Ordinary Timequake

In a blogging first, a 34-year-old white dude talks about how he likes Kurt Vonnegut.

"My great war buddy Bernard V. O'Hare, now deceased, lost his faith as a Roman Catholic during World War Two. I didn't like that. I thought that was too much to lose."

-Kurt Vonnegut in Timequake

There was a moment earlier this summer when it felt like the world was maybe going to change for the better. People were getting vaccinated, infection rates were going down, and the past year or so, the slow-motion calamity that hadn't ever happened before in our lifetimes, was coming to a close. My family was all breathing a collective sigh of relief; my sister was getting married in November and it looked like we would be able to celebrate free from worries about the virus. A really exciting part of it for me, though, was the idea that we had lived through an event big enough to change the world, and that the other side of all of this would be different, that the world that came out of this would be different than the world in which I grew up. It felt like we were all entering an unwritten future, and that we had the power to write something good into that future. In late 2020, Pope Francis, with his biographer Austen Ivereigh, literally did write something good into that future when he published Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future, in which he urged the world to move into this new era with an aim toward building a more compassionate and human world than the one we had before the pandemic:

"I see an overflow of mercy spilling out in our midst. Hearts have been tested. The crisis has called forth in some a new courage and compassion. Some have been sifted and have responded with the desire to reimagine our world; others have come to the aid of those in need in concrete ways that can transform our neighbor’s suffering. That fills me with hope that we might come out of this crisis better. But we have to see clearly, choose well, and act right."

Pope Francis was one of the only world leaders of any kind, anywhere, who responded to the pandemic in a way that made me feel hopeful for the future. He was one of the only ones who didn't talk like he wanted the world to go back to "normal", he knew that "normal" was causing terrible suffering and that "normal" had made the pandemic much worse. He wanted the world to change, permanently, as a result of the pandemic. As the pandemic came to an end, we had the sort of opportunity that the world hadn't had since the end of the second World War, an opportunity to see clearly, choose well, and act right, and to enter a new era as a result. I hadn't seen the world rebuild itself before. I was kind of looking forward to it.

But you know what happened instead: the pandemic didn't end. We reset and had to do the whole fucking thing all over again, the hard way, minute by minute, hour by hour, month by month, staying in our homes again, nervously checking case counts again, watching anti-mask protests again, worrying about our children and our grandparents again.

During that time when I thought the world was changing, I did get to travel once: I drove to Indianapolis one weekend in July to visit family. And while I was there, I also got to visit the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library.

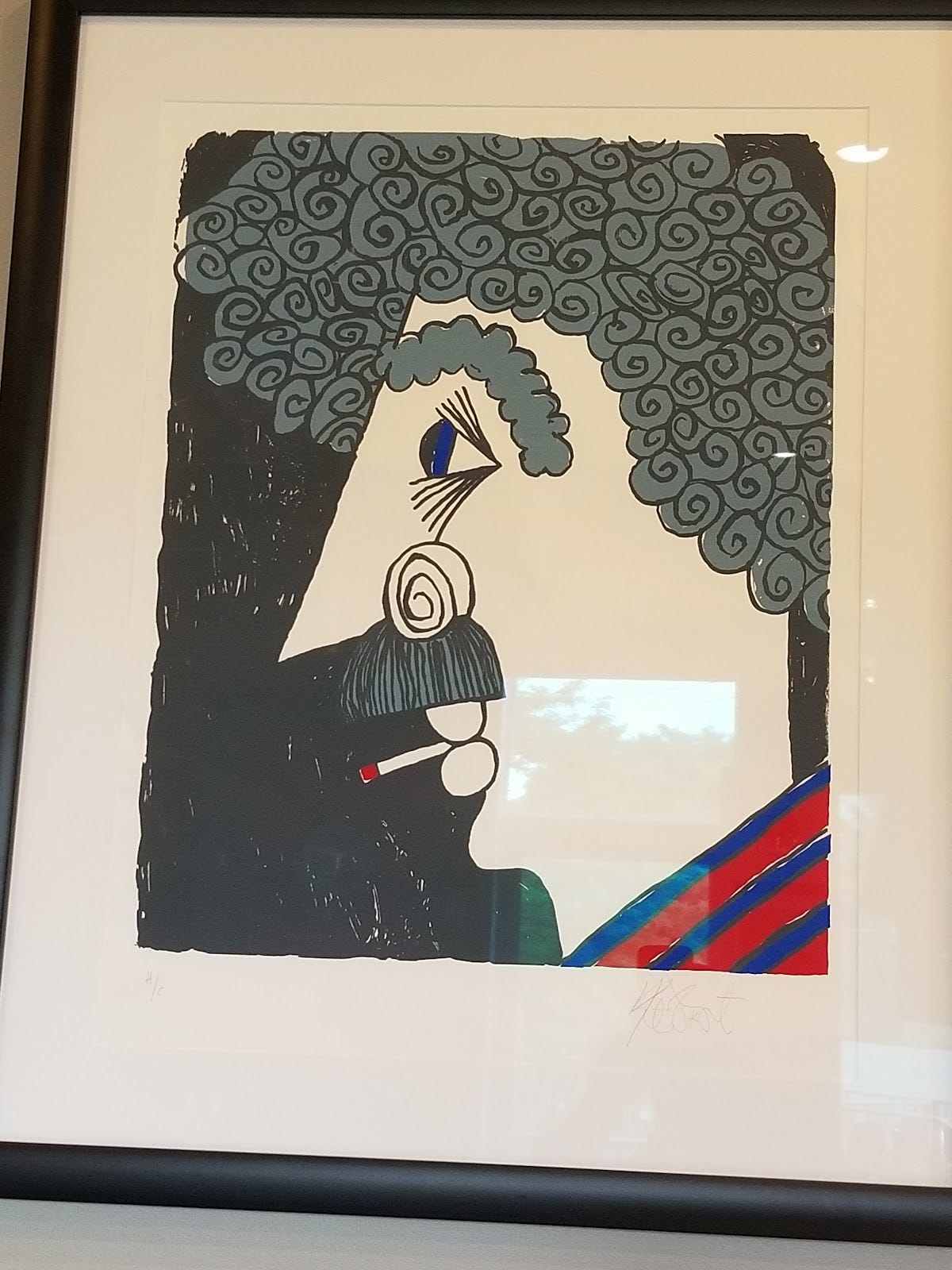

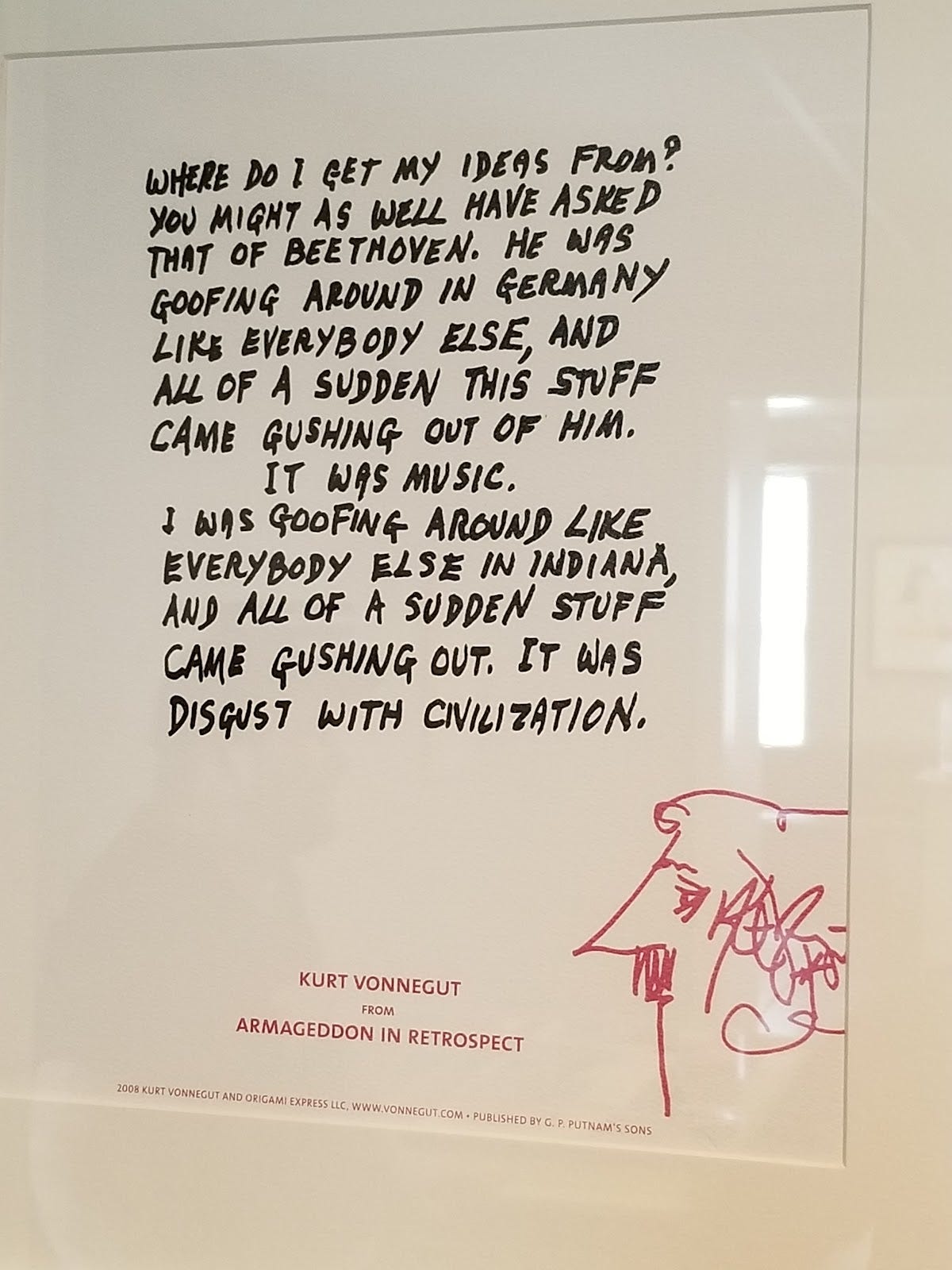

Every famous author has fans, but very few of them earn the cultish devotion and moral authority that Kurt Vonnegut still has fifty years after his most famous works hit bookshelves. All of Vonnegut's work is still in print, a documentary film on his life was just released a month ago, and his Indianapolis museum is swarmed by dedicated readers, many of whom are my age or younger, some of whom bear tattoos of his artwork and illustrations, all of whom are still looking for guidance from him on how we should treat each other. Some of them also stop at the gift shop and buy a tiny stuffed Kurt Vonnegut while they're visiting.

While Vonnegut's work spanned formats and genres, it was always very moral. He always had something he wanted to tell you, directly, about how we should treat each other, and he wrote these lessons out, usually very explicitly, in each of his novels. After I visited the museum in July, I decided to go back and read/re-read all fourteen of his novels afterwards to revisit those moral lessons, and every single one of them, as it turns out, is still one hundred percent true. While I had read Vonnegut's most famous works before, my journey through his deeper cuts this year took me through lessons on how excusing and ignoring fascism just helps fascism grow (Mother Night, 1961), on how the labor movement can save us from a life of gloom and loneliness (Player Piano, 1952), on how we're destroying our planet and barreling towards ecological collapse (Galapagos, 1985), on how we need to restore a sense of collective responsibility towards other people even if we don't know them (Slapstick, 1975), on how it's a moral failure that billionaires exist (God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, 1965). Vonnegut was best known for the moral clarity and prescient views he wrote into anti-war books like Cat's Cradle and Slaughterhouse-Five; it turns out he had moral clarity and prescient views on a lot of issues.

Vonnegut's final novel was Timequake. We'll get to Timequake in a minute.

My sister still got married in November; we had to wear masks and take a few extra precautions since the pandemic still wasn’t over, but everyone was able to adjust just fine. It was the first time I had been to a Mass, in person, since the pandemic started, which means it was also one of the first times I had been to a Mass since I started writing about my frustrations with the Catholic church. I ran into a few little reminders of those frustrations at this wedding.

My sister happened to get married in the diocese of Madison, Wisconsin. In the week leading up to the wedding, the diocese of Madison actually ended up in the news, since the bishop of Madison, Donald Hying, had just barred all diocesan facilities and schools from hosting COVID vaccine clinics. Hying - whose grinning headshot was up in the wedding church vestibule - said that he did this to avoid wading into a polarized political debate, but this was pretty obviously horseshit: Hying had picked a side in that debate, and Catholic schools who had already put vaccine clinics on the books were ordered by the diocese to cancel them. It's infuriating, of course, that the bishop of Madison was claiming to be neutral in a political debate but obviously picking a side, obviously picking the Republican side, obviously picking the side that contradicted the stated teachings of the church, and obviously picking the side that was likely to prolong needless suffering. But I was reminded of a very similar thing that happened about ten years ago, when the bishop of Madison, now-deceased Robert Morlino, picked a "neutral" side in the debate over Wisconsin's anti-union Act 10 bill, but was obviously picking a side, obviously picking the Republican side, obviously picking the side that contradicted the stated teachings of the church, and obviously picking the side that was likely to prolong needless suffering.

When you become a bishop, nobody asks you to look into what the bishop before you did, to make sure you don’t repeat any of his mistakes. Every single stupid selfish shameful thing the last guy did, you just have to do all over again.

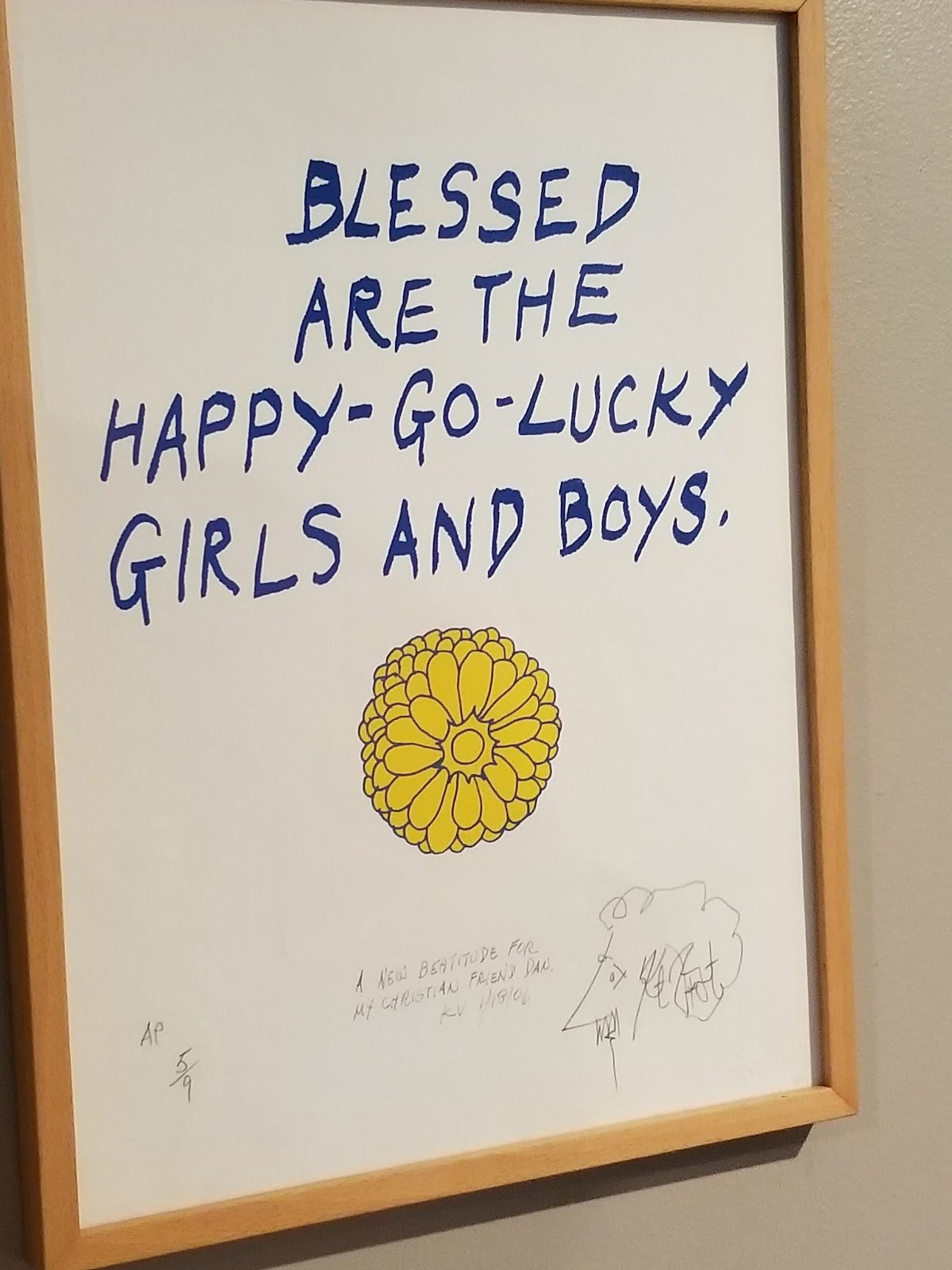

You probably already know this, but Kurt Vonnegut was not Catholic. Actually, Kurt Vonnegut was not Christian. Actually, Kurt Vonnegut was not religious at all, and prided himself on his secular humanist moral compass. But there was one part of the New Testament with which Vonnegut was absolutely enamored, one passage that he considered critical not just to Christianity, but to living as a human being who gave a shit about human beings, one passage that came up incessantly across his fiction and nonfiction works. It was the Beatitudes, the Sermon on the Mount, from chapter 5 of Matthew's Gospel, or, in other words:

"The prediction by Jesus Christ that the poor in spirit would receive the Kingdom of Heaven; that all who mourned would be comforted; that the meek would inherit the Earth; that those who hungered for righteousness would find it; that the merciful would be treated mercifully; that the pure in heart would see God; that the peacemakers would be called the sons of God; that those who were persecuted for righteousness' sake would also receive the Kingdom of Heaven; and on and on."

That summary is from one of his novels, 1979's Jailbird, but Vonnegut was also very upfront about how much value he personally placed in the Sermon on the Mount in his lectures and essays. Here he is in a lecture published in 1981's Palm Sunday:

"I am enchanted by the Sermon on the Mount. Being merciful, it seems to me, is the only good idea we have received so far. Perhaps we'll get another idea that good by and by - and then we will have two good ideas."

And here he is twenty-four years later in the essay collection A Man Without a Country, still enchanted:

"If Christ hadn't delivered the Sermon on the Mount, with its message of mercy and pity, I wouldn't want to be a human being. I'd just as soon be a rattlesnake."

But for Vonnegut, the Sermon on the Mount wasn't merely an enchanting message and it wasn't merely a religious message, it was a political message, and one that was directly in opposition to the political realities of America. Here he is in an essay published in 1991's Fates Worse Than Death, discussing the cultural politics of the Reagan neocons. Let me know if any of this sounds familiar to you:

"...the crazy quilt of ideas all its members had to profess put the Council of Trent to shame for meanspirited, objectively batty fantasias: that it was good that civilians could buy assault rifles; that the contras in Nicaragua were a lot like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison; that Palenstinians were to be called ‘terrorists’ at every opportunity; that the contents of wombs were Government property; that the American Civil Liberties Union was a subversive organization; that anything that sounded like the Sermon on the Mount was socialist or communist, and therefore anti-American; that people with AIDS, except for those who got it from mousetrapped blood transfusions, had asked for it, that a billion-dollar airplane was well worth the price; and on and on.”

When the George W. Bush administration was in power, Vonnegut had some more pointed comments on the Sermon on the Mount in A Man Without a Country, asserting that the Christians in power had forgotten, in his estimation, the most important passage in all of Christianity:

“For some reason, the most vocal Christians among us never mention the Beatitudes. But, often with tears in their eyes, they demand that the Ten Commandments be posted in public buildings. And of course that’s Moses, not Jesus. I haven’t heard one of them demand that the Sermon on the Mount, the Beatitudes, be posted anywhere. ‘Blessed are the merciful’ in a courtroom? ‘Blessed are the peacemakers’ in the Pentagon? Give me a break!”

Vonnegut’s longtime friend and war buddy, Bernard V. O’Hare, wrote in his own essay that the main message of Vonnegut’s works is to plead “that world governments found their rule on something more akin to the Sermon on the Mount than the preachings of those who lead the world to Armageddon.” The Sermon on the Mount was Vonnegut's lynchpin for all of society, for living as a human being who cares about suffering in the world, and the people who were supposed to take it to heart completely abandoned it instead. From another essay in Fates Worse Than Death:

“...the example of Christianity is not encouraging, actually, since it was nothing but a poor people’s religion, a servant’s religion, a slave’s religion, a woman’s religion, a child’s religion, and would have remained such if it hadn’t stopped taking the Sermon on the Mount seriously and joined forces with the vain and rich and violent. I can’t imagine that you would want to do that, to give up everything you believe in order to play a bigger part in world history.”

Look, you don’t need me to tell you this, but this is still a very relevant message for Christians today, and a very relevant message for a Catholic church whose bishops attend campaign rallies with Donald Trump and try to overturn elections. I suppose if you need someone to tell you that this is still a very relevant message for Christians today, you could read Pope Francis, who wrote this in Let Us Dream:

“In times of trial you need to be firm in faith, to stay faithful to what matters. A crisis is almost always the result of a self-forgetting, and the way forward comes through recalling our roots...If you were to ask me what is one of the ways Christianity has gone astray, I would not hesitate: it is to forget that we belong to a people.”

Christianity has forgotten itself and gone astray - and, apparently, Pope Francis thinks it has gone astray in multiple ways. The COVID pandemic, in which many of our bishops abandoned any sense of collective responsibility when it came to controlling mass gatherings, encouraging the faithful to get vaccinated, getting themselves vaccinated, or acknowledging that this was a global crisis that might require us to think differently about how our society was structured, brought this all out into the open. We do not treat the poor, the sorrowful, the meek, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the merciful, the pure of heart, the peacemakers, or the persecuted - and the pandemic created more of each of these people - as “blessed”.

During my sister's wedding Mass, I walked around in the vestibule of the church a little bit with my very chatty toddler. The parish had a stack of free faith formation CDs, including one called "Why I Left Planned Parenthood", recorded by Abby Johnson. Being reminded of Abby Johnson made me wonder if she had ever recorded a second album and titled it "Why I Tried to Murder the Vice President" (basically the Pinkerton to her leaving-Planned-Parenthood Blue Album). See, about ten years ago, Abby Johnson tried to make a career out of anti-abortion activism, and it all led her to being part of a mob at the Capitol trying to hang Mike Pence earlier this year. I wasn't really surprised when that information came out; Johnson was just following the same path that Randall Terry and other anti-abortion activists before her have paved, she had the same lust for power and notoriety that led to the same political violence.

When you become an anti-abortion activist, nobody asks you to look into what the activists before you did, to see if anyone else damaged whatever moral credibility the anti-abortion movement could have had, by doing the exact same thing that you’re planning to do right now. Every single stupid selfish shameful thing the last guy did, you just have to do all over again.

The Sermon on the Mount didn’t just show up in Vonnegut's essays; it was also woven into his fiction. You saw the earlier summary from Jailbird; that novel opens with some words of wisdom from real-life labor leader Powers Hapgood. Hapgood - a man who came from money and got an education at Harvard before spending his life fighting for the working class - got dragged into court after getting into a brawl on a picket line, and was asked by the judge “why would a man from such a distinguished family and with such a fine education choose to live as you do?” Hapgood simply responded “because of the Sermon on the Mount, sir”, and the fictional protagonist of Jailbird echoes this response in his own HUAC hearing.

Vonnegut also brought up the Sermon on the Mount in his novel God Bless You Mr. Rosewater, but he worked in the opposite direction as Jailbird: here, one of the characters is an attorney whose job it is to convince rich people to reject the Sermon on the Mount so they can more easily hold onto their wealth:

“One of the principal activities of this firm is the prevention of saintliness on the part of our clients. You think you’re unusual? You’re not. Every year at least one young man whose affairs we manage comes into our office, wants to give his money away. He has completed his first year at some university. It has been an eventful year! He has learned of unbelievable suffering around the world. He has learned of the great crimes that are at the roots of so many family fortunes. He has had his Christian nose rubbed, often for the very first time, in the Sermon on the Mount...History tells us this...giving away a fortune is a futile and destructive thing. It makes whiners of the poor...and the donor and his descendents become undistinguished members of the whining poor.”

Vonnegut’s personal politics were not some big secret. He believed and professed that truly grasping the Sermon on the Mount was inconsistent with being rich and powerful, or being a neocon, or waging war. Who is Vonnegut’s example of the man - other than Jesus - who best lived the values of the Beatitudes? The answer, as he has given multiple times, was legendary labor organizer and Socialist politician Eugene Debs. In his novella God Bless You Dr. Kevorkian, Vonnegut actually gets to meet Debs in the afterlife, who asks him “how the Sermon on the Mount was going over these days.”

If that’s not enough for you, the protagonist of Vonnegut’s 1990 novel Hocus Pocus is literally named after Eugene Debs, and at one point jokes with a friend about socialism in a conversation that ends with “What could be more unAmerican, Gene, than sounding like the Sermon on the Mount?” The epigraph of Hocus Pocus is Debs’ most famous quote: “As long as there is a lower class, I am in it. As long as there is a criminal element, I am of it. As long as there is a soul in prison, I am not free.” Vonnegut describes that famous Debs quote as “such a moving echo of the Sermon on the Mount” in his subsequent novel.

Pope Francis doesn’t mention Eugene Debs in Let Us Dream, of course, but when he talks about Christianity going astray and the global crisis testing all of us, he also offers us this way out, and it's not hard to hear these words in the voice of a hero of the American labor movement:

“Today we have to avoid falling back into the individual and institutional patterns that have led to Covid and the various crises that surround it: the hyperinflation of the individual combined with weak institutions and the despotic control of the economy by a very few...This crisis has called forth the sense that we need each other, that the people still exists...The feeling of being part of a people can only be recovered in the same way as it was forged: in shared struggle and hardship...Unless we accept the principle of solidarity among the peoples, we will not come out of this crisis better.”

The way out is shared struggle and solidarity, which sure sounds like the kind of thing Eugene Debs would say while leading a railroad strike. The way out is recognizing that as long as there is a lower class, we are in it; the way out is rushing to the side of those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, to struggle with them. It was easy for me to agree with Vonnegut connecting Debs and the Sermon on the Mount in his final novel, and to do so in this moment when we need solidarity and the Beatitudes very badly.

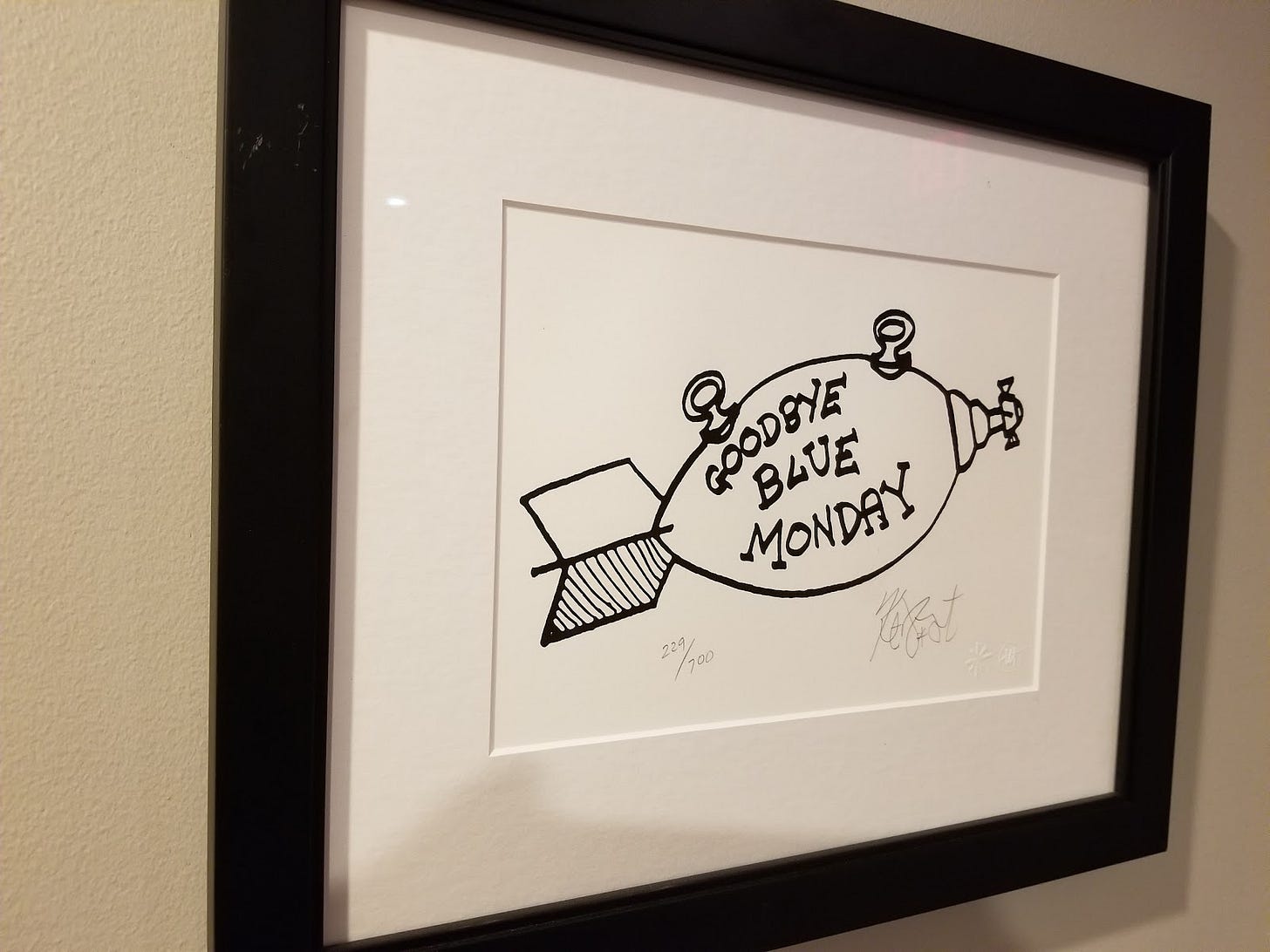

Vonnegut's final novel is 1997's Timequake, the book where the first chapter says “Jesus said how awful life was, in the Sermon on the Mount: ‘Blessed are they that mourn’, and ‘Blessed are the meek’, and ‘Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst for righteousness’,” and the book where everyone has to repeat all their awful mistakes all over again.

The week after my sister's wedding, the full USCCB met in Baltimore for their first in-person meeting in two years. USCCB president Jose Gomez’s opening address asserted that “we are living in a moment when American society seems to be losing its ‘story’. For most of our history, the story that gave meaning to our lives was rooted in a biblical worldview and the values of our Judeo-Christian heritage”. This was kind of a weird address since it used the vocabulary of white nationalism, but it would be jumping to conclusions to say that Gomez had embraced white nationalism based on one speech. However, if he had given another speech two weeks earlier in which he had broadly denounced Americans demonstrating for racial justice as being brainwashed by liberal professors into following "pseudo-religions, and even replacements and rivals to traditional Christian beliefs” - which he did - then yes, you might be on safer ground saying that the president of the USSCB was starting to embrace white nationalism. But none of that is really new. Gomez was really just echoing comments made by the Archbishop of Portland or the Archbishop of San Francisco a year earlier, when church leaders saw a nationwide explosion of anger at American structural injustices and responded by saying "ugh can you shut up please". And that response, of course, was just the natural extension of the church's treatment of Black Americans or indigenous Americans throughout history.

Anyways, the bishops spend a good chunk of their November meeting debating whether they should be denying Communion to Joe Biden because of his views on abortion policy. It was the same debate they had in 2004 when John Kerry ran for president. It was the same debate they had in 1984 when Geraldine Ferarro ran for vice president. The 2021 debate accomplished about as much, politically and theologically, as those previous debates had.

When you become president of the bishops’ conference, nobody asks you to look into what the other bishops did, or if anyone thought those guys actually accomplished anything, or if there’s anything in the church’s history you should be aware of to make sure you don’t repeat any of the old mistakes. Every single stupid selfish shameful thing the other guys did, you just have to do all over again.

Timequake, Vonnegut's final novel, is full of first-person asides and reflections from a revered writer nearing the end of his career, but the title event and the actual plot of the novel are deceptively simple. In February of 2001, there was a blip in the space-time continuum, and everyone suddenly got zapped back ten years into the past. And then they had to live their lives, all over again, for ten years, up to February of 2001, exactly the same way they had before:

“A sudden glitch in the space-time continuum made everybody and everything do exactly what they’d done during a past decade, for good or ill, a second time. It was deja vu that wouldn’t quit for ten long years. You couldn’t complain about life’s being nothing but old stuff, or ask if just you were going nuts or if everybody was going nuts. There was absolutely nothing you could say during the rerun, if you hadn’t said it the first time through the decade. You couldn’t even save your own life or that of a loved one, if you had failed to do that the first time through. I had the timequake zap everybody and everything in an instant from February 13, 2001, back to February 17th, 1991. Then we all had to get back to 2001 the hard way, minute by minute, hour by hour, year by year, betting on the wrong horse again, marrying the wrong person again, getting the clap again.”

Free will is gone. Everyone's life is completely written out for ten years. And not necessarily everyone's best ten years, either: a wrongfully convicted man who was later exonerated by DNA evidence is zapped back into a solitary confinement cell and has to once again serve time for years before being exonerated. People get divorced again and lose their jobs again and bury dead relatives again. The main reaction across all of humanity to this timequake, though, is not despair or horror, it's boredom. Everyone knows exactly everything that's going to happen to them, for every second of the next ten years, and they just have to involuntarily do it all again in real time, while locked in their bodies, for a decade.

You know what else is boring? A pandemic that's going to last at least two years. Pope Francis was more poetic when he described the pandemic as "the patient struggle that burns away all arrogance," but there have been a lot of days where we've been able to guess exactly what's going to happen, exactly what some elected official or boss or landlord is going to do, because it's going to be the same thing that happened before, all the stupid selfish shameful things that we've already seen and have to see again, and it's difficult not to feel apathetic.

You know what else is boring? A church whose leaders ignore the suffering caused by the crisis and just try to score their own political points instead, maybe because they like power, maybe because they like white nationalism, maybe because they've been reading too much garbage on the internet. This isn't the most urgent critique of the church given the suffering they can ignore or enable, but still: these men are boring. There have been a lot of days in the Catholic church during this pandemic where we've been able to guess exactly what's going to happen, what some bishop or priest or YouTuber is going to do, because it's going to be the same thing that happened before, the same things that have been happening for decades and centuries, all the stupid selfish shameful things that we've already seen and have to see again, and it's difficult not to feel apathetic.

That's how everyone reacts to the timequake in the novel, too. Facing ten predictable years, everyone in Timequake decides to just check out mentally. Which is a disaster when the timequake rerun actually ends and free will resumes, because nobody realizes at first that they can control their actions again. They're still zoned out. Which means that cars and planes crash around the world and people start dying, and somebody has to step up and save the world as it awakens.

Vonnegut has a tendency in his novels to write around central cataclysmic events but never show them directly. You never actually see the bombing of Dresden in Slaughterhouse-Five, you hear the birds chirping above the levelled city the morning after. You don't see a neutron bomb hitting Ohio in Deadeye Dick, you hear a group of farmers speculate on who could have dropped it. You don't see the climate collapse in Galapagos, you just survive past the end with a group of tourists in the south Pacific. Rather than watch the disasters, we see what happens after the disaster is over, when it's time to build something new. Similarly, Timequake doesn't spend a ton of time on "the rerun", it focuses more on what happens when free will returns and we can finally stop repeating all of our mistakes.

The only man in Timequake who is able to keep his bearings during the rerun is Kilgore Trout, one of Vonnegut's recurring characters that he often uses as a satirical stand-in for himself. When the cars start crashing and Trout - currently holed up in a Manhattan homeless shelter - realizes that he can make his own decisions again, he knows he has to grab some other people and try to minimize some of the damage. He runs next door and yells at the first person he sees "Wake up! Wake up! You've got free will again, and there's work to do!"

It doesn't work. Nobody knows what he's talking about. So he lands on something else:

"'You've been very sick! Now you're well again. You've been very sick! Now you're well again.'

That mantra worked!

Trout could have been a great advertising man. The same has been said of Jesus Christ. The basis of every great advertisement is a credible promise. Jesus promised better times in an afterlife. Trout was promising the same thing in the here and now."

Trout's neighbor snaps out of it, and Trout realizes he's on to something. He goes back to his shelter and starts telling all of his fellow homeless men "you were sick, but now you're well again, and there's work to do", and after a decade of boredom and regret and being locked in, that is enough to start waking people up and addressing the unfolding global disaster. The men leave the shelter and as it turns out:

"These ragged veterans of unemployability fanned out through the neighborhood to convert more living statues to lives of usefulness, to helping the injured, or at least getting them the hell indoors somewhere before they froze to death."

"You were sick, but now you're well again, and there's work to do," later known as Kilgore's Creed, saves the world, is broadcast across networks to aid in timequake recovery, and becomes the new guiding ethos of society:

"Teachers in public schools across the land, I hear, say Kilgore's Creed to students after the students have recited the Pledge of Allegiance and the Lord's Prayer at the beginning of each school day. Teachers say it seems to help.

A friend told me he was at a wedding where the minister said at the climax of the ceremony: 'You were sick, but now you're well again, and there's work to do. I now pronounce you man and wife.'

Another friend, a biochemist for a cat food company, said she was staying at a hotel in Toronto, Canada, and she asked the front desk to give her a wake-up call in the morning. She answered her phone the next morning, and the operator said, 'You were sick, but now you're well again, and there's work to do.'"

I have personally, as it turns out, found no more concise summary of two thousand years of Catholic theology - the whole thing, original sin, the Paschal mystery, the universal call to holiness, all of it - than "you were sick, but now you're well again, and there's work to do."

On March 27, 2020, I was still pretty sure that we were all going to die; this was very early in the period when the world was still fully shut down. Pope Francis went out into Saint Peter's Square to preside over an "Extraordinary Moment of Prayer" and offer a papal address. If you don't remember what it looked like, there's an image at the top of this piece: Pope Francis spoke in the middle of a massive empty square, in the middle of a massive empty world. And that doesn't ever happen; whenever the Pope is out, he's thronged by thousands and thousands of people trying to get a glimpse of him. This was something different. He said this:

"The storm exposes our vulnerability and uncovers those false and superfluous certainties around which we have constructed our daily schedules, our projects, our habits and priorities. It shows us how we have allowed to become dull and feeble the very things that nourish, sustain and strengthen our lives and our communities. The tempest lays bare all our prepackaged ideas and forgetfulness of what nourishes our people’s souls; all those attempts that anesthetize us with ways of thinking and acting that supposedly “save” us, but instead prove incapable of putting us in touch with our roots and keeping alive the memory of those who have gone before us. We deprive ourselves of the antibodies we need to confront adversity."

We were sick. The world was sick, quite literally. The pandemic alerted us to how we had been sick for a very long time, and made all of our ongoing societal sicknesses much more painful. But:

"You [God] are calling on us to seize this time of trial as a time of choosing. It is not the time of your judgement, but of our judgement: a time to choose what matters and what passes away, a time to separate what is necessary from what is not."

We were sick, but now we have the chance to be well again. I do like the use of "again" in Kilgore's Creed, since it suggests that we were well at some point in the past, that we do know how compassion and solidarity work if we choose to practice them, that we were created to do something good, that we were never hopeless cases. Kilgore Trout and Pope Francis both try to wake us from this crisis of endless repetition, telling us that we were sick, but now we're well again. And Pope Francis also agrees with Trout that there's work to do:

"The Lord asks us and, in the midst of our tempest, invites us to reawaken and put into practice that solidarity and hope capable of giving strength, support and meaning to these hours when everything seems to be floundering...Embracing his cross means finding the courage to embrace all the hardships of the present time, abandoning for a moment our eagerness for power and possessions in order to make room for the creativity that only the Spirit is capable of inspiring. It means finding the courage to create spaces where everyone can recognize that they are called, and to allow new forms of hospitality, fraternity and solidarity."

As appalled as I have been by the Catholic church - mostly the American church - pretty much throughout “these hours where everything seems to be floundering", I can't leave the place that told me that there’s work to do, that the work to be done is the work of solidarity, that it’s the work of realizing the Sermon on the Mount. Losing that is too much. But if I can find such a powerful message in a novel that really spoke to me at the right moment, and I can find that same message in my faith, and if I can lash those two things together, it becomes harder to lose something so big.

There was a moment earlier in Kurt Vonnegut’s life when it felt like the world was maybe going to change for the better. It’s a scene that he presented in fictionalized form in several of his earlier works, and he tells the story of what really happened to him in Timequake. It was shortly after he had, as a POW, survived the bombing of Dresden:

“For a few days after Germany surrendered, on May 7th, 1945, having been directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of maybe forty million people, there was a pocket of anarchy south of Dresden, near the Czech border, which had yet to be occupied and policed by the troops of the Soviet Union. I was in it...Thousands of prisoners of war like myself had been turned loose there, along with death camp survivors with tattooed arms, and lunatics and convicted felons and Gypsies, and who knows what else.”

Vonnegut writes about what happens after the catastrophes, and in his life, that was a moment in 1945, after the world had almost destroyed itself in a war, when thousands of people drawn from all over the world, thousands of wretched and persecuted people who had hungered for righteousness, ended up in the middle of a field wondering what the hell sort of world they lived in now. But they weren’t the only ones there:

“Get this: There were also German troops there, still armed but humbled, and looking for anybody but the Soviet Union to surrender to. My particular war buddy Bernard V. O'Hare and I talked to some of them...we could both hear the Germans saying that America would now have to do what they had been doing, which was to fight the godless Communists.

We replied that we didn't think so. We expected the USSR to try to become more like the USA, with freedom of speech and religion, and fair trials and honestly elected officials, and so on. We, in turn, would try to do what they claimed to be doing, which was to distribute goods and services and opportunities more fairly: ‘From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs.’ That sort of thing.”

Timequake is a novel by an atheist author that is not about Catholicism. But the author had a better understanding of the Sermon on the Mount than most Catholics I know, and the novel itself is a powerful summary of how Catholicism feels to me at the end of this year. Vonnegut lived through a moment where it felt like everything was going to change, and some things certainly did, but a lot of things didn’t. A lot of people just repeated the same mistakes they made before the catastrophe, over and over again, as if they couldn’t stop themselves, as if history itself had been zapped backwards and forced to literally repeat itself. They were still stupid and selfish and shameful, even with the example of the past to look to. And I’ve written about a lot of people in the Catholic church who were stupid and selfish and shameful, even with plenty of examples from Catholicism’s past on why one shouldn’t be stupid and selfish and shameful, and now we’re living in a moment where it feels like everything could change again, or we could end up living through the same mistakes and disappointments over and over.

But at this moment in history, Pope Francis is out in the empty square to tell us that we were sick, but now we're well again, and there's work to do. The work to be done is to live as though we've actually heard and read the Sermon on the Mount. He reminds us thatWwe have to recognize the people in front of us who are poor, sorrowful, meek, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, the merciful, the pure of heart, the peacemakers, and the persecuted. If those people are not in front of us, we should put ourselves in a position where they are. And then, we should treat them as though they are the people that God Himself, our only hope of salvation, publicly declared as blessed above all others. We should suffer with them so they're not alone. We should give them everything they need and fight for them with everything we have. We should be saints to them and with them. We should do everything short of falling down and worshipping them.

At my sister's wedding last month, the priest did not say "You were sick, but now you're well again, and there's work to do. I now pronounce you man and wife," because that doesn't really happen in Catholic weddings. But the priest did do something else: he stood up and he read the Sermon on the Mount. That was the Gospel reading that my sister and her husband wanted to hear before they started their life together, and it was a good choice. Six and a half years ago, my wife and I also wanted to hear that Gospel reading before we started our life together, so another priest stood up at another wedding and read it for us and our families back in 2015. I said I ran into all sorts of reminders of my frustration with the Catholic church at my sister's wedding, but I also ran into this reminder of something that made me feel hopeful.

I needed it. In between my wedding and my sister's, the world got a lot weirder and scarier. A lot of people did the wrong things, and a lot of those wrong things had been done before, and I walked around the back of a church with my daughter a few weeks ago surrounded by reminders of those wrong things, still holding on to my faith by my fingernails, thinking I needed to hold on to it so I could raise my daughter in it, wondering if it was the best idea to raise her in it anyways, and finally thinking that I need to be reminded of the Sermon on the Mount every now and then, to be reminded that there is maybe a way out of this crisis of repetition, and to be reminded that we are sick but we can be well again and that we still have work to do.

In Timequake, Vonnegut writes:

"I got a sappy letter from a woman a while back...She was pregnant, and she wanted to know if it was a mistake to bring an innocent little baby into a world this bad. I replied that what made being alive almost worthwhile for me was the saints I met, people behaving unselfishly and capably. They turned up in the most unexpected places. Perhaps you, dear reader, are or can become a saint for her sweet child to meet.

I believe in original sin. I also believe in original virtue. Look around!"

There are still saints to meet and to be, and there is still so much work to do.

Grift of the Holy Spirit is a series by Tony Ginocchio detailing stories of the weirdest, dumbest, and saddest members of the Catholic church, although admittedly this piece has more of a reflective vibe. You can subscribe via Substack to get notified of future installments. In addition to the sources referenced in the piece, the revised and updated 2016 edition of The Vonnegut Encyclopedia by Marc Leeds was an invaluable help in coordinating quotations across Vonnegut's works.