[a note on content: this piece discusses an alleged campus sexual assault and attempted suicide at length. If you are reading the email version of this piece, it may be truncated for length and you can link to the full piece on Substack by clicking on the title.]

“When I read your speeches, the conclusion one draws is that the dogma lives loudly within you. And that’s of concern when you come to big issues that large numbers of people have fought for years in this country.”

The above words were spoken by Senator Dianne Feinstein during a confirmation hearing for an open seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Feinstein was speaking to (eventually confirmed) nominee Amy Coney Barrett, a law professor at Notre Dame and prolific writer and speaker on the intersection of Catholicism and jurisprudence. Feinstein was expressing - very poorly - her concern about Barrett’s ability to separate Catholic faith from the ability to rule impartially on issues like abortion. I'm generally not a fan of what Feinstein said, or of Feinstein in general; she disagrees with me on the importance of policies like "the Green New Deal" and "not flying the Confederate flag over city hall while you're the mayor of San Francisco". While Barrett is certainly a devout Catholic, it's probably a better line of critique to go after her judicial originalism and unbending far-right ideology, of which there are plenty of examples. Don't say some clumsily worded shit about dogma living loudly, because religious conservatives will use that as a rallying cry and print it on no fewer than two dozen unique coffee mugs at Etsy-like websites:

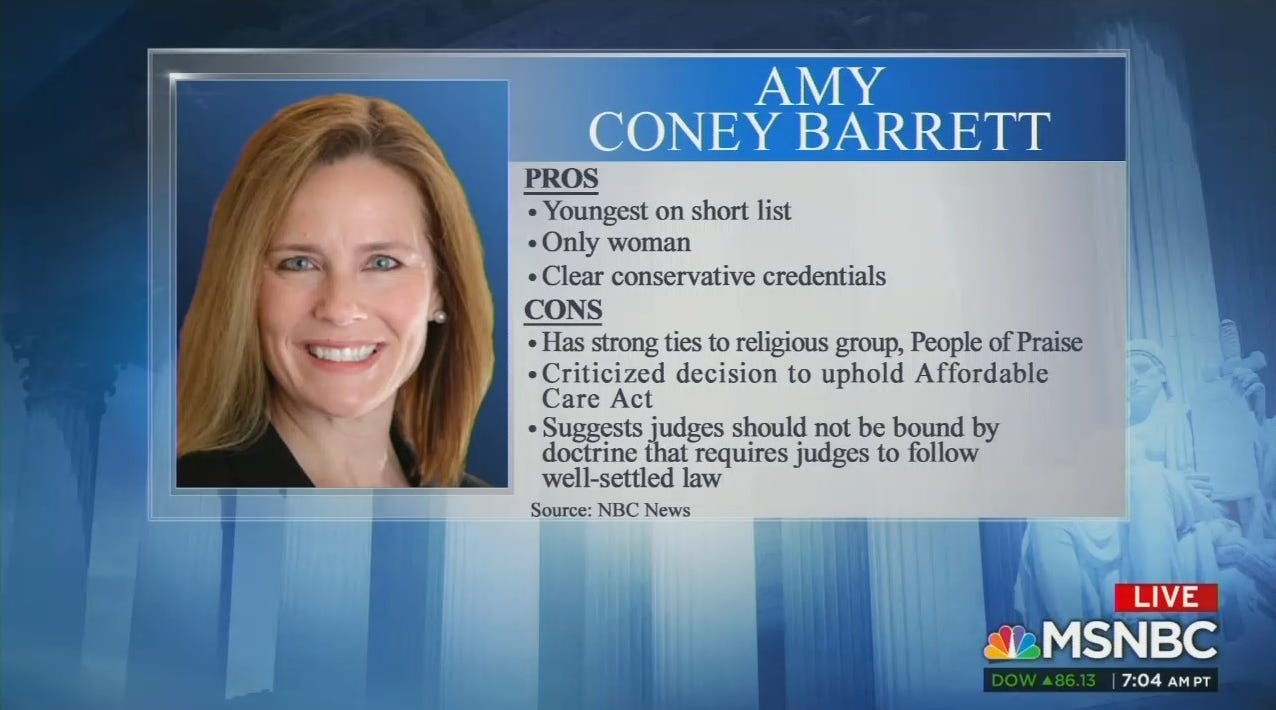

This series of G.O.T.H.S. is about Catholics connected to the Supreme Court, although none of the installments are directly about sitting justices. Barrett is still an appellate court judge (and is still on the faculty at Notre Dame), but she’s more likely than most to be our next Supreme Court justice. She was on Donald Trump’s short list for the seat that was eventually filled by Brett Kavanaugh, and Axios reported in 2019 that Trump was “saving” Barrett to fill Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat if Ginsburg passes away during Trump’s presidency. Even if Trump is not president next year, given that Barrett is a reliable conservative judge and only 48 years old, it’s easy to imagine a future Republican president nominating her to the court in the future. So even if "the dogma lives loudly within you" is a stupid thing to say, we should probably still look into some of Barrett’s most famous articles and opinions to figure out what she considers "dogma" and how she thinks Catholic judges should conduct themselves while remaining faithful to the church.

There was also a little bit of buzz around that “dogma” during Barrett's confirmation to the Seventh Circuit. Barrett comes from a Catholic tradition that we haven't observed yet in G.O.T.H.S.: she's allegedly a member of People of Praise, a close-knit group that arose from the Charismatic Catholic Renewal in the 1970s. I say “allegedly” because People of Praise is very secretive about what they do, and some 2018 reporting characterized them as a cult, but that might be overkill. Still, there is some weird stuff in their history and reported by ex-members, and Barrett refuses to speak about the organization at all, so I understand why an outside observer might worry about her being a cult member.

Now, to be clear, Barrett is absolutely a member of a cult, it's just that People of Praise has nothing to do with that. Barrett is a member of the scariest and most harmful cult of all: the professional pipeline for Republican federal judges.

CHAPTER ONE - PLEASE OPEN YOUR HYMNALS TO NUMBER 289, "DUDES ROCK"

We are definitely going to start with the People of Praise shit, though, are you kidding me? If you read the earlier G.O.T.H.S. on Michael Voris, you'll remember that he attended Notre Dame in the late seventies and early eighties, when the university was basically a laboratory for post-Vatican II innovation in worship and Catholic political engagement. Voris' reaction - and the reaction of other people like him - was to basically pretend Vatican II never happened, or that it was an evil Masonic conspiracy. But a different group in South Bend reacted in completely the opposite direction, started the Charismatic Catholic Renewal, and functionally became overly cheerful Protestants.

That’s not really an exaggeration; members of CCR communities like People of Praise were initially led by Protestants, including Pentacostals, who helped popularize “charisms” like speaking in tongues and faith healing during worship services. People of Praise is not technically a Catholic group, it’s an ecumenical one, which means that all Christians are able to participate (that said, People of Praise skews heavily Catholic, and, because of its history in South Bend, has Notre Dame faculty overrepresented in its membership, and is run by an engineering professor at the university). Compared to a Catholic parish, you would find significantly less emphasis in this community on the traditional Catholic sacraments and hierarchical leadership; since those are, like, the main two things that make the Catholic church the Catholic church, you’re basically just choosing to practice your faith as though you were in a Protestant tradition. In fact, the early leaders of the movement were pretty sure they were going to poach Catholics as a result of organizing these communities, as one ex-member noted:

“The first teachers of the Catholic charismatics were Protestants, especially the Episcopalians and Pentecostals. However, the need for Catholic teaching become clear as the inconsistency of – say – the Pentecostal interpretation of the baptism in the Holy Spirit with the Catholic theology of confirmation became evident. Perhaps even more acute was the problem of direction. Many Protestants, especially the Pentecostals, could not imagine a charismatically renewed Catholic Church, and they fully expected these new Catholic brothers to have to leave their Church. This issue reached a certain watershed in 1973 as the famous Pentecostal evangelist of New York street gangs, David Wilkerson, published his book, The Vision, in which he prophesied that the Pope would reject the Charismatic renewal and “Spirit-filled” Catholics would be forced to leave the Church."

It is hard to overstate how funny it is to me that Episcopalians and Pentecostals tried to run a long con on Catholics looking for a new home after Vatican II, and instead of converting people, just ended up making weirder Catholics. How weird are organizations like People of Praise? Well, let’s see what the New York Times said in 2018:

“Some of the group’s practices would surprise many faithful Catholics. Members of the group swear a lifelong oath of loyalty, called a covenant, to one another, and are assigned and are accountable to a personal adviser, called a “head” for men and a “handmaid” for women. The group teaches that husbands are the heads of their wives and should take authority over the family. Current and former members say that the heads and handmaids give direction on important decisions, including whom to date or marry, where to live, whether to take a job or buy a home, and how to raise children."

Okay, that seems a little unsettling on its face, as well as the requirement that members start by donating five percent of their gross income to the community, and slowly up that to ten percent over time. Slate and National Catholic Reporter had similar reporting at the time, although they also clarified that the organization eventually changed the term “handmaid” to “woman leader” because, well, come on. But the reality is that there are a lot of criticisms of People of Praise for being cult-like and theologically unsound, many of which come from former members, who keep blogs and even organize public Facebook groups where they talk about how wacky charismatic covenant groups are.

The most famous critique is probably from 1997, when former member and Notre Dame philosophy professor Adrian Reimers published Not Reliable Guides: An Analysis of Some Covenant Community Structures. Reimers drew from his own experience as a longtime People of Praise member, stacked the teachings of the group up against the official teachings of the Catholic church, and interviewed other former members of this and other CCR communities to put together a very pointed critique of their governance, structure, and teaching.

Reimers’ criticism of People of Praise is largely theological; his main intent is not to show that People of Praise is some sort of cult, or malfeasant, or abusive towards its members. Rather, he sets out, largely successfully, to show that CCR groups like People of Praise aren’t really doing a good job establishing proper Catholic communities or teaching proper Catholic theology, and seem like they’re trying to supplant the role that a parish is supposed to play in a Catholic community. I would expect that People of Praise would respond by saying that they’re not a Catholic group, they’re an ecumenical one.

But this isn’t some sort of tell-all cult narrative, and I don’t think it would be fair to consider People of Praise anything like a cult, unless they had some sort of systematic commitment to extract money from their members. Or, wait, we already know that they require their members to commit at least five percent of their gross income to the community. Fine, every group can have membership dues, I really don’t think it would be fair to consider People of Praise anything like a cult, unless they were deliberately making it hard for people to leave if they had second thoughts.

“The loyalty or fidelity that the Catholic typically has toward the Church is extended or even transferred to the covenant community....Most decisive is that to leave the covenant community is to leave the most real experience of Christian community one has ever known. But even worse, it is to separate oneself from the body of Christ...In short, to leave a covenant community is emotionally and intellectually far more difficult than to change colleges or careers or to break a wedding engagement. It is more akin to divorce. The departing member knows that he is leaving not just an organization, but an entire way of life. Having invested himself totally in this life, he faces losing it all, and with it the most powerful experiences of religion he may ever have had.”

Ok, well, it’s emotionally difficult to leave People of Praise, fine. But that doesn’t mean that the leadership was deliberately manipulating people into staying against their will.

“When a number of covenanted members left the community as a group in the late 1970s, Kevin Ranaghan gave a teaching attributing their behavior to a specific demon called a “quitting spirit”. By their behavior, these people had manifested their own “quitting spirits”, and this was compared to the attitudes of those who abandon their commitments to marriage and the ordained priesthood.”

Fine, okay, one occasion in the late 1970s, but if that’s all you got-

“On another occasion about three years later, Overall Coordinator Paul DeCelles was explaining the departure from the community covenant by a married couple. The wife had been advised by her doctor that to remain in northern Indiana would seriously endanger her health. DeCelles taught his community that even under such circumstances, the coordinators must be very cautious in releasing members from the covenant. The illness or diagnosis might well be an attack “from the Enemy” to weaken the community…to break the covenant is in some way to be unfaithful to God.”

Okay, well, you’d need at least three instances to make a pattern-

“Another pronouncement appears in the People of Praise internal newsletter, Vine and Branches, May 1992. There Clem Walters (a senior coordinator) affirms that the Overall Coordinator may refuse to release a member from the covenant for that member's own good. The reason is that in the covenant there is seen to be a “spiritual protection” which it is important not to lose. The member – even though he may have chosen to leave the community on the basis of his own free decision – is not regarded as free to leave; to do so is to expose himself to spiritual dangers from which only the community can protect him.”

Okay, as unsettling as all of this is, I’m sure that all of the people in the community live happy lives and don’t have any weird Scientology-like dynamics where they have to confess every bad thought they’ve ever had and are judged by the leadership:

“One can be reasonably sure that any information he gives his head about his own problems or weaknesses will go up the chain to the leadership. Furthermore, no one in the community may ask for or offer confidentiality in the headship relationship, for this would be to create an area of “darkness”, cut off from the light of the Lord."..."It is the capital sin of pride not to reveal all your thoughts and opinions to your head for correction.””

This doesn’t seem to be getting better. Well, there are a lot of married couples, I’m sure those relationships are grea-

“Thus the wife, as a good member of the community, has a prima facie obligation to obey her husband as the bearer of God's will. In practice, this means that the two do not -- indeed, cannot -- relate as equals. His will reveals God's to her, whereas her will is merely human (if not even “of the flesh”). If she becomes angry and argues with him, then she may very well be charged with resisting God's will."

Jesus Christ. Well, as long as they don’t take this to any hilarious extremes-

"An immediate fruit of this is that a kind of wall is built up between men and women in general and between husband and wife in particular. Both communities have developed a clear sense of “men's work” and “women's work”. A man who involved himself in women's concerns or who enjoyed the company of women too much was seen as being “feminized”. The People of Praise even made it a concern to masculinize its song book."

Hell yes, now we’re talking, please open your hymnals to number 289, “Dudes Rock”. Remarkably, although Reimers has plenty of criticism of People of Praise, he rejects the idea that it would be properly called a cult. Perhaps more remarkably, I’m inclined to agree with him; for one thing, People of Praise was only one of two CCR communities he examined in his paper, and the other one, Sword of the Spirit, seems way worse. For another, as strange as this faith tradition seems to me, I understand the desire to live in a close-knit community, I understand how that could arise during the countercultural movement of the 1960s when other non-religious groups were living in communes, I understand the push for greater ecumenism and a de-emphasis on clericalism, and perhaps most importantly, I don’t really think this is weirder than anything else that happens in the Catholic church.

Reimer’s study is from 23 years ago; I would expect at least some things have changed since then, but even if they haven’t, there are grossly outdated gender roles and hustling for donations in mainstream Catholicism as well, we just don’t speak in tongues as much, and we maintain our healthy distrust of Calvinists. Nathan O’Halloran, a Jesuit who grew up in a CCR community, put it this way: “can any healthy Catholic community, religious order or otherwise, claim anything different about its own life? Communities go through growing periods.” People of Praise, I’m sure has had growing pains. So has any Catholic community, or any religious community for that matter, or hell, any commune that started in the 1960s. I feel like Barrett would say the same thing if asked about her experience in People of Praise.

I feel that, but I actually don’t know it for sure, because, as it turns out, Barrett has been asked multiple times about People of Praise, and has refused to comment on it at all. When the New York Times wrote their overview of the group after her confirmation hearing, they reached out to Barrett multiple times for comment, and multiple times, she declined comment through a representative at the Notre Dame Law School. She also did not list any religious affiliations on her Senate questionnaire, although it’s very easy to look up that she was on the board of trustees for a People of Praise high school, which requires trustees to be in People of Praise. So, the dogma may live loudly within her, but I guess not that loudly.

But I can kind of get that, it’s a little bit of a private matter and I would understand if she were reluctant to comment. But, as the Times story also pointed out, People of Praise also went through all of their back issues of their online magazine Vine and Branches and scrubbed out every mention of Barrett’s name that could tie her to the group. So all of this seems a little off. It’s possible that People of Praise is perfectly innocuous today, if a little weird-looking. But it’s not really clear why they’re trying so hard to keep things so secret.

I would have even accepted Barrett saying “yeah, I’m in People of Praise, but it’s not like I’m spending all of my time there because my entire career has always been oriented towards hustling for a seat on the Supreme Court”; I know that the second half of that, at least, is true. There’s absolutely a career path to get on the Supreme Court, and Barrett has followed it very closely. She went to a ranked law school and graduated Summa Cum Laude and Phi Beta Kappa. While in law school, she edited the Law Review, and herself is a prolific writer on many legal issues. She clerked for a federal judge and a Supreme Court justice, and then she worked for a boutique firm for power players in DC before returning to academia. Now she’s a judge and on the Supreme Court shortlist. But how does someone like her view the role of a judge, especially if that judge is someone with her faith background? How should a judge who is also a devout Catholic conduct herself? There is also some legal and theological research on this topic, and a good place to start would be a law review paper from 1998, co-authored by a fresh-faced law school graduate named Amy Coney Barrett.

CHAPTER TWO - THIS IS SOMETHING THAT ASSHOLES SAY

Barrett’s 1998 paper for the Marquette Law Review, “Catholic Judges and Capital Cases”, is notable because it’s more a work of Catholic moral theology than a review of dense case law or judicial opinions. Of course, Catholic moral theology is one of the few academic fields somehow more dense than the law, but Barrett treks through various encyclicals and other church teachings to explore the question of how a devout Catholic judge, one who views execution by the state as intrinsically evil, should handle criminal cases where it’s possible that the defendant could receive a death sentence.

Key to Barrett’s paper are two terms in moral theology, which I think will be important later in understanding her career goals. The two terms are formal cooperation with evil and material cooperation with evil. Formal cooperation with evil is the simpler one: it’s when you are directly responsible for a bad thing, knowing that it’s bad. Material cooperation has a higher number of gray areas: it’s when you’re indirectly involved in the bad thing being done, but not the main person committing the act, and because of that, it’s possible that someone materially cooperating with evil is not actually morally culpable for the evil being done.

Here’s how I had it explained to me in an undergrad theology class, discussing the abortion debate: If you’re a doctor who terminates a pregnancy, an observant Catholic would probably say that you are formally cooperating with evil, that you are knowingly doing an evil thing and taking a life. If you’re the person at the front desk of the clinic who files the paperwork for the procedure and bills insurance, well yes, you’re still participating in the act on some level, but clearly you don’t have the same level of involvement as the person formally committing the evil act. And if it’s your job to file paperwork for all sorts of medical procedures anyway, then it’s hard to say that you are someone who woke up and decided to do an evil thing, so much as you are a person out there doing your job for the day and not giving it a second thought. You’d be materially cooperating with evil, but not considered morally responsible for what happens.

So Barrett takes these concepts to a state execution: the executioner who flips the switch would be formally cooperating with evil, and the logistics director at the pharma company who makes sure the potassium chloride shows up at the prison is likely more of a material cooperator. But what about the judge who sentences a defendant to death? What if that judge is bound by a jury verdict? Here's where Barrett landed:

"We believe that Catholic judges (if they are faithful to the teaching of their church) are morally precluded from enforcing the death penalty. This means that they can neither themselves sentence criminals to death nor enforce jury recommendations of death. Whether they may affirm lower court orders of either kind is a question we have the most difficulty in resolving.”

So, interestingly, Barrett does identify that judges should recuse themselves in death penalty cases, and she considers even enforcing a jury verdict to be a formal cooperation with evil. Which means she identified, early in her career, a case where a devout Catholic judge should be recusing herself so as not to participate in something evil.

There are some important qualifications here: first, her rule does not apply to any appellate judges, as Barrett doesn’t consider them to be formally handing down a death sentence, but rather assessing the earlier trial procedure, and thus materially cooperating with the execution at the most. This strikes me as splitting too many hairs, since an appellate judge can essentially prevent a man from being executed, and I would think that choosing not to do so would also be a pretty clear moral choice. But for Barrett, there’s apparently a real danger of Catholic judges going rogue and saving too many lives?

“Robert Cover once argued that the judge has a moral obligation to engage in just this sort of nit-picking to save as many lives as he can. This is a suggestion that we reject. There is a real moral cost to undermining the legal system, even in small ways. If the systemwere completely corrupt (as, say, the regime in Nazi Germany was) we could ignore this consideration. But it is hardly possible to make that claim about our own legal system. It has flaws-the death penalty is one. On the whole, though, it is a decent and just institution that judges should take care to preserve. If one cannot in conscience affirm a death sentence the proper response is to recuse oneself. If the judge does no moral wrong in affirming, he should enforce the law in easy cases, even if he could save a life by cheating.”

For Barrett, it’s precisely because appellate judges are not formally cooperating with executions that they shouldn’t feel bad about upholding existing death sentences - and, also, to not rock the boat too much. What starts as an interesting moral argument starts to creep more into something sounding like an excuse for Catholics to feel okay about the death penalty. In fact, it starts to feel downright icky to read about the appropriate way to assess an appellate judge's cooperation with evil when a man is about to be executed and a more relevant question might be "who has the power to change something here, and will they?" Barrett does not reassure me when she goes on to make the same arguments that conservative Catholics have used for years as they’ve voted Republican: the church's death penalty teaching is not super-important.

"In modern Catholic teaching, capital punishment is often condemned along with other practices whose point is the taking of life-abortion, euthanasia, nuclear war, and murder itself. It is sometimes said that consistency requires no less-that respect for life in all these cases is a seamless garment. Human beings are created in the image and likeness of God, and "[h]uman life is thus given a sacred and inviolable character, which reflects the inviolability of the Creator himself." 'That seems to make things pretty simple. It is a good rule of thumb to say, "No killing. Period." But...the prohibitions against abortion and euthanasia (properly defined) are absolute; those against war and capital punishment are not...Moreover, it cannot fairly be said that the current teaching [on the death penalty] has been the unanimous and long-standing belief of the church."

This is something that assholes say; being "pro-life" only means caring about the life issues that line up neatly with the GOP platform (for example, some Catholics over at First Things don't think "pro-life" applies to trying to flatten a pandemic curve). To say that the church teaching on the death penalty has not been unanimous or consistent is correct, but it would also be correct about abortion, where you can find debates between medieval theologians about when "ensoulment" of an embryo occurred, and certainly correct about the level of emphasis that abortion should receive in our hierarchy of moral issues. To paraphrase an old joke, if a Catholic begins a sentence with "as the church has always taught", they're about to spew some bullshit. Barrett even points out that when the USCCB voted to strengthen their teachings on the immorality of the death penalty, because the vote was not unanimous, and because a lot of Americans think the death penalty is good anyways, the USCCB teaching is actually not something we need to take as seriously as other church teachings. One wonders if she would feel the same way if Americans were in favor of abortion access or using artificial contraception. I'm kidding, I don't wonder about this, I have a very good guess.

Barrett got asked about this particular paper a lot during her confirmation hearing, as Democratic senators thought it hinted at her views on abortion (which it kind of did) and at a belief that she should recuse herself from capital cases as an appellate judge (which it kind of didn't). Barrett was smart enough to deflect or redirect these questions, and eventually, in response to Mazie Hirono, wrote "I have not thought in any serious way about the conflicts between conscience and judicial duty in twenty years, since I was a third-year law student working on this article with a senior professor. Like any judge or judicial nominee, I cannot say how I might resolve any issue that might come before me as a judge."

The second sentence is the same sort of deflection that any judicial nominee would do, and I strongly doubt that a Notre Dame law professor who wants to be on the Supreme Court would go two decades without thinking about conscience and judges at the same time. But I certainly don't disagree that the paper is very old, and it would be reasonable to expect her to think differently after twenty years working in law. Barrett published this paper immediately out of law school, and went on to clerk, including at the Supreme Court, and of course, she clerked for the grandaddy of today's conservative jurisprudence, Antonin Scalia.

You probably remember that when Scalia died in 2016, he was basically canonized by the political right, but plenty on the political left also fondly remembered his contributions to the legal world. As one of the first high-profile proponents of “originalism” and "textualism" - the idea that the Constitution and federal law was best interpreted through the literal text and original intent of the writers of the Constitution, putting aside things like legislative intent or historical context - Scalia was remembered, even by his political opponents, as a brilliant and innovative legal mind, as well as a memorable and razor-sharp wit. Everyone who said these things was incorrect. Scalia sucks, originalism sucks, and most importantly, Barrett sucks for liking Scalia and originalism. Let’s take a moment to understand why.

CHAPTER THREE - THE ETERNAL BANGER

To be clear, Barrett does very much like Scalia and originalism, and we know this from her 2017 Notre Dame Law Review article, "Originalism and Stare Decisis", where Barrett reviewed her former mentor's Supreme Court opinions and examined how he, in Barrett's opinion, brilliantly balanced these two seemingly opposed poles. Since the final sentence of the article is literally "Nothing is flawless, but I, for one, find it impossible to say that Justice Scalia did his job badly", we're going to sneak a quick review of Scalia's greatest hits into the center of this essay, much like the bread crumbs and raisins in the delicious flank steak bracioles that clogged Scalia's arteries and led to his unexpected demise.

Stare decisis, in this context, is the idea that the Supreme Court should be very reluctant to overturn its own precedent, that there needs to be consistency in what the Court decides, even if the justices turn over. When judicial appointees are asked about stare decisis - as Barrett was, multiple times in her confirmation hearing - they’re usually being asked in a roundabout way about abortion, and whether they’d be willing to overturn precedents like Roe and Casey. Nobody in the Senate asks these questions directly, and no appointees answer these questions directly, but the questions and answers are definitely there.

In Barrett’s article, she praises Scalia for being willing to overturn Supreme Court precedent all the time, and finding a way to balance that with his originalist approach to constitutional law. As she put it:

“Justice Scalia framed some of his most vociferous disagreements with Supreme Court precedent as a defense of a competing form of precedent: the history and traditions of the American people...he argued...that Miranda v. Arizona should be discarded for its lack of support in “history, precedent, or common sense.” He was persistent in his view that “the Double Jeopardy Clause prohibits successive prosecution, not successive punishment,” and...he repeatedly argued that the Court should overrule its cases holding that a woman has a substantive due process right to terminate her pregnancy.”

I’m not entirely sure that either Scalia or Barrett should be bragging about fighting against Miranda rights, or getting around double jeopardy to punish defendants multiple times. But, according to Barrett, Scalia respected the precedents and opinions that really mattered, as "Justice Scalia was never forced to make any of the decisions that critics cast as deal-breakers for originalism. He was never required, for example, to decide whether paper money is constitutional or whether Brown v. Board of Education was rightly decided." Personally, I am very grateful that Scalia was never in a position to weigh in on whether Brown v. Board was rightly decided.

What’s very striking, though, is that Barrett left out a lot of Scalia’s most infamous decisions, the ones where he ignored both precedent and originalism to just advocate for the most horrible outcome possible. In 2005’s Castle Rock v. Gonzales, Scalia ignored the literal, textual meaning of a Colorado state law explicitly worded and passed to mandate that police enforce restraining orders, essentially telling a woman who had her three children murdered by her ex-husband to fuck off. In 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges, his dissent argued that states should be able to ban gay marriage because states have a long and proud history of discriminating against gay people (the opening line of that dissent is the eternal banger “I join The Chief Justice’s opinion in full. I write separately to call attention to this Court’s threat to American democracy”). The originalist interpretation of the Second Amendment does not guarantee an unrestricted right to individual handgun or semiautomatic weapon ownership, because there weren’t handguns or semiautomatic weapons when the Second Amendment was written and the explicit text of the amendment regard militia membership, but Scalia found a way to make it all work in 2008’s DC v. Heller, overturning centuries of jurisprudence on guns. In his dissent in 1992’s Planned Parenthood v. Casey, he straight-up said that Roe should be overturned because abortion was clearly immoral and stare decisis didn’t matter. His dissent in 1992’s Lawrence v. Texas, the case which struck down anti-sodomy laws, is basically one giant homophobic rant in which Scalia also speaks directly to how he views the importance of stare decisis, but Barrett decides not to touch it, possibly because if you want to write a paper on how great Scalia is, you really can’t include anything from that particular opinion where he compares gay sex to heroin addiction.

Barrett’s paper doesn’t touch any of these greatest hits, but it manages to go somewhere very dark indeed when she gets into Eighth Amendment opinions, regarding cruel and unusual punishment:

“Justice Scalia thought that the Court’s Eighth Amendment cases were flawed in at least two respects. First, he thought that the Court should look to the original application of the Eighth Amendment, not evolving standards of decency, to determine whether a punishment was “cruel and unusual.” Second, he rejected the proposition that the Eighth Amendment requires that a punishment be proportionate to the offense.”

I had to reread this passage several times to make sure I understood it correctly, because it sure looked like Barrett was praising Scalia for not being a pussy and accounting for human decency when it came to cruel and unusual punishment, or proportionality of a punishment overall. Then I finally checked Barrett’s footnote to this sentence, which praised Scalia for 1989’s Stanford v. Kentucky decision where he was apparently principled enough to uphold the death penalty for minors and reject that these executions would violate the Eighth Amendment (the Court would overturn this decision just two years later). Remember, twenty years ago, Barrett wrote a paper saying that observant Catholic judges - a group in which Scalia would have certainly included himself - should recuse themselves in death penalty cases. Scalia wasn’t technically sentencing someone to death in this case, but this is a man who can opine on the morality of abortion from the bench and make it clear that he would change abortion laws if he could, and he was ready to enforce the death penalty for minors, and to Barrett two decades later, this was a brilliant balancing act between originalism and the will of the American people.

Scalia’s originalism, in practice, appears to mean “doing whatever the leadership of the Republican party wants me to, or barring that, whatever will cause the most pain to the people who are not in power”. His philosophy is not any remarkable feat of analysis, but it is key to Barrett’s judicial philosophy. She’s a member of the Federalist Society, the horrifying pipeline of conservative judges to which Trump has basically outsourced all of his judicial picks, and which has originalism as a cornerstone of their philosophy. To be fair to Barrett, she only paid dues to the Federalist Society from 2005-2006 and 2015-2017, which means she was only a member during times when she was reasonably certain that there’d be a Republican president in office and vacancies coming in federal courts. I very much admire her thrift.

How does a judicial philosophy like this jive with Catholicism overall? Bishops have often taught that Catholic teaching does not align neatly with either major American political party, but there sure seem to be a lot of Catholic judges that can follow the Republican party line pretty well. If judges, and Supreme Court justices, can cite their own consciences and sense of morality when talking about abortion or the death penalty, why aren’t they doing the same thing for immigration or preferential treatment of the poor? Because that’s not what the job is, if you want a Republican president to put you on the bench. Michael Sean Winters, writing for National Catholic Reporter, contended that “Scalia's theory has not even a passing similarity with our Catholic intellectual traditions...Catholic intellectual life understands that our moral life, even our moral absolutes, exist in time, not beyond it. Scalia's approach pretended to deny that most obvious of human realities.” Dunking on Scalia at any point rules, dunking on him in a Catholic publication after his death also rules. Winters went further with it, though, when discussing Barrett as the possible replacement for Anthony Kennedy on the Supreme Court in 2018:

“The conservative Catholic legal establishment is largely responsible for this singular focus on neuralgic sexual issues (with the recent addition of an almost paranoid fear about religious liberty), an establishment that was only too willing to view this deformation of the church's public witness as necessary collateral damage in their quest to align their religion with their politics. Barrett is not responsible for this deformation of the Church's public witness but she is a product of, and has been groomed by, the conservative Catholic legal establishment that is responsible. She is part of it and, having been groomed, is now the face of that establishment. Just so, I hope she is not nominated and if nominated that she is not confirmed.”

The problem is not Barrett’s People of Praise membership, or her Catholicism at all, it’s the political machine that takes Catholics and turns them into awful reactionary judges. She knew about the machine and threw herself into it; this paper about Scalia was published shortly after the election of a president who campaigned on filling Scalia's seat with a judge like Scalia. She had recently resumed paying dues to the Federalist Society. She was doing work to get on the federal bench. I don't know what she said to Trump when she was nominated, but I doubt it was “aw shucks how did you find me?”

All of that said, though, we’ve talked a lot about Barrett’s possible judicial philosophy and the judge she learned the most from, but she’s been a judge herself for less than three years. Do we really think, in so short a period of time, that there would have already been a case before her that was so maddeningly absurd, on a timely hot-button issue, that it could clear the high bar of absurdity that I try to maintain here on G.O.T.H.S.? Yes. Of course. Absolutely. How could there not be.

CHAPTER FOUR - MOTION TO AFFIRM THAT DUDES ROCK

Doe v. Purdue University is a 2019 case involving a campus sexual assault, and as you would expect, the case is full of complexities and infuriating contradictions. As the title of this chapter suggests, the plaintiff and legal system, up through the honorable Judge Barrett of the Seventh Circuit, treated this case with all of the gravitas it deserved.

The plantiff is a former undergrad at Purdue referred to as John Doe, who was dating a woman while a student at the university, referred to as Jane. Jane alleges that Doe sexually assaulted her, and after their relationship ended, she attempted to take her own life, which Doe witnessed and reported to the university. After attending a campus sexual assault awareness event long after this relationship ended, Jane reported her assault and Doe was suspended from the university after being found guilty in a disciplinary hearing.

Doe sued the university in federal court, claiming that the hearing was essentially a sham and revenge for reporting Jane’s attempted suicide, but the district court dismissed basically all of his claims. Some of the dismissals were based on technicalities - Doe didn't have the right standing to sue in some cases, and some of the university officials named as defendants weren't close enough to the disciplinary hearing to get sued. But Doe had two specific claims that were especially eye-catching.

First, Doe claimed that his Fourteenth Amendment rights had been violated - you know, the amendment that made former slaves into citizens during Reconstruction. The amendment also prevents citizens from having the government take their life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. According to Doe, the university hearing didn't satisfy due process - he wasn't allowed to call witnesses, have an attorney represent him, the things you would expect in an actual criminal trial. The court dismissed this since Purdue wasn’t a government actor, Doe made no effort to re-apply to Purdue, and university disciplinary hearings, by design and formally under Title IX law, are not criminal trials. Doe’s claim also didn’t square with existing case law in this area.

But the second, and more important, claim from Doe was that dudes rock. See, Doe also said his own Title IX rights had been violated, because Purdue's methods for handling sexual assault accusations were inherently biased against men, given that men were disciplined for sexual assault more often than women. I hate to write this twice in the same piece, but: this is a thing that assholes say. Title IX is the reason why universities have tried to step up in the past decade to investigate sexual assault and do more for victims, because not doing so, under guidelines issued by the Obama administration in 2011, would amount to a civil rights violation on the basis of gender. Universities were specifically directed to use lower standards of evidence than criminal trials for these hearings, because they weren't criminal trials and universities needed to err on the side of believing victims to best protect their students. Doe asserted that the true victims of this policy were the men, who just wanted to fingerblast coeds on filthy futons without fear of being extrajudicially expelled.

As you probably have guessed, this is not how Title IX is actually supposed to work. Both Doe's due process claim, as well as his dude process claim - which is like due process but only for the fellas - were dismissed, with prejudice, by the district court, who wrote:

"Plaintiff attempts to demonstrate a pattern of gender bias by alleging that the totality of the circumstances establishes that Purdue has "demonstrated a patter of inherent and systematic gender bias and discrimination against male students accused of misconduct." Plaintiff alleges that, "on information and belief," "all students that have been suspended or expelled from Defendant Purdue for sexual misconduct have been male." And, "[m]ale respondents, and particularly male athletes and male ROTC members, in sexual misconduct cases at Defendant Purdue are discriminated against solely on the basis of sex. They are invariably found guilty, regardless of the evidence, or lack thereof." None of these allegations offer statistics or facts to support a pattern of gender discrimination; again, even if all the respondents were male and all were punished, without more, this only alleges victim bias, and not gender bias."

And victim bias is supposed to be part of the investigative process, because if you don’t build it in there, it becomes incredibly easy for universities and accused assaulters to game the system to keep assaults under wraps (as a side note, my favorite book on this topic is Jon Krakauer’s Missoula, which details multiple cases at the University of Montana, where the school made every effort to protect the players of its championship-winning football team during a rash of sexual assault cases. Purdue was obviously in a different situation here as their football team has always been trash, but the overall lesson holds). Doe wasn't thrilled with the result, so he appealed, and his case landed in the Seventh Circuit, and Barrett wrote the opinion. You will never guess how the woman from the rigidly hierarchical People of Praise, the woman who idolized Antonin Scalia, and the woman actively auditioning to be Donald Trump’s next Supreme Court pick, feels about whether dudes rock.

Barrett reversed the district court's dismissal in both the due process and Title IX claims, and the case has been remanded back to the district court, who now has to hear Doe out. The due process argument is complex, but came down to the fact that in being suspended from the university, Doe also lost his scholarship through Navy ROTC and was not able to pursue “a protected liberty interest: his freedom to pursue naval service, his occupation of choice”. I don’t necessarily agree with the decision, but I can understand the reasoning here, as a ROTC scholarship does have a monetary value and is given by a government actor, so it is possible that Doe lost something without appropriate due process.

Barrett’s opinion on the Title IX claim, however, is...very bad. According to her, the hearing did not do enough to investigate whether the victim of the alleged assault was just one of these dumb bitches who probably isn’t right in the head. From her opinion:

"[Purdue’s Dean of Students] Sermersheim and the Advisory Committee’s failure to make any attempt to examine Jane’s credibility is all the more troubling because John identified specific impeachment evidence. He said that Jane was depressed, had attempted suicide, and was angry at him for reporting the attempt...And John insisted that Jane’s behavior after the alleged assault—including her texts, gifts, and continued romantic relationship with him—was inconsistent with her claim that he had committed sexual violence against her."

Yeah, come on, she’s depressed, her behavior is inconsistent, the assault was at the hands of someone she knew and already had a relationship with, these definitely aren’t things that are common in sexual assault victims, right? It’s not precisely because the legal system will dismiss victims, for these exact reasons, that sexual assault is so hard to prosecute and investigate, right? Sadly, Barrett did not include any speculation as to what Jane was wearing at the time of the alleged assault, but she did wonder why Jane didn’t bother to relive her assault directly as part of the disciplinary process:

“The case against [Doe] boiled down to a “he said/she said”—Purdue had to decide whether to believe John or Jane. Sermersheim’s explanation for her decision (offered only after her supervisor required her to give a reason) was a cursory statement that she found Jane credible and John not credible. Her basis for believing Jane is perplexing, given that she never talked to Jane. Indeed, Jane did not even submit a statement in her own words to the Advisory Committee. Her side of the story was relayed in a letter submitted by Bloom, a Title IX coordinator and the director of CARE [Purdue’s Center for Advocacy, Response, and Education].”

Yeah, why would Jane submit her statement through the Title IX coordinator, when the 2011 guidance from the Department of Education explicitly set up measures like these so that a victim and alleged perpetrator wouldn’t have to confront each other directly? Barrett is, at best, being incredibly ignorant here. The reasons that she lists for reversing the district court’s judgment are the exact reasons that there was an epidemic of campus sexual assaults to begin with: students didn’t have a place to go to report assaults knowing that there would be followups, victims’ trauma was used to discredit their stories, and too many people waved these assaults off as “he said/she said” cases. But Barrett - who was and is still employed by a university that also had to strengthen its Title IX procedures in the 2010s and was the subject of national news and a goddamn Oscar-nominated documentary, with an original song by Lady Gaga, precisely because of how shitty they were at handling sexual assault cases - doesn’t seem to be aware of any of this. The main thing she’s aware of is this:

"It is plausible that Sermersheim and her advisors chose to believe Jane because she is a woman and to disbelieve [Plaintiff] because he is a man. The plausibility of that inference is strengthened by a post that CARE put up on its Facebook page during the same month that Doe was disciplined: an article from The Washington Post titled “Alcohol isn’t the cause of campus sexual assault. Men are.” Construing reasonable inferences in Doe’s favor, this statement, which CARE advertised to the campus community, could be understood to blame men as a class for the problem of campus sexual assault rather than the individuals who commit sexual assault."

The gist of that Post article is that policy solutions for campus sexual assault should include more bystander training, as tighter alcohol policy isn’t going to do enough to stop people from being assaulted. It’s literally in the subheadline of the article - I didn't even need to log in with a WaPo account to get to that! - but I’m not even sure Barrett Googled it or just saw the headline and said “Are they saying that dudes don’t rock? No, we need to quash this right away.”

Barrett really, really wants to be on the Supreme Court, which means that in order to advance in her career, she needs to, above all, be the kind of person that Donald Trump considers impressive. So she wrote about how she could uphold death sentences as a Catholic, she wrote about how great Antonin Scalia was, she paid dues to the Federalist Society, and with Doe v. Purdue, she had the chance to shit on a well-known Obama-era regulation and strike a blow for these men who are being treated very unfairly, so unfairly, when they assault women, people are saying it more and more. Congratulations to her for getting one step closer to a seat on the court.

EPILOGUE

There’s a reason I titled this piece “Amy Coney Barrett, Future 6-3 Vote” and not “Amy Coney Barrett, Person of Praise”. The most horrifying thing about her is not People of Praise, it’s not the moral knots she tied around capital punishment, it’s not her praise of Scalia, it’s not her awful decision in Doe v. Purdue. It’s that all of those things are just checking boxes to impress Donald Trump and eventually get on the Roberts Court.

And even if I only limit myself to decisions the Roberts Court has made since Trump has become president, I can find decisions that range from infuriating to truly evil. In Janus v. AFSCME, the Court gutted the power of public sector unions, in a case where the U.S. bishops actually wrote an amicus brief asking the Court to rule the other way. In RNC V. DNC 2020, the Court threw out thousands of absentee ballots in Wisconsin, forcing primary voters to go and vote in a pandemic during a shelter-in-place order if they wanted their vote counted (at the time of this writing, around fifty new COVID cases had been traced to this specific election). Perhaps their most egregious decision has been Trump v. Hawaii, which upheld the Muslim immigration ban, and signalled that this court would be as deferent to the president as possible as he carried out his racist and inhumane policies. Barrett has seen all of this and said “I want to be a part of this, please, Mr. Trump.” That’s bad enough, even if I put aside gutting the Voting Rights Act or allowing unlimited campaign donations or arresting the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

The moral question that I want to ask, one more time, is “who has the power to change something here, and will they?” These nine justices have the power to change things in this stupid broken country, more power than pretty much anyone else, and instead they choose to break the country further. Barrett is volunteering herself to continue this tradition, and demonstrating in decisions like Doe that she’s fully on board with what’s currently happening. Since this is a series about Catholicism, I’ll put it in moral theology terms: Amy Coney Barrett, in her current job, materially cooperates with the evil being done by the Roberts Court and Trump administration. But she apparently aspires to formally cooperate with that evil.

Grift of the Holy Spirit is a series by Tony Ginocchio detailing stories of the weirdest, dumbest, and saddest members of the Catholic church. You can subscribe via Substack to get notified of future installments. The current series covers Catholics connected to the United States Supreme Court.

Sources used for this piece include:

SCOTUSBlog - “Potential Nominee Profile: Amy Coney Barrett” (2018)

Axios - “Trump ‘Saving’ Judge Amy Barrett for Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Seat” (2019)

Notre Dame Magazine - “Students, Faculty Mark 40 Years of Roe” (2013)

People of Praise - “Who We Are” (2020)

Slate - “Amy Coney Barrett Is Allegedly A Member Of…” (2018)

New York Times - “Some Worry About Judicial Nominee’s Ties to a Religious Group” (2017)

Adrian Reimers - “Not Reliable Guides: An Analysis of Some Covenant Community Structures” (1997)

National Catholic Reporter - "Prospective Supreme Court Nominee Puts Spotlight on People of Praise" (2018)

National Catholic Reporter - "Raising Questions About Amy Barrett's Beliefs Is Not An Anti-Popery Riot" (2018)

America Magazine - “I Grew Up In A Charismatic…” (2018)

Marquette Law Review - “Catholic Judges in Capital Cases” (1998, archived at Notre Dame’s website)

Senate Judiciary Committee - "Amy Coney Barrett, questions for record" (2017)

Notre Dame Law Review - “Originalism and Stare Decisis” (2017)

Mic Dicta - “Episode 7: Tony Story” (2018)

5-4 Podcast - “Episode 9: Castle Rock v. Gonzales” (2020)

United States Supreme Court - "City of Chicago v. Morales et al, no. 97-1121" (1999)

United States District Court - "Doe v. Purdue University" (2019)

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit - “Doe v. Purdue University” (2019)