on DeviantArt.

The Sparrow, for me, is notable because it contains the single most bruising tonal shift of any novel I've ever read.

CHAPTER TWO - HEY MAN MAYBE DON’T BUY THOSE SHACKLES

Before we get there, though, we should understand what Catholic exploration actually looked like in some of our history. During the exploration of North America by European powers, the Catholic church was very explicitly supportive of the colonization and subjugation of the new world's indigenous people. This probably isn't a huge shock; the church was also a big fan of slavery and segregation, and their current position on racial equality in America is, and I'll be diplomatic here, fucked.

But supporting colonialism and the exploitation of the native people in the new world was actually part of church doctrine, thanks to two formal papal bulls from the fifteenth century. And in case you're wondering if some of that church doctrine was possibly ambiguous or somehow misinterpreted, it wasn't: the wording from 1542's papal bull Dum Diversas, re-affirmed a year later in Inter Caetera, gave the Spanish government "full and free permission to invade, search out, capture, and subjugate the Saracens and pagans and any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ wherever they may be, as well as their kingdoms, duchies, counties, principalities, and other property [...] and to reduce their persons into perpetual servitude.” This "Doctrine of Discovery" has since been formally denounced, repealed, and apologized for by several Christian denominations, and you'll never guess which church still hasn't done any of that.

So: the Catholic church worked hand-in-hand with European monarchies to explore and settle North America. Colonization and missionary work were closely related, and some of the most famous examples of the latter are the old Catholic missions in what would become California; these missions educated and sheltered indigenous people, and would go on to inspire the architecture of countless Taco Bell restaurants. The Catholic most closely associated with the California mission system was eighteenth-century Franciscan priest Junipero Serra, who was just named a saint in 2015, who is depicted on municipal seals in California, and who is immortalized in statues across the state, including this one where he looks like a super cool and fun guy:

Serra becoming a saint in 2015 was controversial at the time, because in recent years it's become clearer that the California missions Serra ran weren't exactly fun getaway retreat centers for aspiring Catholics. Once an indigenous American converted to Catholicism and moved into the mission, he wasn't allowed to leave, and if he tried, he'd be hunted down, flogged, and returned to doing hard labor at the mission. The expectation for converts was that they would be abandoning their old culture, surrendering their property, and assimilating fully into the new Spanish-conquered world. But who knows how many people actually assimilated fully before they died, since a lot of indigenous people were dying very rapidly at these missions, as disease ran rampant and devastated native populations. Serra's signature is also on purchase orders for shackles at the missions, a testament both to the missions' treatment of indigenous people and the Catholic church's renowned reputation for records retention. Santa Clara professor and Serra biographer Robert Senkewicz summarized Serra's attitudes towards indigenous Americans in an interview with National Catholic Reporter:

"His attitude and behavior were frankly and explicitly paternalistic. Along with probably 99 percent of the people in Europe at the time, he thought that non-Europeans were inferior to Europeans. There was a big debate in the early Spanish empire about whether or not the native peoples were fully rational beings or not. By the time Serra got to the New World, many Spanish thinkers believed that the native peoples of the Americas were in a state of "natural infancy," that they were children. Serra shared that view and he basically had a paternalistic attitude towards them. That paternalistic attitude could, at times, result in a behavior which anybody today would find very hard to justify. If people left the mission without permission, they were pursued and hunted by soldiers and other Indians. If they were brought back, the normal punishment was flogging. What the Spanish military and missionaries thought they were doing was punishing children to make them understand how they should behave."

This is also backed up by a different Serra biographer and history professor, Stephen Hackel, speaking to Smithsonian magazine:

"Indians were expected to give up most of the important aspects of their culture in return for what the missionaries promised them was salvation. Indians who challenged the mission’s authority were flogged. [The missionaries] punished them as children even when they were adults."

So when Serra got approved for sainthood six years ago, indigenous groups objected, and they definitely had a point. Now, Serra didn't personally commit every single atrocity of the Spanish imperial project, and he was acting in a way that was consistent with his era and the church's approval of colonial violence. Maybe that doesn't disqualify him from sainthood - Serra's not even the worst person the church canonized in 2015 - but I feel like it should have disqualified him from the Super-Express Accelerated Sainthood Lane, which is where Pope Francis put him, skipping past several steps to fast-track his canonization. And while Serra didn't do everything bad at the missions that pre-dated and out-lived him, he definitely did some of them, and he is revered in California specifically for his work in the missions, which understandably upset indigenous people in 2015. Again, there are statues of this guy across the state, because of the work he did in the missions, work that we know was inherently violent. One Franciscan priest recognized the recent critiques of Serra as:

"A reevaluation of history and reality...[Serra] has become the personification of all that was bad about the mission system — the decimation of the Native people by diseases, the encounter of the culture. The mission system lasted for around 65 years, and for some, Serra is the embodiment of all of that."

Serra's name and his image have come to symbolize the history of the California missions - just like how others in the past few years came to represent the history of slaveholding interests, or secession - and when you look at the history of the California missions, it's hard to deny that the Catholic church was one of the bad guys here. And all of this came into the spotlight again in 2020, as protests for racial justice sprang up in every city in the country and many Americans reckoned with historical institutional violence that they used to take for granted. Serra’s legacy was part of those confrontations in California, and statues of Serra got torn down like statues of Confederate generals or slaveholders in other parts of the country.

Serra and his fellow missionaries in the new world thought the same things that the characters in The Sparrow thought: that the world was changing, that the universe was changing, that the biggest event in theological history since perhaps the Resurrection was happening, and that God’s hand was evident in all of it, that they were called to do this. And then those missionaries whipped and shackled and killed a lot of people, and entire cultures were eradicated. Somehow, God didn’t stop these atrocities from happening; the Holy Spirit didn’t whisper to Serra “hey man, maybe don’t buy those shackles.” They thought they were on God’s side, but they still did bad things. The missionaries had the same hopeful view of God’s providence as Emilio Sandoz and his crewmates, but it led to oppression and death. So The Sparrow, in 2021, feels like a very different novel than the one I first read years ago, because my relationship to my church has changed, and my understanding of that church’s history has changed. The intrepid explorers of the Catholic church - the real ones - committed atrocities, committed grave sins, against the indigenous people of the Americas. I'm not really qualified to make that call, but Pope Francis is, and he did, in a 2015 speech he gave in Bolivia:

"I say this to you with regret: Many grave sins were committed against the Native people of America in the name of God. I humbly ask forgiveness, not only for the offense of the church herself, but also for crimes committed against the native peoples during the so-called conquest of America."

Pope Francis did take a step towards reconciliation in this address; he recognized the suffering that the church caused in the past, and he understood that this suffering had continuing consequences that demanded some response. He acknowledged that, through the church's broader history as a colonial actor, there was a lot of abuse, violence, subjugation, bondage, and plague, and if we want to be a church that recognizes and responds to suffering, we can’t just treat our history like the heartwarming moments in The Sparrow. Of course, the other thing about The Sparrow is that I’ve only summarized about half of the novel so far.

CHAPTER THREE - THE SPARROW STILL FALLS

The Sparrow's narrative of first contact with Rakhat is intercut with flash-forward chapters of Emilio Sandoz returning to Earth in 2060. He’s the only member of the mission to return, because all of his crewmates were killed on Rakhat. Many of the Runa are exterminated, Sandoz’s hands have been mutilated, leaving him helpless, and the controversy around a private mission to space launching without the permission of any government has basically led to an almost-collapse of the Jesuit order and the Catholic church more broadly. As another Jesuit priest thinks in the novel: “The mission probably failed because of a series of logical, reasonable, carefully considered decisions, each of which seemed like a good idea at the time. Like most colossal disasters.”

It turns out that Rakhat was a little more vicious than other places that Catholic missionaries have attempted to colonize. A crew contracts a debilitating alien illnesses on the new planet; another appears to be killed by an alien poacher. The remaining crew members, through a series of misunderstandings, inadvertently upset the population balance between the Jana’ata and Runa, triggering a near-genocide of the Runa and the deaths of almost everyone else on the mission. Sandoz is taken prisoner and sold as a slave to another Jana’ata, who sadistically tortures and repeatedly rapes Sandoz, breaking the priest’s psyche. In a cruel irony, the Jana’ata songs, the ones that inspired the interstellar voyage in the first place, turned out to be Jana'ata celebrations of rape and violence, and new ones are written about Sandoz. Once the Jesuits get Sandoz back to Earth, they interrogate him to try and piece together what went wrong on the mission, all while Sandoz contemplates suicide and suffers from post-traumatic night terrors.

Russell deliberately undercuts all of her chapters celebrating God’s providence and the excitement of a once-in-a-lifetime discovery with the dark and brutal details of Sandoz’s torment on two planets. It’s an unbelievable left turn for the novel, and I haven’t found another novel that makes a tonal shift this jarring. Sandoz - and the reader - thought that he had finally stumbled onto God's purpose for him, and instead he - and the reader - gets slammed face-first into abuse, violence, subjugation, bondage, and plague. Hey, wait a second, didn't we just see those words somewhere?

The Sparrow is definitely not a revenge fantasy against the Catholic church for the sins of colonialism, and interpreting it that way would be inconsistent with Russell's own comments on why she wrote the book. But in 2021, it’s hard to ignore that the Jana'ata, on a literal New World, are enslaving and infecting and destroying people who, historically, have done some enslavement and infection and destruction of new worlds themselves. Missionaries who prayed and sang, missionaries who believed in God’s providence, but missionaries who historically committed “grave sins”, now find themselves on the receiving end of those grave sins, which were horrifying to read about when the book came out in 1996, but now take on new meaning when you understand that violence like this was also part of "the proud tradition of Catholic exploration" in real life.

Russell doesn't present the novel’s big turnaround as right or just, she presents it as a tragedy; she even compares Sandoz’s suffering to other Jesuit missionary martyrs like Saint Isaac Jogues. The Sparrow isn’t really about “the proud tradition of Catholic exploration”, it’s about a man who thought he was part of that tradition, has his life and body destroyed instead, and is now trying to work through what his belief in God means now in the light of this tragedy. Sandoz attempts an answer towards the end of the novel:

“If I was led by God to love God, step by step, as it seemed, if I accept that the beauty and the rapture were real and true, then the rest of it was God’s will too, and that, gentlemen, is cause for bitterness. But if I am simply a deluded ape who took a lot of old folktales far too seriously, then I brought all this on myself and my companions and the whole business becomes farcical, doesn’t it. The problem with atheism, I find, under these circumstances, is that I have no one to despise but myself. If, however, I choose to believe that God is vicious, then at least I have the solace to hate God…so many dead, because I believed…”

If Sandoz’s answer to suffering in a world run by a loving God is to find solace in hating that God, well that sounds pretty bleak, but it’s not like anybody else in the novel has a better answer. Three other Jesuits draw a blank in another conversation near the end of the novel:

“So God just leaves? Abandons creation? You’re on your own, apes. Good luck!”

“No, he watches. He rejoices. He weeps. He observes the moral drama of human life and gives meaning to it by caring passionately about us, and remembering.”

“Matthew ten, verse twenty-nine. Not one sparrow can fall to the ground without your Father knowing it.”

“But the sparrow still falls.”

Obviously, the question of “if God is so great, why is there suffering?” is not new, and overall the novel is definitely not perfect: I think the violence gets too over-the-top before the end, Russell is very bad at writing dialect - oh boy a lot of characters speak in dialects - and she also made some weird speculative predictions about a 2019 where Japan had conquered all of Asia because they were inherently “wild gamblers”. And I’ve only been discussing one layer of a novel that contains many layers. But overall, The Sparrow is a memorable and searching response by a person of faith trying to comprehend suffering and brutality and fit it into her understanding of the world, and it's moving to see it in a Catholic novel by a Catholic writer. Except, of course, Russell's not Catholic. She was, once. But she wasn't by the time she wrote The Sparrow.

CHAPTER FOUR - GOD HAS A LOT TO ANSWER FOR

Mary Doria Russell left the Catholic church at age fifteen; when she became a mother and wanted to raise her son in a faith tradition, she converted to Judaism. In an interview shortly after the novel's publication, she explained: "When you convert to Judaism in a post-Holocaust world, you know two things for sure: one is that being Jewish can get you killed; the other is that God won't rescue you." Russell then built off of this idea when explaining the novel's ending:

"What happens to Emilio Sandoz is a holocaust writ small. He survives, but loses everyone...we seem to believe that if we act in accordance with our understanding of God's will, we ought to be rewarded. But in doing so we're making a deal that God didn't sign on to. Emilio has kept his end of a bargain that he made with God, and he feels betrayed. He believes he has been seduced and raped by God, that he's been used against his will for God's own purpose. I guess that's partly what I'm doing with this book. I wanted to look at that aspect of theology. In our world, if people believe at all, they believe that God is love, God is hearts and flowers, and that God will send you theological candy all the time. But if you read Torah, you realize that God has a lot to answer for."

The Sparrow is very explicitly about processing suffering as a person of faith, suffering that doesn't square with your understanding of God. The book is not a revenge fantasy, but it asks some very interesting questions, and through its tonal powerslide, asks them in a very interesting and memorable way. "How do you live as a Catholic (or Christian, or person of any faith) knowing that God isn't going to protect you from atrocities?" is a a very big question, and here it’s coming from a Catholic convert to post-Holocaust Judaism, set against the background of "Jesuits in Space", delivered by head-faking towards an inspiring story of first contact and then spinning into a tragedy of rape and mutilation. Russell was very explicit that she wrote her novel to explore this question. Sandoz thought he was doing God's will in a new world, but ended up enduring brutal suffering, and the author and reader try to get their heads around that over the course of the novel. He’s mad at God, and I don’t blame him. God has a lot to answer for when it comes to Emilio’s suffering.

But God also has a lot to answer for in the suffering caused by the people who worked for him. There are other real people in the Catholic church who, like Sandoz, thought they were doing God's will in a new world, and they ended up causing brutal suffering, and that’s also a tragedy. So when I read The Sparrow in 2021, after I spent some time looking through Catholicism's history, the new question I found in the novel was "how do you live as a Catholic knowing that God isn't going to protect you from committing atrocities?" God has a lot to answer for when people suffer, and God has a lot to answer for when the suffering is being caused in his name. Think about that, and think about it in the context of the people that the Catholic church has caused to suffer before, and the people suffering right now, and whether our church is recognizing and responding to that suffering or excusing it. And think about it in the context of these comments Russell also made in her interview:

"The idea [for the novel] came to me in the summer of 1992 as we were celebrating the 500th anniversary of Columbus's arrival in the New World. There was a great deal of historical revisionism going on as we examined the mistakes made by Europeans when they first encountered foreign cultures in the Americas and elsewhere. It seemed unfair to me for people living at the end of the twentieth century to hold those explorers and missionaries to the standards of sophistication and tolerance that we hardly manage even today. I wanted to show how very difficult first contact would be, even with the benefit of hindsight. That's when I decided to write a story that put modern, sophisticated, resourceful, well-educated, and well-meaning people in the same position as those early explorers and missionaries - a position of radical ignorance."

There's a lot to chew on there. Russell's example of Columbus was a very bad choice, as Columbus was condemned for his cruelty to indigenous people during his lifetime, by the authorities and standards of his era, and is now more broadly viewed by non-Italians as a racist historical villain. But Russell isn't praising Columbus's kindness and mercy in that quote, she's asking me whether I really think I could have done better were I in the same position of "radical ignorance", and I'm not sure I could. The best I could do would be to know that I was in a position of radical ignorance, look to the lessons from our history, and try to avoid the mistakes that the people before me have made. I would have to take extra care, knowing that I don't just get a free pass to do whatever I want as long as I say God is on my side, to make sure that I don't commit any more atrocities.

Serra's - and other missionaries' - approach to colonizing the new world was rooted in radical ignorance. The church may have been acting with the best of intentions, the church may have thought they were carrying out God's will, the church may have been acting consistently with its time, but the historical reality is that the church still committed atrocities, people still died, and cultures were still destroyed. This does not singlehandedly ruin the church's moral leadership in the world, but it does call the leadership of the church to recognize the suffering that people felt at our hands, and to respond to that suffering, as Pope Francis began to do in 2015. If the church today is able to candidly admit what they did wrong in the past, why what they did was wrong, and how we as a church can grow from this and reconcile with the people we have wronged, we can get somewhere. So, as racial injustice was in the national spotlight over the past year, as the church’s history of colonial violence began to attract more attention, all that we really needed was for the leadership of the Catholic church in America to be good at displaying humility and a willingness to learn, change, and reconcile. Boy, I sure hope they were good at that.

CHAPTER FIVE - THEY WERE NOT GOOD AT IT

After the murder of George Floyd in 2020, as part of nationwide protests against systemic racial injustice, activists in California began to topple statues of Junipero Serra across the state. Again, Serra was already a controversial figure before 2020, and as protestors confronted the institutions that had violently enforced racial hierarchy over the course of American history, Serra statues became a stand-in for the broader California mission system, which was the target of justified anger during this national boiling point. The California bishops denounced the property damage - some of them more severely than they did George Floyd’s murder - and a few of them went out of their way to super-denounce it.

San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone had his own "mamma mia" moment when, after publicly calling for aggressive prosecution and jail time for protestors who threatened statues of Serra, he decided to perform a public exorcism in Golden Gate Park, where a Serra statue got toppled by protestors, saying to onlookers that:

“I’ve been feeling great distress and a deep wound in my soul when I see these horrendous acts of blasphemy … and disparaging of the memory of Serra, who was such a great hero, such a great defender of the indigenous people of this land...This is the activity of the evil one who wants to bring down the Church, who wants to bring down all Christian believers."

Again, the historical record isn't especially ambiguous about the material impact of the California mission system on indigenous Americans. Perhaps using Serra as a metonym for an entire broken system is harsh, but I don't think it's as harsh as rushing to call an outpouring of anger during a nationwide reckoning with racial violence "blasphemy", dismissing any anger at the institutional church as "the activity of the evil one", calling Serra an unambiguous "hero", and then doubling down on all of that again:

"There’s ignorance of the real history. So I would ask our people to learn the history of Father Serra, the missions, the whole history of the Church, so they can appreciate the great legacy the Church has given us, given the world: so much truth, beauty and goodness. It’s a wonderful legacy that we should be proud of. There are those that want to make us feel ashamed of it. We have every reason to be proud of it."

You already read in chapter two that I learned a little bit of the history of the missions, and after learning that and writing the first few chapters of this piece, I'm not very proud of that history, and I'm ready to conclude: Salvatore Cordileone needs to ayyyyyyyy shudduppayofaaaaaace. This isn’t new; Cordlieone is an asshole. If you look through any recent political debates in the church, you will always find a statement by Cordileone explaining, in so many words, that the Catholic church is primarily a lobbying arm of Donald Trump and the Republican party. He approaches every political and pastoral question through that lens.

Cordileone, however, is not the dumbest bishop in the country, and he's not even the dumbest bishop in the state of California. That honor, of course - of course! - goes to Los Angeles auxiliary bishop, aspiring media mogul, and star of a future live-action biopic about Mister Potato Head, Robert Barron. On Word On Fire, Barron's stupid website that sucks, he published a 2020 piece titled "Cancelling Padre Serra", where he explained that these protestors were blowing everything out of proportion:

"To state it bluntly, Junípero Serra is being used as a convenient scapegoat and whipping boy for certain abuses inherent to eighteenth-century Spanish colonialism. Were such abuses real? Of course. But was Fr. Serra personally responsible for them? Of course not. I won’t deny for a moment that Serra probably engaged in certain disciplinary practices that we would rightfully regard as morally questionable, but the overwhelming evidence suggests that he was a great friend to the native peoples; that he sought, time and again, to protect them from mistreatment by civil authorities; and that he presided over missions where the indigenous were taught useful skills and were introduced to the Christian faith. To suggest, as did some of those who were petitioning for the removal of his statue, that Serra was the moral equivalent of Hitler and his missions the moral equivalent of concentration camps is nothing short of defamatory."

I applaud Bishop Barron for calling out the grave sin of defamation while also saying "uhh yeah some of the Serra stuff was morally questionable but let's not go into details right now please." He actually does go into it on a separate "Junipero Serra FAQ" page on Word on Fire, answering the question "Why is Serra controversial?"

"Critics of Serra’s project claim that American Indians were compelled to join the missions, essentially as a slave labor force, and were baptized against their will. The consensus of responsible historians, however, is that both of these charges are false. In fact, the vast majority of the Indians recognized the advantage of living in connection with the missions, and only about 10% of those who had come to missions opted to leave. To be sure, those who left were hunted down and, upon their return, were sometimes subjected to corporal punishment. Indeed, there is real evidence that Padre Serra countenanced such violence: in one of his letters, he speaks of the need to punish wayward Indians the way a parent would chastise a recalcitrant child, and in another document, he authorizes the purchase of shackles for the mission in San Diego. Certainly from our more enlightened perspective, we would recognize such behavior as morally wrong, and it is no good trying to whitewash the historical record so as to present Serra as blameless."

That's where the answer ends, and I think if you're trying to defend Serra's legacy and the best you can come up with is "yeah sure he hunted people and kept them in chains," you're losing the argument. Still, I can kind of understand Barron's original point about the protestors, even though he delivered it very poorly: we don't help anyone by using overblown analogies and insane comparisons. Anyways, now that we've established that overblown analogies and insane comparisons are off the table, let's see what Barron writes in his next paragraph of "Cancelling Padre Serra":

"When I saw the videos of Serra statues being torn down, burned, spat upon, trampled, and desecrated in San Francisco and Los Angeles, I shuddered—not only because such behavior was boorish and unjustified, but also because it called to mind very similar activities at earlier stages of American history. In the mid to late nineteenth century, anti-Catholicism was rampant in the United States, due in part to prejudices inherited from Protestantism but also due to the arrival of large groups of immigrants from Catholic countries, who were considered inferior. A powerful political party, the Know-Nothings, was organized precisely around the theme of opposing Catholicism, and in many of the major cities of our country, Catholic convents, parishes, cathedrals, statues, and churches were burned to the ground by unruly mobs. Moreover, in that same period, the Ku Klux Klan, which was active not just in the South but in many northern cities as well, endeavored to terrorize blacks and Jews, of course, but also, it is easy to forget, Catholics. If you doubt that this sort of knee-jerk opposition to Catholicism endured well into the twentieth century, I would recommend you consult some of the histrionic rhetoric used by the opponents of John F. Kennedy during the presidential campaign of 1960. The dean of American historians, Arthur Schlesinger, Sr., summed up this trend in his oft-repeated remark that prejudice against Catholics is “the deepest bias in the history of the American people.”...We are passing through a Jacobin moment in our cultural history, and such periods are dangerous indeed, for there is no clear indication what can stop their momentum."

See, we don't help anyone by using overblown analogies, and in fact, anyone using an overblown analogy is kind of like a Klansman who is coming to exterminate you for your faith. Barron's arguments are characteristically idiotic and self-contradictory, and they're probably better understood through the lens of Barron trying to defend himself to Taylor Marshall and other far-right Catholics who criticized him last year for not doing enough to defend the Serra statues in his state. I covered the Barron/Marshall pissing match in a different piece last year where I compared it to "watching a couple of one-legged men fighting for a chance to hump the same doorknob," and with a year to reflect on it, I'm going to stand by that description. All of this from Cordileone and Barron are the actions of men who have never asked the question that I found in The Sparrow: how do you live as a Catholic knowing that God isn't going to protect you, or your church, from committing atrocities?

A lot of the furor around Serra is out of the spotlight now. The bishops blew their chance to confront their old institutional sins, they blew their chance to recognize real suffering and respond to it, but nobody was really surprised by that. All we can hope is that there isn't another scandal from Catholicism's colonial history that is about to explode imminently, and that if it does explode, the bishops will be good at handling it this time around.

CHAPTER SIX - THEY ARE BAD, ACTUALLY

So here's the new problem, which, like most new problems in the church, is really an old problem that we're only learning about now. Over the past year, Canadian officials have been discovering unmarked mass graves of indigenous children at old boarding schools operated by Christian churches, including the Catholic church. Canadian indigenous communities and their allies are understandably outraged; the mass graves are further evidence of what Canada's Truth and Reconciliation commission called a "cultural genocide" in 2015, a cultural genocide that forced assimilation and included "physical and sexual assault, malnourishment and being punished for speaking Native languages," in the words of one Episcopal priest. The discovery of unmarked mass graves shows the toll of that genocide, perpetrated by people acting in God's name, in visceral detail. Indigenous groups have started protesting, and churches have been vandalized in anger. Now, the full story of the Canadian mass graves is not yet clear, but there is a broad consensus that the story does not contain the line "and then the Catholic church did everything correctly." Pope Francis is currently scheduling a trip to Canada to apologize, again, for the sins of colonialism.

Serra and the residential schools are both colonial projects that the Catholic church participated in, but they are separate projects. These schools are not part of Serra's legacy, and operated after his death - mostly in the 19th and 20th centuries - in different parts of North America. But in both cases, the church has been on the receiving end of outrage from groups that they have historically brutalized, and in both cases the church has an opportunity to respond, reconcile, and possibly grow from this. But the way that the institutional church, and others interested in defending the indefensible, have responded to increased scrutiny of Serra and the initial discoveries in Canada does not give me a lot of hope that they're going to respond to this in a helpful or productive way when similar discoveries happen in the States.

And we have to understand: similar discoveries are going to happen in the States. In response to the Canadian mass graves, the Department of the Interior here in the States is currently launching its own investigation into church-operated indigenous residential schools, including 84 that were run by the Catholic church. Maybe nothing bad ever happened at the American residential schools, but given our church's track record so far on basically everything having to do with the treatment of indigenous Americans, I don't feel great about what the investigation will turn up.

The most depraved and ghoulish response to the Canadian scandal so far has come from The American Conservative, a publication best known for employing underwritten Looney Tunes character Rod Dreher but that also employs people willing to write that those mass graves are "good, actually".

In "The Meaning of the Native Graves" from July 2021, columnist Declan Leary tells readers not to fret about the mass graves, using a simple argument: what else were we supposed to do with all of those child corpses, anyway?

"We have always known that many children died in the residential schools, which were active through the 19th and 20th centuries. Child mortality was relatively high during that period to begin with; Indian mortality overall was astronomically high; and the Church-run schools for native children were systemically underfunded by the government, resulting in subpar facilities and inadequate medical care...The “mass graves” of public hysteria are, in fact, the ordered and intentional burial sites of people we always knew were dead, and who died of more or less natural causes. In more literate times, we might have called that a cemetery. People die, and when they die, you put them in the ground. There is nothing inherently scandalous about this."

Perhaps anticipating that "obviously there are a lot of corpses! A lot of people died!" wasn't going to satisfy everyone - like, for example, anyone asking "ok but how did those people die and was there perhaps any major religious institution with the power to prevent those deaths from happening" - Leary goes on to explain that anything and everything that happened at the residential schools, regardless of the body count, had to have been worth it:

"Make no mistake, the residential schools were first and foremost Christian. Those who ministered to the Indians a century ago did so...out of a sincere concern for the salvation of their souls...Likewise, the certain fact that souls were saved by the missionaries, the enduring belief of Christians that the Gospel is true and must be spread, is paramount; everything else is secondary."

It's difficult for me to overstate how far this is from my understanding of Christianity, or of morality overall. This is very literally an argument that if you say the right magic words, you can kill as many people as you want and it will be okay. It is an argument that rejects any recognition or response to suffering, in favor of political and material dominance. How do you live as a Catholic knowing that God isn't going to protect you from committing atrocities? The answer cannot be to excuse or even celebrate those atrocities, and if it is, then I can't be Catholic anymore. You have to recognize people are suffering. You have to respond to that suffering in front of you.

Is “they were good, actually” the sort of response we should expect to see from our bishops if and when indigenous Americans start getting exhumed? Well, Robert Barron already hinted at something very similar in his earlier piece on "Cancelling Padre Serra":

"It is no exaggeration to affirm that from the missions established by Junípero Serra came much of the political and cultural life of the state of California. Many of our greatest cities—San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Santa Barbara, and yes, Ventura—were built on the foundation of the missions. And I won’t hesitate to say it: the spread of the Christian faith in this part of the world took place largely because of the work of Junipero Serra and his colleagues—and this is a good thing!"

Barron's correct that Serra, and the mission system more broadly, established the foundation for today's cultural life in California. But you already know what the problem is: there was already a culture in California when Serra got there, and it's not really around anymore because most of those people died, and they weren't dying of old age. What are Barron or Leary really celebrating? That Catholic missions were brave enough to spread the faith without regard for the body count among the people they were supposed to be serving? That the missions engaged with a new culture, and decided that their own culture was just good enough to replace the new one entirely? That we happened to have then guns and chains and germs on our side? And as the world keeps heating up and millions of people are displaced across the world and there continue to be violent conflicts between the powerful and the vulnerable, are the leaders of our church once again going to get on the same side as the guns and chains and germs?

Maybe they are. At least, that's the impression I get from USCCB president and Los Angeles Archbishop Jose Gomez, who just gave a speech on November 4th in which he made clear his feelings on the current movements for racial justice in America, and his thoughts on anyone interested in confronting the violence in our past, in anyone interested in recognizing suffering and responding to it:

"The new social movements and ideologies that we are talking about today, were being seeded and prepared for many years in our universities and cultural institutions. But with the tension and fear caused by the pandemic and social isolation, and with the killing of an unarmed black man by a white policeman and the protests that followed in our cities, these movements were fully unleashed in our society...I believe the best way for the Church to understand the new social justice movements is to understand them as pseudo-religions, and even replacements and rivals to traditional Christian beliefs."

So it looks like the official position of the church is quickly becoming "responding to suffering is un-Christian and your liberal college professor probably tricked you into doing it." How do you live as a Catholic knowing that God isn't going to protect you from committing atrocities? It can't be like this.

EPILOGUE

I don't know what's supposed to happen next. The church has hurt people. Not all of the church, and not all of the time, but the church has hurt people, for centuries, in ways which altered the course of world history. I don't know what they're supposed to do about it. I don't know what happens in the truth and reconciliation process from here. The people speaking in God's name today are not telling us that God watches the sparrow fall, they're telling us that we made the sparrow fall and that's fine because it's not like the sparrow was all that impressive anyways and actually a lot of people made a lot of sparrows fall back in that era so it's okay that we did too and we just shouldn't ever talk about those sparrows again and we don't have to pay any attention to the current batch of sparrows dropping from the sky, either.

How do you live as a Catholic knowing that God isn’t going to protect you, or your church, from committing atrocities? I don’t know the right answer, but I’ve recently learned the wrongest possible answer, which is "claim that the atrocities never actually happened, and that if they did happen, they were good, actually, and that everyone who is mad about them is being very Satanic and anti-Catholic." And that's what the church leadership is doing right now, certainly in the States: they're finding the worst possible response to this moment in history and hitting it as hard as they can, and as long as they're doing that, the institutional church is a barrier to anything resembling justice in our country today.

One piece of Serra's story sticks with me. In 1775, while Serra was still running the California missions, there was a revolt of indigenous people at the San Diego mission. According to Professor Senkewicz, after the mission got razed, "Serra wrote to the viceroy and asked that, if he were to be killed by an Indian, that Indian ought not be executed but forgiven." I don't know what was in Serra's head when he wrote that letter. But I like to think that somewhere in Serra's missionary work, he got a brief glimpse into how the Spanish colonial project, and its treatment of indigenous people, would be seen by people in the future. Maybe he asked how he should live as a Catholic, knowing that God wasn’t going to stop him from committing atrocities, and that maybe he had already committed some. And maybe his answer was to try to take one step toward mercy and reconciliation, to surrender any sense of feeling right, in order to properly recognize and respond to suffering. If that’s what he was thinking, it doesn't automatically make him a saint, but it does put him a step closer to sainthood than I am. Anyone else who wants to get there could maybe start by reading a twenty-five year old book about aliens.

Grift of the Holy Spirit is a series by Tony Ginocchio detailing stories of the weirdest, dumbest, and saddest members of the Catholic church. You can subscribe via Substack to get notified of new installments.

Sources used for this piece include:

Barron, Robert. “Canceling Padre Serra.” Word on Fire, 24 Aug. 2020, https://www.wordonfire.org/resources/article/canceling-padre-serra/27935/.

Barron, Robert. “St. Junípero Serra FAQ Page.” Word on Fire, 14 Oct. 2021, https://www.wordonfire.org/serra/.

Blakemore, Erin. “Why Are Native Groups Protesting Catholicism's Newest Saint?” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 23 Sept. 2015, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-are-native-groups-protesting-catholicisms-newest-saint-180956721/.

Escobar, Allyson. “Controversial Junípero Serra Supported by Some Indigenous Catholics, California Mission Workers.” National Catholic Reporter, 11 Aug. 2020, https://www.ncronline.org/news/justice/controversial-jun-pero-serra-supported-some-indigenous-catholics-california-mission.

Gomez, Jose. “Reflections on the Church and America's New Religions.” Archbishop Gomez, https://archbishopgomez.org/blog/reflections-on-the-church-and-americas-new-religions.

ICT Staff. “Pope Francis Apologizes to Indigenous Peoples for 'Grave Sins' of Colonialism.” Indian Country Today, Indian Country Today, 10 July 2015, https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/pope-francis-apologizes-to-indigenous-peoples-for-grave-sins-of-colonialism.

Leary, Declan. “The Meaning of the Native Graves.” The American Conservative, 7 July 2021, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/the-meaning-of-the-native-graves/.

Lind, Dara. “Junipero Serra Was a Brutal Colonialist. so Why Did Pope Francis Just Make Him a Saint?” Vox, Vox, 24 Sept. 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/9/24/9391995/junipero-serra-saint-pope-francis.

Murphy, Alyssa. “Archbishop Performs Exorcism Where St. Junípero Serra Fell, Asking for God's Mercy.” National Catholic Register, EWTN, 29 June 2020, https://www.ncregister.com/blog/archbishop-performs-exorcism-where-st-junipero-serra-fell-asking-for-god-s-mercy.

Reese, Thomas. “California Bishops Should Ask, 'What Would Junipero Serra Do?'.” National Catholic Reporter, National Catholic Reporter, 1 Nov. 2021, https://www.ncronline.org/news/opinion/california-bishops-should-ask-what-would-junipero-serra-do.

Reese, Thomas. “Junipero Serra: Saint or Not?” National Catholic Reporter, 15 May 2015, https://www.ncronline.org/blogs/faith-and-justice/junipero-serra-saint-or-not.

Rotondaro, Vinnie. “Doctrine of Discovery: A Scandal in Plain Sight.” National Catholic Reporter, 5 Sept. 2015, https://www.ncronline.org/news/justice/doctrine-discovery-scandal-plain-sight.

Russell, Mary Doria. The Sparrow (20th Anniversary Edition). Ballantine Books, 1996/2016.

Salvadore, Sarah. “Franciscans Grapple with Colonial Legacy of Junípero Serra.” National Catholic Reporter, 24 July 2020, https://www.ncronline.org/news/accountability/franciscans-grapple-colonial-legacy-jun-pero-serra.

Smith, Peter. “US Churches Reckon with Traumatic Legacy of Native Schools.” AP NEWS, Associated Press, 23 July 2021, https://apnews.com/article/canada-religion-e25769edc81d8e1e6639c8960be613d7.